#820 Calgary and the world awry

Watching a Man Break a Dog’s Back: Poems for a Dark Time

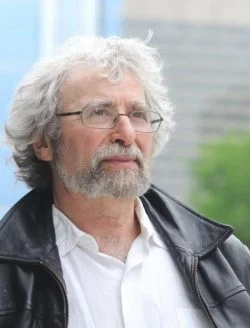

by Tom Wayman

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2020

$18.95 / 9781550179125

Reviewed by Emma Rhodes

*

Award-winning Canadian author Tom Wayman has returned with another poetry collection in Watching a Man Break a Dog’s Back: Poems for a Dark Time. His audience, he writes, is “people who couldn’t draft or read a poem/ or a book review if you paid them” (“Rant: Who I Write For,” p. 89). As a recent university graduate in English Literature and Creative Writing, I may not quite be his intended audience, but I’m delighted to share my thoughts on this impressive collection.

Award-winning Canadian author Tom Wayman has returned with another poetry collection in Watching a Man Break a Dog’s Back: Poems for a Dark Time. His audience, he writes, is “people who couldn’t draft or read a poem/ or a book review if you paid them” (“Rant: Who I Write For,” p. 89). As a recent university graduate in English Literature and Creative Writing, I may not quite be his intended audience, but I’m delighted to share my thoughts on this impressive collection.

In Watching a Man Break a Dog’s Back, Wayman tackles first the world, then individuals, and then language and writing itself. This is no small undertaking. Many writers who have attempted to tackle “the world” in their writing have come across as pretentious or insensitive. This is not so with Wayman, who avoids pretension by immersing himself in the raw material and detail of his poetic work. He does not place himself above or outside the world he exposes.

The book is broken up into three sections: “O Calgary: The World Awry;” “Jazz on a Rainy Afternoon: Elegies;” and “A Door in a Wood: Words.” In each, he narrows his scope more and more, from the systemic problems associated with industry and capitalism, to individual life and death, to the metaphysical work of writing and use of language itself.

In “O Calgary: The World Awry,” Wayman uses the City of Calgary to represent universal urban problems. I grew up not far from Calgary, and I felt excited to find my home represented here. Wayman’s image of Calgary is not the sweet, simple, naive representation of the kind we want to read when our homes are represented in literature. Yet I did not feel slighted or hurt, because Wayman holds an attachment to a truth about the constant search for profit by industry and capital — that I have witnessed in Calgary and elsewhere. Calgary serves as a microcosm for ideological and political problems present all over the world. Indeed, it represents “the world awry.” Focussing on a single city allows Wayman to engage with concepts that otherwise might have been too broad to grapple with. For Wayman, Calgary is the right size to catch, examine, and reveal to readers what is hidden beneath the facade.

A poem depicting police brutality, “Restoration of Order,” opens the book and sets the tone. The first stanza describes a police officer beating a protestor’s head with a club. Wayman draws attention to the horror — and irony — of this brutal incident:

The uniformed arm

holding the weapon

descends again: an elbow raised

to protect its body

fractures, a chip of bone from a skull

is driven into the membrane intended to protect the brain (p. 4).

What is intended to protect is broken down here on multiple levels. The officer does the breaking; the membrane breaks. Wayman draws out the scene and slows it down to examine everything that is wrong and cruel about the distressing event.

“O Calgary” employs an epigraph from the American poet Joseph Stroud (born 1943) that serves as the book’s title: “In Calgary/ I saw a man break a dog’s back.” Wayman’s poem is broken into many sections, some of which seem unbelievable, like money flooding “the banks along the Bow/ sweeping hundreds of replicas of the same ample house/ out onto wheat fields” (p. 14). These are interspersed with believable yet just-as-disturbing descriptions of people being fired and escorted out of buildings, having their living taken from them, and being told “we don’t want no trouble,” along with horses broken and finished in wagon races and angry feet in cowboy boots kicking the vulnerable.

Ending this section, the poems “Advisors” and “How I Achieved Tenure,” address how dialogue inhibits people from attempting to change this fractured world, but Wayman places himself as drowning in this very system. He recognizes that he and his readers are immersed in the very system he writes of. He does not excuse himself from the world he reveals to us.

In the second section of the book, “Jazz on a Rainy Afternoon: Elegies,” Wayman focusses on individuals. “Wind Elegy” (p. 60) and “Not the Wind” (p. 75) both describe the effect of someone’s passing on their community. “Wind Elegy” describes how everything is interrelated, inadvertently affecting one another; wind affects waves even if its purpose is simply to blow, and a village affects lives even if its purpose is only to create space for us to inhabit. A village is also a “father,// stepson, brother, husband,/ assessor of dietary trends” (p.61). Once a life in the village dies, though, the village remains “occupied by its Saturday’s// activities, its Wednesday’s” (p.62), and the wind too continues filling its roles whether or not the waves move.

Using wind in a different way, “Not the Wind” describes the debilitating result of a loved one’s death even while the village moves forward. In “Wind Elegy,” life and its natural forces continue; while in “Not the Wind,” they can freeze, and the wind has nothing to do with it. Grief holds this power:

It’s not the wind

pouring off the lake from the north

that hurries me forward

faster than I thought possible

[. . .]

Yet this driving power can also stall

abruptly — as inexplicable as any action it manifests —

so that I falter, trip

at the sudden lack of motion.

[. . .] My days flap useless as a sail

when the breeze stills

or shifts (p. 75).

Reducing his scale even smaller, in the third section (“A Door in a Wood: Words”), Wayman narrows in on language and writing itself, and he gets metaphysical and playful. He examines why he writes and who he writes for. He examines words: their power, purpose, function, why they can be frightening or amusing, and more, but he does not take himself so seriously that he becomes alien to readers. The last poem of the second section, and a sort of introduction to the third, “Last Testament” opens with:

Before I was born

I had nothing to say. I wasn’t asked

a single question

and was completely silent.

No wonder I talk so much

now that I can.

Centuries without the benefit

of my presence

have to be made up for

by my words (p. 80).

Watching a Man Break a Dog’s Back: Poems for a Dark Time offers so much more to be unpacked. I am impressed by how much is contained within its 115 pages, and how masterfully Wayman tackles so many, and such drastically different, subjects while remaining sympathetic, cohesive, and often playful.

*

Emma Rhodes is a recent graduate from St. Thomas University in Fredericton, New Brunswick, with honours in English Literature, major in Comparative Literature, and a concentration in Creative Writing. In 2019-20 she worked as an intern at Goose Lane Editions in Fredericton. Her creative work has been published in the Temz Review, MELTDOWN, elm+ampersand podcast, and Sonder Midwest magazine. Other work has been published in Plenitude Magazine, The Puritan, and The Miramichi Reader. She plans to pursue graduate studies at Queen’s University in the fall.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster