#795 Choosing a seat on a plane

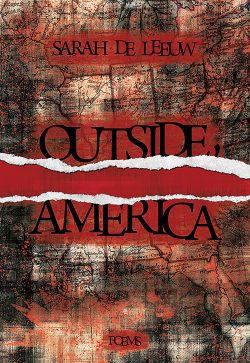

Outside, America

by Sarah de Leeuw

Gibsons: Nightwood Editions, 2019

$18.95 / 9780889713543

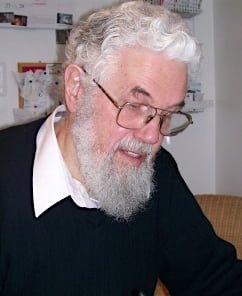

Reviewed by Christopher Levenson

*

Good poetry derives from the confluence of at least two abilities: a mastery of the full resources of the medium, language, and an unusual angle or perspective on the poem’s subject matter. All good poets achieve their own specific balance between the two. Thus, while we would probably not read Gerard Manley Hopkins for the originality of his insights but rather for the overwhelming emotive power of his language and his control over cadence, so too we read Emily Dickinson less for the originality of her stanza forms or vocabulary than for the unusual camera angles of her view of the self’s relation to the wider world.

Good poetry derives from the confluence of at least two abilities: a mastery of the full resources of the medium, language, and an unusual angle or perspective on the poem’s subject matter. All good poets achieve their own specific balance between the two. Thus, while we would probably not read Gerard Manley Hopkins for the originality of his insights but rather for the overwhelming emotive power of his language and his control over cadence, so too we read Emily Dickinson less for the originality of her stanza forms or vocabulary than for the unusual camera angles of her view of the self’s relation to the wider world.

It is all artists’ gift and privilege to imagine what they cannot see and to present their imaginings in the context of the real, everyday world by making connections that as readers we had not foreseen. This is what Sarah de Leeuw achieves in Outside, America.

At first reading many of her poems might appear casual, as if they had almost assembled themselves. Thus in “Oklahoma II,” one of several poems seen from above, from a drone or an aeroplane, she evokes the random violence of a recent tornado in a series of supposedly discrete images of “Ordinary events.”

A dog trailing her leash, barking

outside a door frame without a house.

Cicadas settled on the smooth,

sunwarmed, uncracked windshield

of a Toyota Landcruiser

Dropped into a third floor pediatrics ward.

Catfish flopping against lampposts

The same sense of surprise is evoked in “Flying north, clear cuts below,” which interprets the denuded landscape in terms of lung x-rays and of whales.

Likewise, in “J-16, 8501,” she links her dead father’s remembered conversation about discovering a baby female orca from an endangered pod to the crash that same day of Air Asia flight 8501, whose “cylindrical fuselage, scarred,/ chewed but full of the dead / seatbelts buckled and black / box pinging like an orphaned / orca, the sea bottom a telegraph / line of currents, ever quieting/ what sings and swims…”

Despite the bracing alertness of her poetry, the landscapes and seascapes she evokes with an almost scientific detachment, are not ends in themselves, but serve to establish connections. Suffused though it is with a kind of introspective intelligence, we can rarely guess at the start how it might end and suspect that the poet herself does not know, so that for both reader and writer the destination comes as a surprise and an illumination. In “October Chanterelling,” for instance, all one long sentence, the poem starts with father and daughter on a hiking trail looking for mushrooms but soon becomes much more as her father draws the poet’s attention to the fragile interconnectedness and interdependence of the plant world and our own:

how no matter how long and strong

the lichen looks, it remains fragile,

how one should not rip out other

species in the hunt for chanterelles

and the long-gilled stems of edibles

should be cut, orangey-gold stubs

left in the ground for next year because

everything that grows on earth is left

by something else, even daughters

who will leave and cross oceans or those

two red cedars, twins attached

at ankle and neck, when one falls the other

will crumble; so my father is also saying

listen, I will die one day too: look.

The locales and situations of her poems are very much those of the high tech contemporary world but their findings could rarely have been foreseen at the outset. “Seven F,” for example, starts from the most banal practical consideration, choosing a seat in a plane, but ends as a celebration of life in opposition to the German Wings flight whose pilot deliberately crashed his plane:

because there is nothing

more profound and beautiful than simply

being alive, not being killed on impact

with the Alps, breath stripped away,

oxygen masks dispensed, snow

the unstoppable descent of a man

terrified about losing his sight.

If some of de Leeuw’s poems that consist simply of lists do not for me embody the same tensions that animate her best work, and if there were a few others whose trajectories I could not follow, nevertheless the vast majority of these poems will make readers take a second look and contemplate more critically what they had seen only in passing and taken for granted. Above all, it will make them more aware of the precarious underlying unities within our endangered world.

*

Born London, England, in 1934, Christopher Levenson came to Canada 1968 and taught English, Creative Writing, and Comparative Literature at Carleton University from 1968 to 1999. He has also lived and worked in the Netherlands, Germany, Russia, and India. He has written twelve books of poetry, the most recent of which is A Tattered Coat Upon a Stick (Quattro Books, 2017). He co-founded Arc magazine in 1978, was its editor for the first ten years, and was for five years Series Editor of the Harbinger imprint of Carleton University Press, which published exclusively first books of poetry. He has reviewed widely, mostly poetry and South Asian literature in English, in the UK and Canada. With his wife, Oonagh Berry, Christopher moved to Vancouver in 2007 where he helped re-start and run the Dead Poets Reading Series.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster