#748 Collishaw of the western desert

Flying to Victory: Raymond Collishaw and the Western Desert Campaign, 1940-1941

by Mike Bechthold

Norman, Oklahoma: Oklahoma University Press, 2017

$34.95 (U.S.) / 9780806155968

Reviewed by John Hinde

*

In his recent book, Flying to Victory: Raymond Collishaw and the Western Desert Campaign, 1940-1941, Mike Bechthold points out that “May 1941 marked a pivotal transitional month for British forces in the Mediterranean theater” (p. 162). The spring of 1941 was indeed a dire time for the British during the Second World War. “Disaster seemed to follow on disaster,” (p. 145), thought Air Commodore Raymond Collishaw, the operational commander of the Royal Air Force’s Desert Air Force. Despite surviving the German onslaught during the Battle of Britain of the summer and autumn of 1940 and successfully driving the Italians out of Egypt at the end of the year, conquering much of Libya in the process, British and Imperial troops suffered a series of defeats which threatened its strategic control of the Mediterranean and Egypt and subsequently Britain’s continued war effort. At the end of March 1941, Erwin Rommel, commander of the Deutsches Afrika Korps, launched his first offensive against Allied forces, driving them out of the Libyan province of Cyrenaica, besieging the important Mediterranean port of Tobruk, and threatening Egypt and the Suez Canal. This was soon followed by British defeat in Greece after the German invasion of 6 April, and a few weeks later by the disastrous evacuation of Crete. To top things off, Operation Battleaxe, the June 1941 campaign designed to expel the Germans and Italians from eastern Cyrenaica and to relieve the siege of Torbuk, ended in failure. Winston Churchill’s disappointment and frustration were such that he sacked the Commander in Chief, General Sir Archibald Wavell.

In his recent book, Flying to Victory: Raymond Collishaw and the Western Desert Campaign, 1940-1941, Mike Bechthold points out that “May 1941 marked a pivotal transitional month for British forces in the Mediterranean theater” (p. 162). The spring of 1941 was indeed a dire time for the British during the Second World War. “Disaster seemed to follow on disaster,” (p. 145), thought Air Commodore Raymond Collishaw, the operational commander of the Royal Air Force’s Desert Air Force. Despite surviving the German onslaught during the Battle of Britain of the summer and autumn of 1940 and successfully driving the Italians out of Egypt at the end of the year, conquering much of Libya in the process, British and Imperial troops suffered a series of defeats which threatened its strategic control of the Mediterranean and Egypt and subsequently Britain’s continued war effort. At the end of March 1941, Erwin Rommel, commander of the Deutsches Afrika Korps, launched his first offensive against Allied forces, driving them out of the Libyan province of Cyrenaica, besieging the important Mediterranean port of Tobruk, and threatening Egypt and the Suez Canal. This was soon followed by British defeat in Greece after the German invasion of 6 April, and a few weeks later by the disastrous evacuation of Crete. To top things off, Operation Battleaxe, the June 1941 campaign designed to expel the Germans and Italians from eastern Cyrenaica and to relieve the siege of Torbuk, ended in failure. Winston Churchill’s disappointment and frustration were such that he sacked the Commander in Chief, General Sir Archibald Wavell.

These were unexpected reversal of fortunes, coming as they did so quickly on the heels of Britain’s first successful campaign of the war, Operation Compass, the expulsion of the Italians from Egypt and the conquest of Cyrenaica. This was an impressive victory, although it has unfortunately been downplayed because it was a victory over allegedly inferior Italian forces. As Bechthold points out, however, “the results far exceeded even the most optimistic forecasts made prior to the campaign [Compass] …. What started on 9 December 1940 as a limited five-day offensive to capture a series of Italian camps in Egypt ended up with the fall of Benghazi and the complete destruction of the Italian Tenth Army at Beda Fromm less than two months later, sealing an improbable victory” (p. 122).

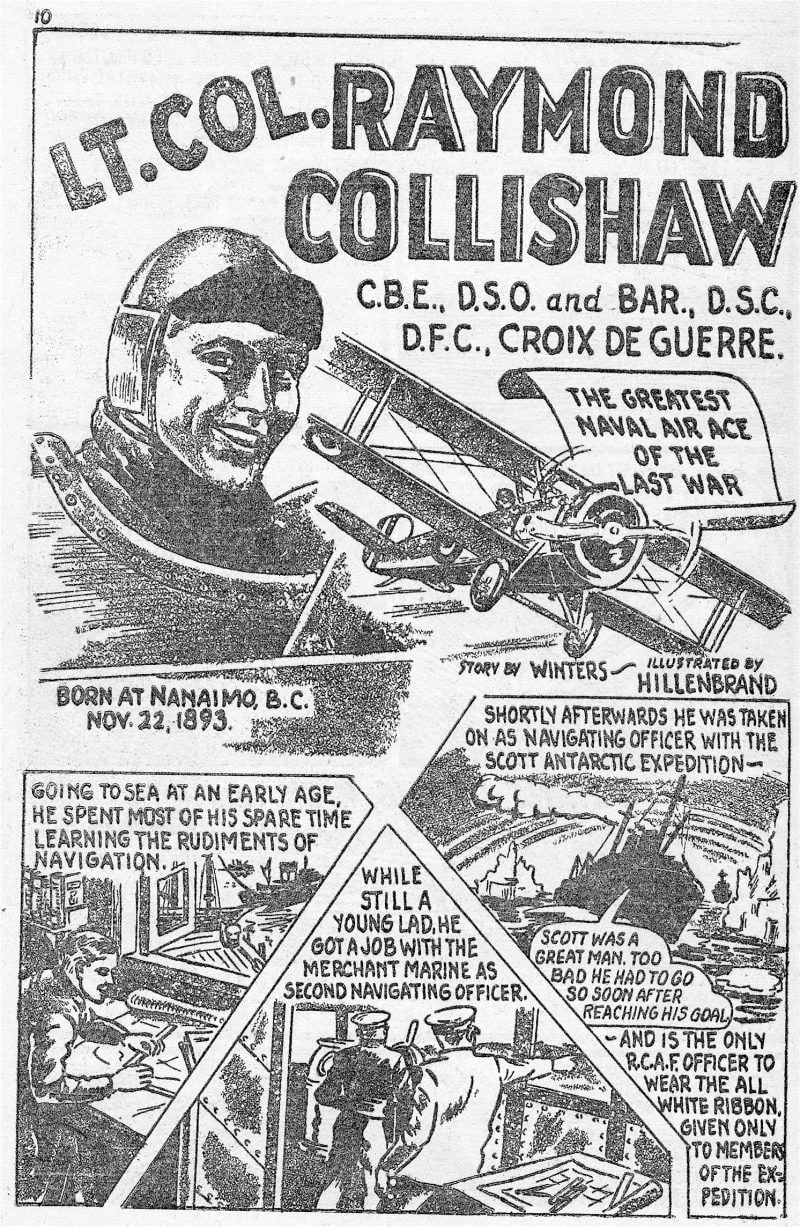

A key figure in this “improbable victory” was a man well-known to British Columbians, especially those living on central Vancouver Island: Raymond Collishaw (1893-1976), after whom Nanaimo’s airport is named. The Nanaimo-born Collishaw is best remembered as one of the leading air aces of the First World War, scoring an impressive 61 confirmed kills as a pilot with the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) and the RAF. He was the second highest Canadian ace after the more celebrated Billy Bishop, who had 72 kills, and the sixth highest scoring ace of all belligerent nations during the war. However, Air Commodore Collishaw’s contribution to the Allied war effort during the Second World War was equally as impressive if much less well-known. As the commander of the RAF’s 202 Group in Egypt, Collishaw was responsible for air operations during the early years of the Western Desert Campaign. In particular, his effective use of the very limited air power available to the British in North Africa was not only a decisive factor in the success of Operation Compass. More significantly, Collishaw developed and implemented an innovative system of close air support (CAS), or tactical air power, which was eventually adopted by the RAF and USAAF and which made a major contribution to the defeat of the Germans in 1945.

As Mike Bechthold points out in this important book, there was no agreement in the RAF about the best use of air power in wartime. While the Battle of Britain had revealed the importance of fighter aircraft operating as part of a broader defensive system, the RAF firmly believed that it also had an offensive role to play, hence its determination to develop a heavy strategic bomber force capable of bringing the war to the Germans. Indeed, many believed the strategic bombing campaign would be the decisive weapon of the war.

This was not the only offensive potential of air power, however. Close air support, which Collishaw had helped develop during the First World War, is the use of aircraft to attack ground targets during land campaigns. How best to deploy air power for this task had been the subject of intense debate within the RAF and between the RAF and the army, a debate which intensified dramatically during Collishaw’s time in North Africa. In a nutshell, the army believed that air power should be used to protect troops from enemy air attack and, like artillery, to attack enemy troops and armour. In sharp contrast, Collishaw maintained that air power was best employed to destroy the enemy’s air force in order to achieve air superiority and then to attack “targets beyond the enemy’s battle space” (p. 38). Attacking supply depots, airfields, and lines of communication would reduce the enemy’s ability to resupply its troops, erode morale, and force its air force to adopt a defensive posture as it would be obliged now to defend the rear areas, rather than mount its own offensive operations.

Collishaw’s success with this approach during Operation Compass was nothing less than remarkable. Despite a chronic lack of resources and obsolete aircraft (initially the Desert Air Force had only one modern Hawker Hurricane, known affectionately as “Collie’s battleship”), the RAF effectively suppressed the more numerous Italian air force, disrupting its ability to fight, and pounded away at Italian bases, supply depots, communication lines and ports. Italian ground forces faced a logistical crisis and had to operate without air cover. Despite this impressive achievement, Collishaw’s future as commander was far from secure. He was criticized for being too aggressive and wastefulness of scarce resources, a claim Bechthold persuasively rejects. When, following the string of defeats in 1941, Air Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder became commander of the RAF in the Middle East, criticism of Collishaw mounted. For reasons that are not entirely clear, Tedder did not like Collishaw and was looking for reasons to sack him, especially in the wake of Rommel’s spring offensive, when relations between the RAF and the army deteriorated dramatically. The British were desperately weakened by the transfer of ground and air forces for the defence of Greece and Rommel quickly erased their earlier gains. Furthermore, during Operation Battleaxe, the army insisted over the objections of RAF commanders that the limited air assets be used defensively to protect troops. Although this use of air power was quickly recognized as futile, the RAF was blamed by Wavell for the defeat and was criticized for its alleged inadequate defence of Crete, despite that island being at the very edge of the RAF’s operational range. Wags in the army commented that the RAF really stood for “Rare as Fairies” and “Royal Absent Force.”

After Battleaxe, Collishaw’s days were numbered. On 10 July 1941 Tedder relieved him of his duties, arguing that Collishaw was “played out” and “not the right man to tackle the Hun and the [British] Army” (p. 187). Despite his air doctrine being vindicated by none other than Churchill, over objections of the Army, Collishaw held only a series of minor posts after his return to Britain, and on 15 July 1943, the now Air Vice Marshal left the RAF. His retirement remains a mystery. He claimed in his memoirs only that “I was retired,” but why would a successful commander in his prime — he was not even fifty years of age — not continue to serve. As Bechthold suggests, it really is impossible to know, but Tedder’s hostility towards Collishaw perhaps points to the obvious answer. Regarding him as a “bull-headed, unimaginative cuss” (p. 205), the quiet, reserved Tedder clearly objected to Collishaw’s more boisterous, enthusiastic, and companionable personality. “Tedder did not trust or respect Collishaw and wanted him gone” (p. 206).

Mike Bechthold’s Flying to Victory is a very welcome addition. It is a pleasure to read, is exhaustively researched, and it makes important contributions in a number of key areas that have been neglected by historians. First, his detailed and lively analysis of Operation Compass and the failure of Battleaxe fills important gaps in our knowledge, especially with regards to the use of air power in these campaigns. Second, the history of tactical air power and doctrine during the Second World War has not received much attention, perhaps because it lacks the glamour of Fighter Command or the sheer destructive force of strategic bombing (and the controversies surrounding it). During Operation Compass, Collishaw and the DAF developed the most effective use of tactical air power, creating a meaningful and effective use of limited RAF assets that contributed greatly to Allied victory. Collishaw essentially established the basic principles of CAS and applied them with considerable success with very limited resources.

Last but by no means least, Raymond Collishaw has finally received his due. The prevailing view of Collishaw’s role in North Africa was largely shaped by Tedder’s personal animosity, one reason perhaps why Collishaw has not received the recognition he deserves. Yet, as Bechthold demonstrates, Collishaw was a very successful commander who was well-liked by his subordinates. Although his forced retirement remains shrouded in mystery, it is clear that he made a significant contribution to Allied victory not just on the Western Front in the First World War but in the Western Desert during the Second.

*

John Hinde teaches history at Vancouver Island University. He is the author of Jacob Burckhardt and the Crisis of Modernity (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2000) and When Coal Was King: Ladysmith and the Coal-Mining Industry on Vancouver Island (UBC Press, 2003).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#748 Collishaw of the western desert”