#796 John McLoughlin of Rainy Lake

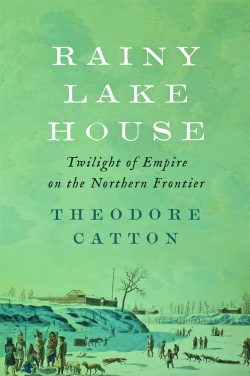

Rainy Lake House: Twilight of Empire on the Northern Frontier

by Theodore Catton

Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017

$32.95 (U.S.) / 9781421422923

Reviewed by Sarah Carter

*

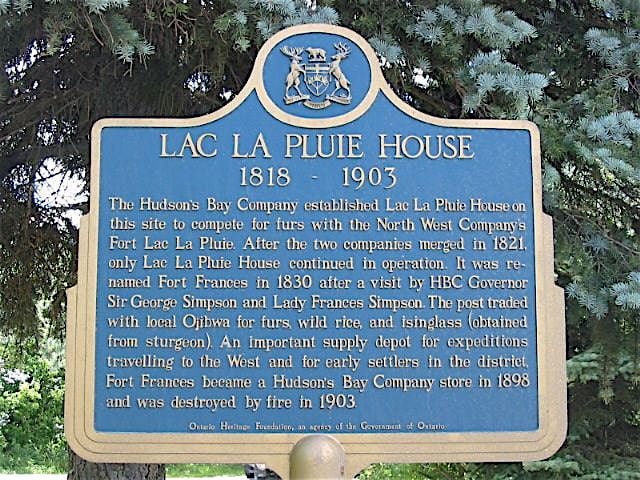

The pandemic crisis descends as I write this review and my first thought is that this book will be a welcome diversion from the anxieties and upheavals we all face. This absorbing, creative study takes us deeply and thickly into the world of the early nineteenth century on this continent with a focus on Rainy Lake (Lac La Pluie), located on what is now the border between Minnesota and Ontario. There were several trading posts here including the Hudson’s Bay Company’s (HBC) Rainy Lake House (later Fort Frances). While this location may seem remote even today, it was in fact an important hub on the highway of the fur trade, as it was directly on the line of communication from Grand Portage (Fort William) to Red River and Lake Winnipeg, at a time when people frequently crisscrossed the continent by canoe.

The pandemic crisis descends as I write this review and my first thought is that this book will be a welcome diversion from the anxieties and upheavals we all face. This absorbing, creative study takes us deeply and thickly into the world of the early nineteenth century on this continent with a focus on Rainy Lake (Lac La Pluie), located on what is now the border between Minnesota and Ontario. There were several trading posts here including the Hudson’s Bay Company’s (HBC) Rainy Lake House (later Fort Frances). While this location may seem remote even today, it was in fact an important hub on the highway of the fur trade, as it was directly on the line of communication from Grand Portage (Fort William) to Red River and Lake Winnipeg, at a time when people frequently crisscrossed the continent by canoe.

In September 1823, three men met by chance at Rainy Lake: Major Stephen H. Long (1784-1864), of the U.S. Army Topographical Engineers, who was returning from an exploring expedition west and north of Lake Superior; Dr. John McLoughlin (1784-1857), in charge of the HBC post; and John Tanner (1780-c. 1847), the “white captive” born in Kentucky, who had lived for three decades with the Plains Anishinaabe, mainly in the Red River country of present-day Manitoba.

Theodore Catton, research professor of history at the University of Montana, intertwines the stories of these three very different men. We learn about their backgrounds, their distinct points of view on issues of race and Indigenous people, some of the shifting dynamics of the fur trade, and the history of North America. The three were witnesses to, and participants in, many of the momentous events that altered and shaped imperial and local power structures, but they provide different perspectives. On a more analytical level, Rainy Lake House is about “the subjectivity of perception and the challenge of constructing truth from multiple points of view” (p. 5).

Major Long, from New Hampshire and educated at Dartmouth College, undertook four other major expeditions west, exploring land and resources and recommending the location of military outposts and railways for American authorities. At Rainy Lake in 1823 for two days on his return east from his fifth and last expedition, Long met Tanner, who was recuperating from a serious wound inflicted by a would-be murderer who was likely hired by his Indigenous wife. Tanner was leaving his life with the Plains Anishinaabe behind, seeking his American family, and trying to find his two missing daughters who had run away from the post and who, he feared, would be raped by HBC men. Abducted as a boy of nine in 1789, Tanner was eventually adopted by an Ottawa/ Anishinaabe woman, Netnokwa, and he became thoroughly assimilated into his new family’s culture, living as a hunter and trapper, marrying twice, and having many children.

McLoughlin, born in Quebec, first worked as a physician with the North West Company (NWC) and rose in the ranks, helping to negotiate the merger of the NWC and HBC in 1821. He was then appointed Chief Factor at Rainy Lake House and placed in charge of a huge territory. He had just returned from a ten-week trip to Hudson Bay on the night of Long’s arrival, anxious to reunite with his wife and children, all part Indigenous, who lived with him at Rainy Lake.

Catton approaches the challenge of collective biography through 45 short chapters divided into eight parts that deal in turn with phases in the lives of the Explorer (Long), the Hunter (Tanner) and the Trader (McLoughlin). Of the three, Catton is most sympathetic to McLoughlin, a doctor and humanitarian, who was concerned about the welfare of all people, and who worked (unsuccessfully) toward an inclusive society that encompassed both settler and Indigenous people. Assigned in 1824 to the HBC’s Columbia district, Chief Factor John McLoughlin would soon play a major role in the history of the Columbia Department, a vast administrative region west of the Rocky Mountains that now includes British Columbia and the American Pacific Northwest.

Long is the least likeable, in his attitudes toward Indigenous people, his smug superiority, and total devotion to the interests of settler society. Catton argues that Long’s description of the Great Plains as a desert helped prepare the ground for the “Indian removal” policy. Married to a settler woman from a prosperous Philadelphia family, Long abhorred “cultural mixing” and saw Tanner as personifying depravity and degeneracy. Tanner is a tragic figure, at home in neither the Indigenous or settler worlds. He “lost his Indianness as well as his whiteness. Attempting to straddle two cultures, he found himself rejected by both” (p. 291). Violence and conflict characterized Tanner’s life. He ended his days in poverty on the outskirts of Sault Ste. Marie, disappearing in 1847.

While all three men left a documentary trail, it is Tanner’s “as-told-to” autobiography that is the most remarkable and detailed, constituting the heart of the book. He was illiterate, and he worked with scientist and surgeon Edwin James to produce A Narrative of the Captivity and Adventures of John Tanner, first published in 1830. (James had coincidently participated in one of Long’s expeditions and had collaborated with the Major on his 1823 Account of an Expedition from Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains.) In a Postscript on “John Tanner as a Source,” Catton draws on a number of authorities who agree that Tanner’s is a rare, firsthand, and authentic “Indian voice.” I assigned excerpts from Tanner years ago when I taught at the University of Winnipeg, and my Anishinaabe students were amazed at his knowledge of their beliefs and stories connected to the cherished heritage sites that he described. Catton does, however, consider the role of James in helping to shape and craft the narrative. James believed in the need to preserve and protect the landscapes and Indigenous people of North America and his views make their way into Tanner’s narrative.

The incredibly complex and diverse history of the Indigenous people of the fur trade regions and their relations with Europeans and other First Nations and their perspectives could be dealt with in Rainy Lake House in greater depth. We do learn a little about the Indigenous wives and children of Tanner and McLoughlin, but just intriguing glimpses. Sources, of course, are an issue in developing this theme. But we do learn about Marguerite Wadin McKay, abandoned by her first fur trader husband after ten years of marriage and four children. She then married John McLoughlin who became father to her children, and together they had four more children. The couple were very devoted, and she was with him at his death. One of the most important and interesting characters in Tanner’s life is his adopted mother Netnokwa, an accomplished and respected leader, hunter, and trader, but we only get a few brief glances. Tanner’s wives remain shadowy figures, and the topic of Tanner’s children might have been developed further. Some became prominent Indigenous leaders in 19th century Manitoba and beyond; one son was a Presbyterian missionary and another a leader of a Saulteaux (Plains Anishinaabe) band.

This book challenges the common misconception that Canadian history is boring. It also demonstrates that our history needs to be told outside the confines of the nation, and Rainy Lake House: Twilight of Empire on the Northern Frontier triples as a Canadian, American, and British imperial story.

*

Sarah Carter is professor of history at the University of Alberta in the faculties of Arts and Native Studies. She specializes in the history of Western Canada. Her most recent monograph is Ours By Every Law of Right and Justice: Women and the Vote in the Prairie Provinces (UBC Press, 2020 forthcoming). A collection of essays, co-edited with Nanci Langford, Compelled to Act: Histories of Women’s Activism in Western Canada, will be published in 2020 with the University of Manitoba Press.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster