#804 Gibson’s poetic pyrotechnics

How She Read

by Chantal Gibson

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2019

$20.00 / 9781987915969

Reviewed by Renée Sarojini Saklikar

*

On March 12, 2020, Chantal Gibson’s How She Read was shortlisted for both the 2020 Dorothy Livesay and Jim Deva prizes of the BC and Yukon Book Prizes. Winners will be announced on September 19th.

As well, How She Read has been shortlisted for the Griffin Poetry Prize and longlisted for three awards offered by the League of Canadian Poets: the Gerald Lampert Memorial Award, the Pat Lowther Memorial Award, and the Raymond Souster Award. — Ed.

*

As is often the case, this year’s BC Book Prize finalists are worthy of time and attention, which is a credit to our independent literary presses and the BC Book Prize judges, not to mention the poets.

As is often the case, this year’s BC Book Prize finalists are worthy of time and attention, which is a credit to our independent literary presses and the BC Book Prize judges, not to mention the poets.

What a gift it is: to sit with a book of well-made poetry, perhaps never more so than in the precarious moments of a global pandemic.

Chantal Gibson’s How She Read fuses literary, poetic, and visual arts in a tour de force that showcases the talents of Caitlin Press and Gibson’s own visual and writing practice. Her work reminds me of a book blurb I once read to Ondaatje’s The Collected Works of Billy the Kid: “one of those rare books that knows where it’s going and goes there” (Saturday Night magazine, 1970).

Gibson teaches at the School of Interactive Arts & Technology at Simon Fraser University and self-describes as an artist-educator. Everything about her book points to time well spent in both a writing lab and an artist’s studio.

As well, How She Read bears evidence of a fruitful collaboration between author and publisher: this book is a pleasure to hold: from the haunting cover, with its image of Gibson’s school-aged mother; to the beautiful colour and black & white paintings and photographs that populate its pages; to the variety of poetic forms that bridge from the traditional (sonnets) to concrete poetry (the visual use of lines, space, and deconstructed language).

And then, to top all that off, the book operates as a treatise examining race, class, and gender.

Recently, at a poetry reading, Gibson spoke about the title, and explained how the “mis/grammar” of the title, “How She Read” versus “How She Reads,” is part of her deliberate exploration of the way language “quietly embeds” imperialist notions in everyday things. In this, her work is reminiscent of Toronto poet M. NourbeSe Philip’s seminal Zong! (2008).

Conceptually, Gibson organizes her book into three sections, plus a Foreword and an Afterword that operate as mini-chapbooks, cleverly constructed to both prepare us for what will greet us on “the journey of the book,” and then, at the close, by using both visual art and poetics, invite us to see the entire work as a sum greater than the parts of the whole.

“Foreword: How to Use Your Book. Lesson 1 from The Coloured Girl’s Writing Handbook,” is perhaps also a signal to the reader on how to read How She Read (!). It is followed by an epigraph from a 1948 Macmillan Grade 4 school text, The Canadian Pupil’s Own Vocabulary, which is itself heavily redacted by blackout boxes superimposed onto the words.

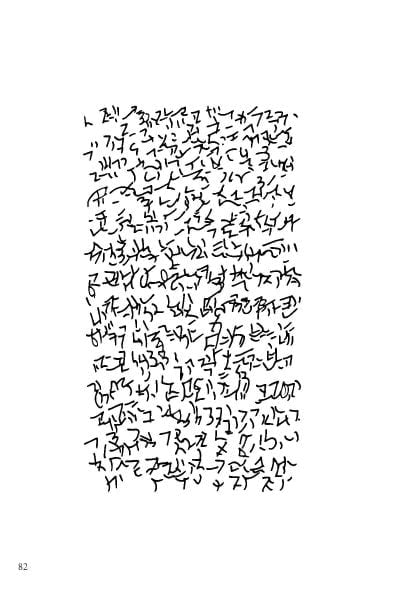

And this is just the beginning. This same poem contains a series of replicated pen marks. “This shorthand,” Gibson explains in her Notes section, “is derived from the process of deconstructing my own cursive handwriting. If you can’t read it, you’re not meant to.”

Wow. That’s bold! We, the readers, are left with a choice in the face of this authorial declaration. Shall we continue with the book? I hope all readers will make that choice, for Gibson rewards with a cornucopia of visual and written bravado.

The provision of short explanatory footnotes for some of the poems serves to deepen our appreciation for the “backstory” process involved in “why this poem,” and they serve as way-finders, allowing the reader to go back and think about the way poems are presented on the page.

The eponymous opening poem contains a line depicting the author’s cursive handwriting, embedded into the lines of the poem to create the effect of a prologue:

Oh, how she read this. Girl

beloved daughter of daughters

blood, kin, and kind

sagacious grammarian

post-fly phoneticist

every syllable she say be sapphires

…

and the final three lines, a kind of fiery anthem,

every word she speak be a teeth-sucking act of resistance

every word she write be a battle cry

every tap of her pen be the beat of an ancestor’s drum.

Already such riches: structural forms, the introduction of visual images, word-play, the layering into these linguistic devices, and a contemplation of both self and societal forces including the class and race underpinnings of things we might take for granted, such as grammar.

As we go deeper into How She read we might choose to use the Foreword as a guide to explore Gibson’s opening 16 poems. Her Grammar of Loss poems function as memoir and begin the book’s investigation into the author’s life and the lives of her mother and other women of colour.

“I’ve come for your demons” is the opener: a kind of Bad Girrl Ballad play on what “They” teach us in school, with the epigraph, “the following list contains words commonly known as spelling demons” from a 1947 Canadian Edition of The Pupil’s Own Vocabulary Speller (p. 12). To that epigraph, the poet responds with this rebuttal:

I’ve come for your demons

to trouble the lessons

to enough the letters

to birthday the disappeared.

This poem is followed by a series of visual poems that immediately signal to us that we had better pay attention: something subversive is happening here.

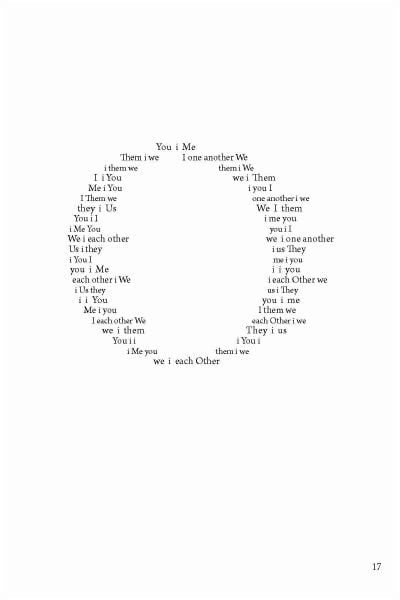

For example, the concrete poem “reciprocal pronouns” is constructed in three parts with pronouns, such as “You i Me/we i Them/” and so on, arranged to form the shape of an O, with the first part (p. 15), being less populated with pronouns, and then progressively becoming more dense with many arranged patterns of these words, so that by p. 17, “I each Other we” populate in a well-defined O shaped cluster.

As readers, we are invited here to think not only about grammar and the theory of syntax — about what are pronouns and their antecedents, after all — but so much more: about space, about lines, about language, about ways of seeing.

As another example of Gibson’s multi-layering technique, the poem run-on is a collection of long run-on “sentences” that tell the story of a family, “all inside watching Roots it’s January 20,” that upends the notion of that high school bromide, both necessary and pedantic, “Don’t use run-on sentences!

What appeals most about this poem is the way the run-on lines are used to create the visual effect of a block of blank verse, that is/ is not blank verse but “just looks like it, sort of.”

Here, such dicta are played with, showing how narrative is at once a fluid negotiation between “the rules of writing,” if the story is exclusively a transaction between reader and author; but also, so much more, particularly, if the author wishes the work to be not just alive on the page as text, but also evoke an aural/oral story-telling experience.

Each poem in the Grammar of Loss takes its title from a grammatical construction, such as the poem synonyms & antonyms, which is a complex examination of how women of colour portray each other: “You I her the East Indian/woman/a black braid twisted,” and further into the poem, the irregular lines drift and collapse across the page, opening up possibilities of meaning:

You I them her children brown

eyes dark n watery immigrant brown shit

brown newcomer brown black hair knotted tight atop

their tiny heads empty spaces broken milk teeth curried laughter

This stark recitation of racist cruelty is perhaps meant to unsettle and illustrate the kind of “word profiling” in narrative description, which can become, when un/examined, common place in everyday language.

Perhaps the phrases uttered here are words the speaker has heard others say: “You I Me/gap-toothed smiling already-knowing flinching /was possible,” (p. 28). I find it brave and risky to “go there.” I’m not sure how successful the lack of narrative context is here: where is this happening, why is it happening, what is “triggering” the outpouring of words: perhaps it’s an exchange or an offering of a food gift, from one woman to another?

But if one pauses and then flips back to that Foreword, and then again to those concrete pronoun-poems, perhaps the poem establishes itself better:

you I Her Nana

beige cardigan smile heirloom recipe box coffee-

stained clippings…

….

large bowl of skinned tomatoes her un-

flinching hand the moment

it touches yours

What I value about this “problem poem” is the way it dares to utter how race “colours” our perception, no matter what our identity. We can’t escape ourselves, as Gibson suggests, with her use of pronoun triplets.

The speaker of the poem is rendered in multi-voice without formal punctuation marks such as the comma to separate “You I Her,” which has the effect of destabilizing our sense of “who is speaking to whom,” and so both reader and the speaker in the poem are implicated in a nuanced relationship.

Many of the other poems in How She Read are precise, formalist constructions with embedded wordplay, such as homonyms:

You said, Hand me that knife, girl, handle first.

I whispered into my sorry-looking finger-

nails, prayed you could make Nana’s pastry from

scratch, keep that shiny blade away from your skin,

and stop the chemo sakes enough to cut 1 finger

In this poem, in the second line after the word, “whispered,” a series of four pen-like graphic inscriptions floats into the line, the author/speaker’s notes from a diary or journal, fragmentized, replicated, and inserted into a poem dense with tragedy (her Nana’s illness), “til your backhand reminds me I am your stuff.”

Throughout the seven stanzas of five lines apiece, these “pen mark fragments” appear twice and act as a kind of redacted leitmotif.

The whole construction of the poem is a kind of sestina with the “Hand me that knife girl, handle first” line repeated in different ways, for example, “Don’t ever let a man lay a hand on you, girl,” with each stanza moving us from a younger speaker’s voice to her older self through the course of the poem.

The next section of the book, Icons, consisting of eight intricately-composed, multi-genre poems that put the historical context around the personal with narrative lines that perform as the beating pulse of muscle: there’s an edge here amid the play with words and meaning.

In Don’t Call Me Minty: A Revisionist Heritage Minute, we see and read a fierce reimagining of the Harriet Tubman story where the narrative prose of a persona-poem imagines Harriet taking down and talking back to those “comfy” Heritage Minute mini-films that many of us might have encountered on TV or in the endless time before a cineplex movie actually begins.

Gibson, again, as she does consistently through out the book, makes use of epigraphs, in this case from Historica Canada: “She did follow someone who was making his way to freedom, only to suffer a serious head injury,” and then juxtaposes that version of the historical Harriet Tubman with her own, in the voice of Harriet herself, in a series of little “historica” boxes of text, with the first line “I did not follow” undermining the received wisdom of the epigraph:

I did not follow someone

I was in a dry good store with a plantation cook

buying items for the house

I did not follow Barrett’s slave,

the someone in the store who left his plantation work….

The importance of this poetic work can’t be overstated.

Too often, the history of women of colour, if not entirely redacted from “the books,” is instead mis-characterized and even bowdlerized to create a weakened image instead of presenting more complex characters who somehow, against many odds, managed to do incredible things. The poems in Gibson’s book contribute to a redressing of that imbalance.

In the third section of the book, Crossing the Punctum — the phrase, I gather, a reference to Roland Barthes seminal book, Camera Lucida [1980]) — Gibson elaborates and builds on the merging of the personal with the historical.

She continues her use of a variety of traditional forms, for example the letter as a poem in blocked out prose poem texts (the “Viola Desmond” poem, p. 77), but upended and subverted to illustrate and challenge comfortable notions.

This approach finds trenchant voice in “Cease n Desist: From the Desk of Viola Desmond,” which begins, “Dear Government of Canada,” Feb. 4 2012.” In four stanzas, this poem eviscerates the kindly notion that our recent Canadian ten dollar bill, with its stunning reproduction of Viola Desmond’s face, is “a nice gesture:” “…While I recognize the/ concentrated effort to make right the past and restore/ my good name/ I question the methods you’ve employed/ to place me in this position of high regard. Please stop….”

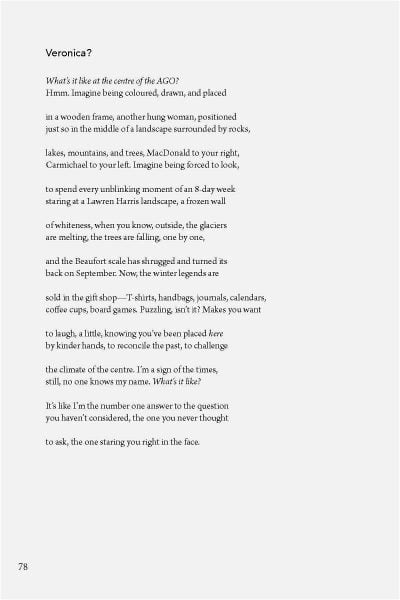

And then there’s the use of couplets in “Veronica?”, a poetic monologue in the tradition of Robert Browning (My Last Duchess), both describing and interrogating the subject of a painting by Canadian artist Yvonne McKague Housser (fully reproduced here in glorious colour) that hangs in the Art Gallery of Ontario, “Untitled, c.1933,” depicting a brown-black young woman:

What’s it like at the centre of the AGO?

Hmmm. Imagine being coloured, drawn, and placed

in a wooden frame, another hung woman, positioned

just so in the middle of a landscape surrounded by rocks,

….

… Makes you want

to laugh, a little, knowing you’ve been placed here

by kinder hands, to reconcile the past, to challenge

the climate of the centre. I’m a sign of the times,

still, no one knows my name. What’s it like?

It’s like I’m the number one answer to the question

you haven’t considered, the one you never thought

to ask, the one staring you right in the face.

Gibson’s poetic skill is on full display here, rendering naturalistic language with ease within the shape of couplets, both poignant and outraged.

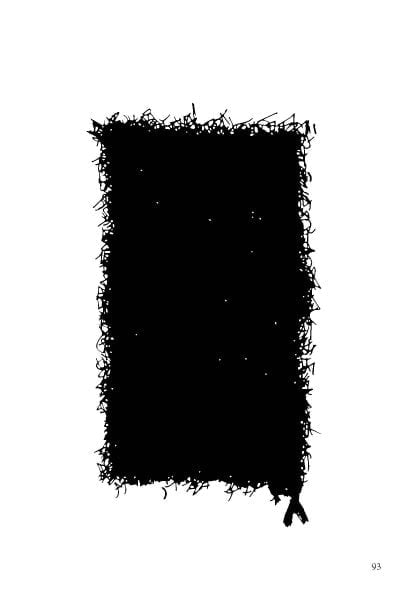

One might argue, though, that it is the Afterword of this book that entrances, as if all the pyrotechnics of Gibson’s poetics were not enough. Here we have the invention of a new way of communicating poetry. Take a look at the poem at right:

We see here the building of those first cursive lines that greeted us in the Foreword, now arranged in fourteen lines, and then morphing from that, into dense blocks of black on white colour. Thrilling.

Gibson’s How She Read begins with the English of Canadian grammar books circa the late 1940s before subverting the syntax of those rules with her memoir patois and cursive replications, and then closes with that most English and ancient of constructions, the sonnet, revamped and in your face. Take that!

Gibson is a kind of Mercutio, her dazzling skill making any reader, by the end of this remarkable book, a bit grave and peppered.

Read this book and be rewarded by anyone’s reasonable question: what is a poem? Well, by gum, it’s what you make it, Gibson seems to be saying: it’s how much you read, how much you practice form poetry and then build on that practice, how much you take the time to learn “the rules” and then, with boldness, break those rules to see “how you read.”

*

Renée Sarojini Saklikar recently completed her term as Poet Laureate for the City of Surrey. Her first book, children of air india, (Nightwood, 2013) won the 2014 Canadian Authors Association Award for poetry, and Listening to the Bees (Nightwood, 2018) was a BC bestseller. She co-edited The Revolving City: 51 Poems and the Stories Behind Them (Anvil Press/SFU Public Square, 2015,) a City of Vancouver book award finalist. Her chapbook, After the Battle of Kingsway, the bees, (above/ground press, 2016), was a finalist for the bpNichol award. Her poetry has been made into musical and visual installations, including an opera, air india [redacted]. Renée was called to the BC Bar as a Barrister and Solicitor, served as a director for youth employment programs in the BC public service, and now teaches law and ethics for Simon Fraser University and creative writing at SFU and Vancouver Community College. She curates the popular poetry reading series Lunch Poems at SFU and serves on the boards of Event magazine, The Capilano Review, and the Surrey International Writers Conference. She belongs to the League of Canadian Poets and The Writer’s Union of Canada (TWUC), is active on the TWUC Equity Committee, and was Guest Poet for Art Song Lab 2019. She is working on two projects: an epic-length sci-fi poem, THOT-J-BAP, that appears in journals, anthologies, and chapbooks, and a series about self-help and fashion.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster