#831 Don’t mention the Yukon Poet

Robert Service: The True Adventures of Yukon’s Favourite Bard

by Elle Andra-Warner

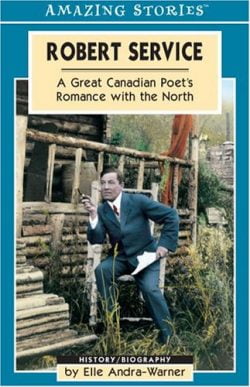

Victoria: Heritage House, 2020 (first published as Robert Service: A Great Canadian Poet’s Romance with the North, Altitude Publishing, 2004)

$9.95 / 9781772033311

Reviewed by William R. Morrison

*

As an experiment in the lasting influence of poetry in this country, I thought it would be interesting to find out how many Canadians can remember the names of one or more Canadian poets and can quote a line or two of their work. In fairness to the modern education system, which no longer emphasizes what used to be called “memory work,” the survey sample would be confined to English speakers over fifty, educated in this country. Because of the virus wreaking destruction while this review is being written, it has been possible only to ask the question at a social distance. Since it must be done orally (to prevent people googling for the answer), the sample will of necessity be small.

As an experiment in the lasting influence of poetry in this country, I thought it would be interesting to find out how many Canadians can remember the names of one or more Canadian poets and can quote a line or two of their work. In fairness to the modern education system, which no longer emphasizes what used to be called “memory work,” the survey sample would be confined to English speakers over fifty, educated in this country. Because of the virus wreaking destruction while this review is being written, it has been possible only to ask the question at a social distance. Since it must be done orally (to prevent people googling for the answer), the sample will of necessity be small.

Having said that, though, the results are interesting. Half of those questioned could not recall the name of a single poet, a dispiriting but not surprising outcome. Of the half who could, every one mentioned Robert Service, either by name, or as “that Yukon poet.” One mentioned Robert Frost, but on questioning, realized that he was thinking of Service. One knew not only his name but that of a living poet as well: Lorna Crozier, recently retired from the writing department of the University of Victoria, not far from here. None mentioned the name of a winner of the Griffin Prize, of which more later.

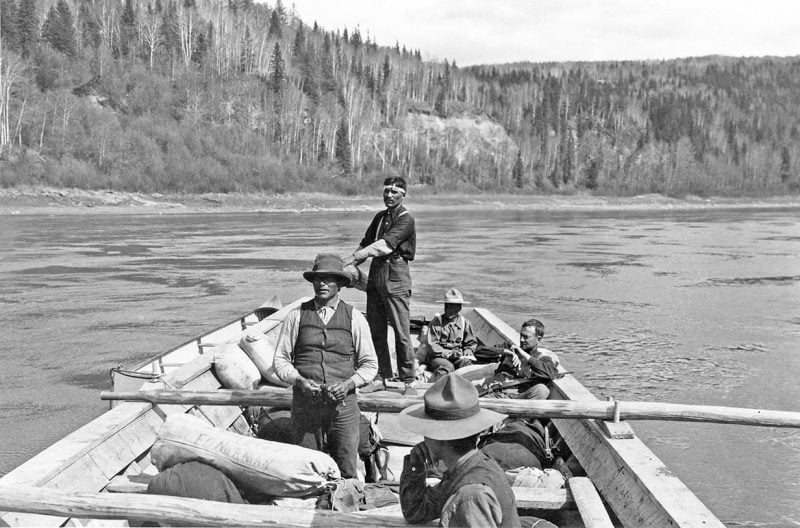

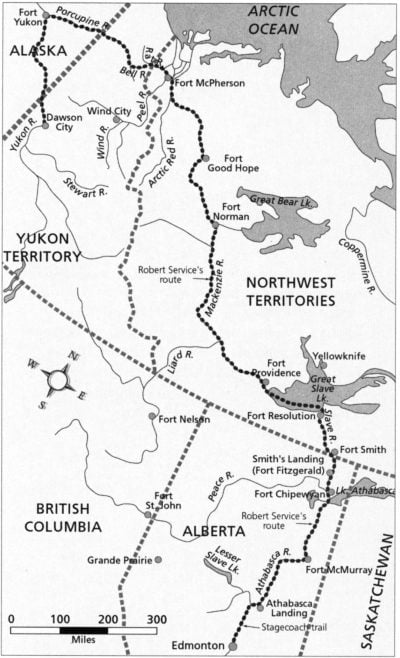

If anyone who ever wrote any kind of poetry in this country deserves a biography, it would seem to be Robert Service. Born in northern England in 1874, he led a compulsively adventurous life that took him all over the world, skirting danger almost obsessively. Elle Andra-Warner’s account of his adventures makes one realize how lucky he was to live to be eighty-four: his trip to Yukon via the Porcupine River route, taken against the advice of people who knew it far better than he did, almost ended in disaster, as did several other episodes in his life.

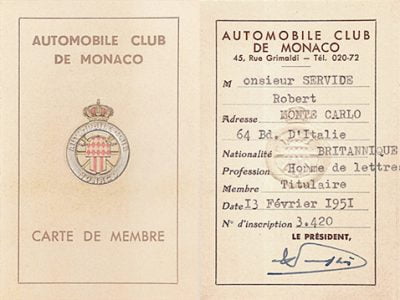

He was compulsive about writing, too. He wrote poetry constantly, and adventure books in prose, volume after volume, from his first poems as a bank clerk in Scotland in the 1880s until his last book of verse, published in 1956. Typically of his genre, it was called Rhymes for my Rags, though long before that date, his writing had made him wealthy.

Andra-Warner’s book, first published in 2004, is a straightforward though entirely pedestrian account of its subject’s life, a task probably facilitated by the fact that Service wrote two autobiographies. It’s quite short, a hundred and twenty pages of text, including a good many photographs. The title — the “True Adventures” of the man — is a bit off-putting: have we previously been misled by false adventures? Does it reveal anything about his life that any reader of his autobiographies would not already know? The answer is no. And, rather astonishingly, it quotes only a dozen lines of his poetry, none of it familiar, and none of it having much to do with the Klondike. It talks at length about the effort Service put into his poetry, but it lacks any analysis of his life’s work. Why was he “Yukon’s favourite Bard?” He was a prolific poet, amazingly so. But was he a good poet? This book does not consider this question, the answer to which depends a good deal on how you view poetry.

In his lifetime, Service was called “The Canadian Kipling” and “The Bard of the Klondike.” The first has a good ring to it, but isn’t accurate: Kipling had a serious purpose in life — to glorify the British Empire — whereas Service wrote out of inner compulsion to entertain, not preach, and mostly for money. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. When Samuel Johnson said that “no man but a blockhead ever wrote, but for money,” he spoke a truth that many authors might acknowledge. And how his books did sell. The first and most popular collection of his poems, Songs of a Sourdough, published in 1907, was the first commercially successful book of poetry ever published in Canada. By the time Service died, it had sold three million copies. That is a remarkable figure, and it wouldn’t be surprising to learn that this constitutes a number greater than the total of all other books of Canadian poetry ever published, certainly in his lifetime and probably since.

Why was it so popular? A large part of the answer is that Service was lucky and entrepreneurial enough to tap into one of the most famous and widely-followed episodes in the history of North America, and certainly that of Canada. The Klondike gold rush of 1897-99 focussed the attention of much of the world on this hitherto obscure corner of the continent, and brought tens of thousands of people to it. Coming just after one of the worst economic depressions in history, it promised riches to those who were prepared to shoulder the risk and effort of a trip to the Klondike. Even after the gold rush had faded, its legend lived on, in the writings of Jack London, a film by Charlie Chaplin, and in many other articles and stories. As late as the 1950s the Quaker Oats Company bought some land near Dawson City and launched an enormously successful advertising campaign centred on a deed to “one-square inch” of the Klondike. Twenty-one million of these deeds were given away in cereal boxes, and people still write to ask the Yukon government if they are worth anything (they aren’t). Service channelled this enormous interest and excitement in his writing. In a way, his poetry could hardly fail.

But is it good poetry? The answer to this question was supplied by Service himself, who said on many occasions that what he wrote was not poetry, but verse. The difference between the two is that poetry has a serious purpose: to enlighten, to teach, to reveal deep truths, whereas verse has one purpose only: to entertain. Canadian poets are eligible for the Griffin prize, the most generous of several poetry awards made annually in this country. The winner is awarded $65,000, and the runners-up $10,000 each. The Griffin website publishes critiques of poetry that show how much deeper the work is than simple popular verse. The commentary on a poem called Apparition of Objects notes that “Individual lines and phrases taken on their own, with no assumed relation to the lines preceding or following, are pleasurable and evocative fragments unto themselves,” and that “The poem’s brief, uncluttered lines, virtually devoid of punctuation, allows each word to seem to breathe expansively on its own.” This is poetry, nothing like what Service wrote, and to be fair to Service, he knew this, and did not claim to be a poet.

In the early twentieth century and later, verse had a much stronger hold on public taste than poetry did. Service was not the only popular versifier; many others wrote for the newspapers, of whom the most famous was probably Edgar Guest (1881-1959), of “it takes a heap o’ living to make a house a home” fame, whose work is much like that of Service, but with a more moral tone. And there is still an audience for such verse, as the popularity of “Cowboy Poetry” still shows.

As a versifier Service was a huge success, both commercially and in the long run culturally through the legacy of his work. He would never have been considered for the Griffin prize if it had existed in his lifetime, but his verse made him popular, wealthy, and famous. He wrote over a thousand poems, several novels, and published forty-five collections of verse. And his legacy has lasted.

Not surprisingly, scholars have given Service’s work short shrift. As early as 1926, Archibald MacMechan of Dalhousie University’s English Department was scathing:

The sordid, the gross, the bestial, may sometimes be redeemed by the touch of genius; but that Promethean touch is not in Mr. Service…. ‘Sourdough’ is Yukon slang for the provident old-timer…. It is a convenient term for this wilfully violent kind of verse without the power to redeem the squalid themes it treats. The Ballads of a Cheechako is a second instalment of sourdoughs, while his novel The Trail of ’98 is simply sourdough prose.[1]

Reviewing one of Service’s later books, the Canadian scholar Northrup Frye remarked in 1952 that, “There was a time, fifty years ago when Robert W. Service represented, with some accuracy, the general level of poetic experience in Canada, as far as the popular reader was concerned…. there has been a prodigious, and, I should think, a permanent, change in public taste.”[2]

Well, perhaps. But every year tourists travel to Yukon to retrace the Trail of ’98, and a surprising number of them can quote lines or even whole poems from his early work: “There are strange things done in the midnight sun by the men who moil for gold,” “A bunch of the boys were whooping it up in the Malamute Saloon.” The words just roll off the tongue, and the stories are lots of fun, some with a moral and some without. That’s what verse is supposed to do, and Service was a master of the genre. It’s too bad that Andra-Warner doesn’t quote more of them; in fact if you are looking for his poetry rather than his exploits, you won’t find it in this book. Service was no Kipling, but was indeed the Bard of the Klondike. His cabin in Dawson is still a tourist attraction, where actors dressed in period costume sing and recite his most popular verses.

In fairness, though, his legacy rests on a handful of poems out of the thousand he wrote, and the vast majority of his work is sadly dated, some of it marked by excessive cuteness and sometimes racial stereotypes that are now painful to read. An example is “The Gramaphone at Fond-du-Lac,” from Rhymes of a Rolling Stone (1912), in which a trader plays records for an audience of Indigenous people:

…Then Dogrib, an’ Slave, an’ Yellow-knife brave, an’ Cree in his dinky canoe,

Confluated near, to see an’ to hear Ed’s grammyfone make its dayboo.

…

“BAD MEDICINE!” cried Old Tom, the One-eyed,

an’ made for to jump in the lake;

But no one gave heed to his little stampede,

so he guessed he had made a mistake….

Well, though I’m not strong on the Dago in song,

that sure got me goin’ for fair.

There was Crusoe an’ Scotty, an’ Ma’am Shoeman Hank,

an’ Melber an’ Bonchy was there.

‘Twas silver an’ gold, an’ sweetness untold

to hear all them big guinneys sing;

An’ thick all around an’ inhalin’ the sound, them Indians formed in a ring…

No one today would quote such stuff — the Dago in song, big guinneys sing, the cutesy spelling of Caruso and others — and quite a lot of his verse is like this. So we should perhaps ignore this and remember The Bard of the Klondike for his famous early poems that still resonate with people who love a rollicking story told in verse.

*

William R. Morrison has taught History at Brandon University, Lakehead University, the University of Victoria, Duke University, and the University of Northern British Columbia, where he retired as Professor Emeritus of History. He is author, editor, and co-author of sixteen books on Canadian History and Universities. He lives in Ladysmith, BC.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] Archibald MacMechan, Headwaters of Canadian Literature (Toronto: New Canadian Library, 1974), pp. 219–221.

[2] Northrop Frye, Letters from Canada – 1952, The Bush Garden (Toronto, Anansi, 1971, p. 189.