#873 A castle for all Victorians

Craigdarroch: The Story of Dunsmuir Castle

by Terry Reksten

Victoria: Orca Books, 2019 (first published by Orca Books, 1987; reprinted 1994, 1997, and 2000)

$16.95 / 9781459823846

Reviewed by Matthew Downey

*

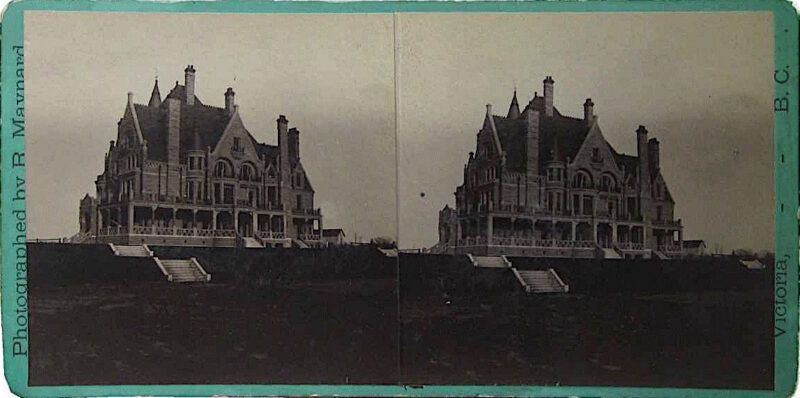

This new printing of the late Terry Reksten’s Craigdarroch: The Story of Dunsmuir Castle provides to a new generation of readers a short yet sweeping history of arguably the most identifiable landmark in Victoria. Reksten (1942-2001) relays Craigdarroch’s broad story concisely, from its construction by coal-baron Robert Dunsmuir as an expensive and ostentatious allusion to the ancient heritage of his Scottish homeland, to the mansion’s modern role as a cultural icon that impresses tourists from all over the world. Besides the amount of ground covered by such a short book, the most impressive aspect is the frank way in which Reksten confronts the decidedly unromantic and institutional phases of the castle’s past since its completion in 1890.

This new printing of the late Terry Reksten’s Craigdarroch: The Story of Dunsmuir Castle provides to a new generation of readers a short yet sweeping history of arguably the most identifiable landmark in Victoria. Reksten (1942-2001) relays Craigdarroch’s broad story concisely, from its construction by coal-baron Robert Dunsmuir as an expensive and ostentatious allusion to the ancient heritage of his Scottish homeland, to the mansion’s modern role as a cultural icon that impresses tourists from all over the world. Besides the amount of ground covered by such a short book, the most impressive aspect is the frank way in which Reksten confronts the decidedly unromantic and institutional phases of the castle’s past since its completion in 1890.

By reconciling the castle’s fantastical image with its practical uses as a military hospital, a college, and an office building, Craigdarroch portrays an important truth about cultural monuments more generally: very often they are not as romantic as they are presented. Reksten acknowledges the seemingly arbitrary nature of Craigdarroch’s landmark status: this castle has no innate centrality, and no transcendent cultural or political role, in Victoria similar to the Provincial Parliament buildings, Government House, or even the Empress Hotel. Yet any yearning for romance from outside visitors to Victoria — apparently a historical outpost of British class-culture — is bound to drive them to the looming castle towers that are easily viewed from downtown. The same fascination that leads tourists to bus up the rugged Saanich Peninsula to walk the cultivated pathways of the Butchart Gardens draws them to file down the halls of Craigdarroch, the archaic and mysterious home of BC’s fin de siècle home-grown industrial aristocracy.

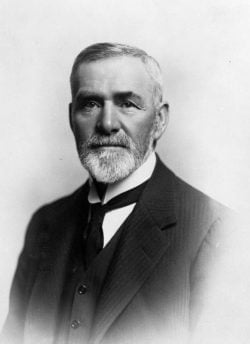

While Craigdarroch is not focused expressly on Robert Dunsmuir or his family, Reksten necessarily provides a summary of their role in British Columbia’s history. An ostensibly controversial (p. 32) yet impressive rags-to-riches colonial success story, Robert came to dominate the Vancouver Island coal industry after having arrived in 1851 as an “oversman” to the Hudson’s Bay Company’s colliers at Nanaimo (p. 7). Reksten introduces the intricate character of Dunsmuir and his family, brushing over moments of controversy concerning working conditions and strike-suppression as well as achievements such as the construction of the E&N railway that connected Dunsmuir’s Nanaimo mines with the Royal Navy’s coaling station at Esquimalt (p. 33). His desire to emulate the displays of wealth in San Francisco’s Nob Hill mansions inspired him to construct the hilltop castle that still dominates the Victoria landscape (p. 20).

After Robert’s death in 1889, the remainder of the castle’s construction was taken up begrudgingly by his widow Joan and sons James and Alex (p. 37). Reksten shows how the real romance connected to Craigdarroch ended with Robert Dunsmuir’s death. The Dunsmuir family continued its empowering influence through James Dunsmuir’s work as provincial premier and then lieutenant-governor, but the family then engaged in infighting and drama arising from discrepancies in the wills left by Robert, and then by his son Alex on his death in 1900 (p. 52). Craigdarroch, once finished, simply became the home of a grieving and angry widow (p. 56).

Upon Joan Dunsmuir’s death in 1908, most of the castle’s surrounding estate was subdivided and sold off in a strange lottery scheme (p. 59). As Reksten explains, the castle was so hard to sell that it became the prize in a draw devised by the family’s real estate agent: anybody who bought one of the subdivided lots, which were subsequently divvied out by chance, was entered into the draw (p. 60). In an ironic twist, the man who ended up being awarded the castle property could not afford the substantial cost of living in it, and Craigdarroch was taken over by the bank (p. 62).

Thus began Craigdarroch’s considerable time as a purely practical building, leased out and converted into a ward for injured veterans of the First World War (p. 63), turned into a barely-functional campus for the burgeoning Victoria College (p. 88) – where, among others, historian Pierre Berton was a student from 1937-39 — and afterwards converted into an office headquarters for the Victoria School Board (p. 94). It was not until eccentric Victoria journalist and popular historian James Nesbitt took an interest in preserving the castle for expressly cultural purposes that the site was pushed along the way to becoming a landmark (p. 98). Even as the building was used as an office space, Nesbitt encouraged visitors to the castle and, by his own initiative, stood by the entrance to collect donations (p. 101).

Reksten effectively covers Craigdarroch’s different roles in just enough detail to introduce the reader to a comfortable level of the benign aspects of each era while not lingering for long on any. For instance, she relishes in the jovial war-games played during the castle’s college years (p. 77), the details of which are unimportant beyond the pseudo-dramas of student life (p. 81); but by engaging with them, Reksten reveals the real life of Craigdarroch in all its unremarkable truth. Her extensive use of photos gives visual life to moments both mundane and glamourous. In truth, the High Victorian splendour of the halls and rooms of the castle would signify for some nothing more than a ward or a classroom. The impression of Victoria’s lingering old world charm that a tourist might get while wandering the castle and its grounds is therefore contrived and nearly artificial. Craigdarroch might have been conceived as a homage to ancient British castles (p. 26), but its subsequent story is quite different. For a while, it was not much more than a white elephant that no one knew how to deal with (p. 54). It took a sustained effort by Nesbitt and others effort to enforce a view of Craigdarroch as a cultural site. In 1992 it was selected as a National Historic Site of Canada.

Does its institutional and utilitarian past make its monumental status less real? It doesn’t seem that Terry Reksten would think so. In fact, her Craigdarroch endears this aloof and fantasy-like building that still dominates the tallest hill in Victoria to the community at large. Far from being purely an ornamental reminder of a single family’s wealth, the building has a history of purpose. Reksten is not simply reminding us that the building that most symbolises the province’s romantic 19th century past isn’t all that romantic; rather, her book explores the practical exigencies behind the survival of this endearing and iconic monument. Craigdarroch is not to be celebrated simply because Robert Dunsmuir decided to show off his rise to wealth and power by building a castle, but because the city itself has claimed it as part of its larger history.

*

Matthew Vernon Downey is an honours student of History and Political Science at the University of Victoria. He currently lives in Victoria. Previously he reviewed Ken Mather’s Stagecoach North: A History of Barnard’s Express for The Ormsby Review (no. 841, June 17, 2020).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “#873 A castle for all Victorians”