#763 Beach glass on a bed of seaweed

On the Arts

by Naomi Beth Wakan

Brunswick, Maine: Shanti Arts Publishing, 2020

$17.95 (U.S.) / 9781951651091

Reviewed by Phyllis Reeve

*

Every man is at liberty to understand nothing about anything. So said Montaigne. Or at least Naomi Wakan says that he said it, and I am not going to contradict her. He certainly said something very like it. Armed with this ringing slogan, she rationalises the authority which permits her to write so ambitiously On the Arts: “If having twice been married to artists qualifies me for anything besides cleaning studios and helping with promotion, it qualifies me to have a keen eye for art.”

Every man is at liberty to understand nothing about anything. So said Montaigne. Or at least Naomi Wakan says that he said it, and I am not going to contradict her. He certainly said something very like it. Armed with this ringing slogan, she rationalises the authority which permits her to write so ambitiously On the Arts: “If having twice been married to artists qualifies me for anything besides cleaning studios and helping with promotion, it qualifies me to have a keen eye for art.”

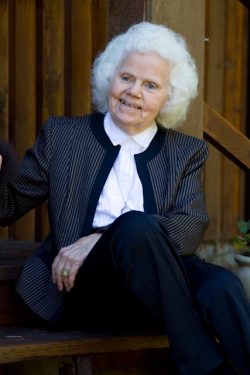

I can match that. As reviewer I can base my qualifications on a half-century parenting two art-history majors, three years volunteering at Vancouver Art Gallery, and two decades of friendship with Naomi Beth Wakan. The last disclosure should disqualify me, but it doesn’t because Naomi cheerfully takes care of the major caveats I might have provided. She admits:

Lack of knowledge has never inhibited my essay writing. Writing is always a learning process for me.

I have dilettanted through many of the arts in my lifetime and in this book.

I am not an academic who researches a subject deeply, but a skimmer who scoops up the odd angle that attracts me, such as the glint of a piece of beach glass on a bed of seaweed. Sometimes, as I am an amateur in most arts, these cullings cast a strange light on accepted concepts — the naive telling of the Emperor’s new clothes, as it were.

The reviewer is disarmed, as is the reader, and we happily tag along with Naomi as she discovers, reflects, and fits everything into a lifetime’s patterns. She has fashioned her own art — poetry, snippets of creative non-fiction and autobiography, fabric art, and embroidered shopping bags — from the stuff of everyday. As the inaugural poet laureate for the City of Nanaimo, she brought grace and initiative to her role, making what could have been a vanity position into a vehicle for joyous community education, taking poetry into buses, onto sidewalks, and within the solemn chambers of city council.

On the Arts first appeared in 2016 from Wakan’s own Pacific Rim Publishers. This svelte new edition from Shanti Arts Publishing has been re-edited, redesigned, and rearranged. The slimness of the volume owes more to change of typeface and spacing than to shedding of content, for while some content has been removed, other has been added. Illustrations have become uniformly black and white. The cover, now elegant in maroon, has eliminated the former enigmatic image by the author’s sculptor husband Eli Wakan, and replaced it with an even more enigmatic photograph of a freshly sharpened pencil. Possibly the pencil refers to the new subtitle Essays.

Could it be that the author/ publisher of the first edition was not entirely convinced that these pieces are in fact “essays”? Many are at least in part “How-to” recipes: how to see, how to make, how to read, how to arrange Ikebana — but also “how to enjoy,” plus a liberal dose of memoir.

Naomi’s curiosity is insatiable and compulsive: she finds out about something, studies it, recreates it, and shares it. These twenty-three pieces, plus introduction and afterword, range from an irreverent examination of the nature of contemporary art, explorations of food-writing and haiga (“a composite form of art, consisting of haiku, calligraphy, and a brush painting”) to recycling and film noir. She touches on art forgers, bel canto singers, and flamenco dancers. The chapter on Ekphrasis, which she explains is not “just a description; it’s a relationship,” gives us Ruskin’s verbal evocation of Turner’s painting “Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying,” Michael Dylan Welch’s meditation on Van Gogh’s “Bedroom in Arles,” and her own insight into Alice Rich’s “Dissolve.”

In her sharing, she may come across as both open and opinionated. Her statements are often firmly prescriptive. But that is okay, because, as she admits “the only art form I have come anywhere near perfecting is the art of helping others unblock.” Fortunately she is a good teacher. Her workshops and lectures have earned the gratitude and acclaim of her students, and much of her technique dominates On the Arts.

Nor is she done learning. She wonders whether, having spent years with poetry and non-fiction, she might turn her attention to the writing of short stories. Somewhat surprisingly, her model is W. Somerset Maugham (with Guy de Maupassant a close second): “Yes, I know his stories are dated but then, so am I. ”

As her eighty-eight years threaten to restrict her movements, she decides to turn that restraint to her advantage in the service of a new art form: “So my next focus will be on the domestic front rather than the world stage, and my late-life career will be to practice the art of domesticity,” an art which “might well be described as a long-term happening, a multi-room installation.”

Naomi’s investigation of the vexed question “What is Art?” begins early in the book. The nearest she gets to an answer is “Art is life lived awarely” (her italics). She continues:

Art is asking that you become more aware in the everyday — aware of how you take out the garbage and how you wash the tines of a fork. Yes, as far as what art is, I do think I have something here, don’t you?

And since I am ending with the beginning, this poem, “The Start of Modern Art,” which sums up the book, is placed before the Table of Contents or Introduction. It is accompanied on the opposite page by a black & white reproduction of Kandinsky’s “Free Curve to the Point — Accompanying Sound of Geometric Curves” (1925):

The start of modern art

And Kandinsky came in

from the meadow one day

and, glancing at his easel,

shifted uneasily,

not quite knowing why.

It was at that moment

that modern art was born.

For on his canvas,

no bushes, no trees …

only colours and shapes

on his upside-down-placed canvas

and, if he had been

a flashy artist,

he would have jumped in the air

and turned somersaults.

But being severe and sober,

he merely coughed slightly

and smiled in a bemused way,

realizing that somehow he had

freed art from its subject,

by accident as it were;

shifted art toward music

by a mistake, and,

as he stared in wonder,

the bells rang out loud

from his canvas.

*

Phyllis Parham Reeve has written about local and personal history in her three solo books and in contributions to journals and multi-author publications, including the foreword to Charlotte Cameron’s play, October Ferries to Gabriola (Fictive Press, 2017). She is a contributing editor of the Dorchester Review and her writing appears occasionally in Amphora, the journal of the Alcuin Society. A retired librarian and bookseller and co-founder of the bookstore at Page’s Resort & Marina, she lives on Gabriola Island, where she continues to interfere in the cultural life of her community. More details than necessary may be found on her website.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “#763 Beach glass on a bed of seaweed”

This lovely review makes me realize those poor folks who keep reading and writing political commentary have only subjects who have rid their days of art in favour of wealth and power, then feel cheated because their subjects are so crude, and then wonder if life is worth living?

If only more people read books like On The Arts, not only would we have more interesting conversations, we might even vote for better politicians.

The meaning of life is to make things livable, not drain it as though it were a swamp.