#757 Carry on, Sasquatch

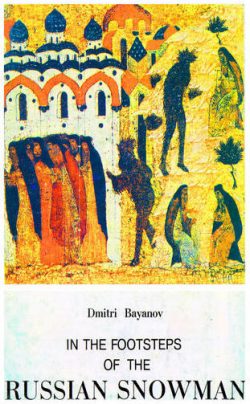

The Making of Hominology: A Science Whose Time has Come

by Dmitri Bayanov in association with Christopher Murphy, with a foreword by David Hancock and Jeff Meldrum

Surrey: Hancock House Publishing, 2019

$19.95 / 9780888390110

Reviewed by John Gellard

*

Have you ever seen a Sasquatch? Have you heard one, or smelled one? Have you ever seen a Sasquatch footprint, or met anyone who told you of a Sasquatch encounter? Have you ever thought about whether or not Sasquatches really exist?

Have you ever seen a Sasquatch? Have you heard one, or smelled one? Have you ever seen a Sasquatch footprint, or met anyone who told you of a Sasquatch encounter? Have you ever thought about whether or not Sasquatches really exist?

First of all, what are Sasquatches, exactly? They are usually described as humanoid, ape-like creatures, much larger than Homo Sapiens, covered with hair, broad shouldered and intimidatingly muscular. They have a powerful smell and they screech loudly. They live in mountainous, forested areas in the Pacific Northwest. In the United States they are called Bigfoots. Variations of the Sasquatch are encountered in remote areas across North America and throughout the world. There’s the Yeti in the Himalayas, for example, and the “hairy wild men” in Russia and Tajikistan.

But do they really exist? If they do, are they apes or humans? No-one has produced a so-called “type specimen” — a body dead or alive, or a skeleton, or a body part — and the scientific community is sceptical.

In The Making of Hominology, Dmitri Bayanov, a prominent Russian cryptobiologist and Christopher Murphy, a Canadian writer who has studied and written about the Sasquatch for many years, set out to show not only that the Sasquatch is a bona fide member of the genus Homo, a hominin, but also that the study of the Sasquatch, Hominology, is a legitimate branch of the science of Anthropology.

Now, here’s a caveat to the reader. The Making of Hominology is serious and thorough. It refers to the work of many scientists and experts, both supporters and sceptics. Analysis of data is detailed and precise, but you won’t find romantic, thrilling first hand stories of Sasquatch encounters. Therefore, you might want to approach the book already armed with a keen interest in the subject.

So, before you start on The Making of Hominology, you might read John Zada’s book In the Valleys of the Noble Beyond, a captivating collection of tales about Zada’s exploration of BC’s Great Bear Rain Forest “in search of the Sasquatch” (It’s reviewed by John Gellard in the Ormsby Review, #637 “Coastal Ranges and Riddles,” October 29, 2019). You’ll get thrilling personal tales of encounters. The book will lead you into the romance and mythology of Sasquatch lore and First Nations tradition. The trouble is that it will leave you there in “the land of serendipity, the ultimate landscape of myth, magic and metaphor.” You will be fascinated by the stories that will convince you that Sasquatches exist.

So, before you start on The Making of Hominology, you might read John Zada’s book In the Valleys of the Noble Beyond, a captivating collection of tales about Zada’s exploration of BC’s Great Bear Rain Forest “in search of the Sasquatch” (It’s reviewed by John Gellard in the Ormsby Review, #637 “Coastal Ranges and Riddles,” October 29, 2019). You’ll get thrilling personal tales of encounters. The book will lead you into the romance and mythology of Sasquatch lore and First Nations tradition. The trouble is that it will leave you there in “the land of serendipity, the ultimate landscape of myth, magic and metaphor.” You will be fascinated by the stories that will convince you that Sasquatches exist.

But now you need the scientific proof, and that’s what The Making of Hominology will give you.

There needs to be a “paradigm shift” following Thomas Kuhn’s analysis in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (University of Chicago Press, 1962). A paradigm is “a reigning dominant approach to solving problems in a given area of science.” A paradigm shift occurs when an unavoidable anomaly presents itself. For example, until the 1790s, when the problem of anomalous meteorites was solved, the paradigm was that rocks could not possibly fall from outer space. There had to be an earthly explanation, like volcanic eruptions. Then Peter Pallas discovered a 700 kg iron mass in Russia that the Tartars insisted fell from the sky. There was no other plausible explanation. The paradigm had to shift, and the science of meteoritics was born.

The pre-hominology paradigm among anthropologists was that two culture-bearing hominins –species of the genus Homo — could not exist at the same time. Recently the fossil record has shifted that paradigm. However, the prevailing wisdom remains that Homo Sapiens is the only hominin alive today.

The pre-hominology paradigm among anthropologists was that two culture-bearing hominins –species of the genus Homo — could not exist at the same time. Recently the fossil record has shifted that paradigm. However, the prevailing wisdom remains that Homo Sapiens is the only hominin alive today.

So where to go from here? In the absence of a type specimen, scientists are reluctant to be led down the garden path of possible errors and hoaxes which would make them look foolish.

We need an anomaly to shift the paradigm.

Ideally, we should get a type specimen. Should we hunt for a Sasquatch and kill it? Kathy Strain, an anthropologist, says: “I am pro-science, meaning I am pro-kill… since suitable habitat is dwindling.”

On the other hand the Bigfoot Field Research Organization’s policy is to study species in ways that will not harm them. Besides, what if Bigfoot turns out to be a bona fide hominin and not a great ape? That would be murder.

So are we stuck? Certainly not! On Friday, October 20, 1967, Roger Patterson and Bob Gimlin captured in one minute of 16mm film a female Bigfoot striding across a sand bar on Bluff Creek in Northern California.

Of course, the knee-jerk reaction among some scientists was to dismiss the film as a fake or an error. “Patterson and friends perpetrated a hoax…their Sasquatch was a large man in a poorly made monkey suit,” said Dr William Montagna, director of the Regional Primate Center at Beaverton, Oregon.

But not so fast! The film has been subjected to breathtakingly rigorous analysis and the weight is on the side of authenticity. “The Patterson-Gimlin film cannot be demonstrated to be a forgery at this time,” said Jeff Glickman, a forensic examiner with the North America Science Institute.

There is some discrepancy as to the height and weight of the subject because much depends on the speed of the film, which is uncertain. At 15 frames per second, Jeff Glickman estimated these measurements:

Height: 7 ft, 3.5 inches

Weight: 1,957 pounds

Arm length: 43 inches

Leg length: 40 inches.

D.W. Grieve, reader in biomechanics at the Royal Free Hospital School of Medicine, assumes a 24 fps speed. His estimates are rather smaller, but still those of an exceptionally large Homo Sapiens:

Height: 6 ft, 5 inches

Weight: 280 pounds.

But, says Dr Grieve, “the possibility of faking is ruled out if the speed was 16 or 18 fps”, the most probable speed.

The Patterson-Gimlin film, then, is not a fake. Now the question is: What kind of being is seen in the film? Human or ape? Hominin or pongin? If it’s an ape, then we’ve shifted the paradigm that says there are no great apes in North America. If it’s a primitive human, we have an opportunity for greater insights into human evolution. Either way, the film “broke through the barriers of preconceived scientific notions…We can thank Roger Patterson and Bob Gimlin for providing us with an enduring mystery that has become a great source of pleasure and intrigue for many, many people.” Is the film enough to force a paradigm shift and make Hominology an accepted branch of the science of Anthropology? Probably. Time will tell.

Another wellspring of information about the Sasquatch is the enormous number of footprints that have been observed, photographed and cast in plaster. In the American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Dr D. Jeffrey Meldrum reports examining over 100 plaster casts and 50 photographs, some of which were gathered at the site of the P-G film. The Sasquatch foot is quite different from the human foot. It is flat, and shows pronounced flexibility in the mid-tarsal joint. The heel impression is absent. These features are consistent with the observed gait of the Sasquatch. “It seemed to glide or float as it moved.” This is in marked contrast to the human “stiff-legged striding gait with the distinct heel-strike and toe-off phases.” The Sasquatch’s flat flexible foot with the long toes seems well adapted to the mountainous rugged terrain of the Pacific Northwest.

The authors give examples of plaster casts, with measurements. Sasquatch feet are much longer and broader than human feet. The samples range from 13 inches to 18.5 inches long. They include a “cripple foot” cast of a deformed right foot. Dr Grover Krantz reasons that if the footprints were a hoax, the hoaxer had to have an in-depth knowledge of anatomy (A Scientific Inquiry into the Reality of Sasquatch, Johnson Printing, Boulder, CO, 1992).

Christopher Murphy rests his case on a “call to action.” The objective is to have Hominology recognized as a valid scientific discipline. There is lots of interest. Google “Bigfoot” and you’ll get 24,600,000 hits, but they are largely hoaxes, making the Sasquatch an object of entertainment.

A major step in the right direction is the establishment of the Relict Hominoid Inquiry at Idaho State University. That website has proper scientific credentials. What is needed, though, is “a formal international society for research in Hominology.”

The book is endorsed, among others, by Jane Goodall, PhD, DBE; Founder of The Jane Goodall Institute, and renowned authority on primates. “A lifetime of scholarly examination of the [hominid] question with evidence spanning from the dawn of written communication to the present has culminated in this important book — The Making of Hominology.”

“Most certainly,” says Murphy, “at this juncture, the main thing to do is to get The Making of Hominology out to major scientific organizations and universities and thereby put the case on the table.”

Yes, read the book, and help it make a major step in the understanding of Homo Sapiens and of our companions on Planet Earth.

*

John Gellard spent his childhood in England and Trinidad, donated his adolescence to an English boarding school, earned an MA in Philosophy from the University of Western Ontario, and taught English and Drama in London, Ontario, for seven years. In 1973, he arrived in the West Kootenay where he felled and peeled pine logs on his “wild land” property and built a log cabin. Gravitating to the city, he taught for thirty years at Vancouver Technical Secondary School and Kitsilano Secondary. He still helps run writing workshops for students, notably (since 1993) an annual overnight retreat on Gambier Island. His articles have appeared in the Globe and Mail and the Watershed Sentinel. He takes an active interest in environmental issues and travels extensively in B.C. He lives among friends in Kitsilano and on Hornby Island, has two grown sons, and retired from teaching English and Writing at Kitsilano Secondary School after being named Canada’s “Best High School Teacher” in a Maclean’s poll in August 2005.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster