#721 Five British Columbia battalions

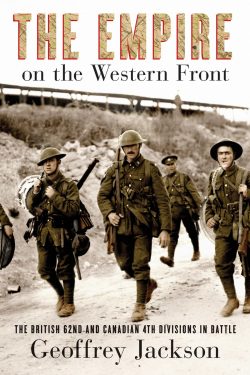

The Empire on the Western Front: The British 62nd and Canadian 4th Divisions in Battle

by Geoffrey Jackson

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2019

$34.95 / 9780774860154

Reviewed by James D. Barrett

*

Geoffrey Jackson’s readable study of the performance of the 62nd Division British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and the 4th Canadian Division (CEF) hits the mark with a detailed analysis and comparison between these two new divisions that were raised mid-war and first saw service at the Battle of the Somme in late 1916. The 4th Canadian Division comprised sixteen infantry battalions, of which five were from BC: the 47th (British Columbia) Battalion Canadian Infantry, based in New Westminster; the 54th (Kootenay) Battalion Canadian Infantry, based in Nelson; the 67th (Western Scot) Pioneer Battalion Canadian Infantry, based in Victoria; the 72nd Battalion (Seaforth Highlanders of Canada), based in Vancouver; and the 102nd (North British Columbia) Battalion Canadian Infantry, mobilized in Comox.

Geoffrey Jackson’s readable study of the performance of the 62nd Division British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and the 4th Canadian Division (CEF) hits the mark with a detailed analysis and comparison between these two new divisions that were raised mid-war and first saw service at the Battle of the Somme in late 1916. The 4th Canadian Division comprised sixteen infantry battalions, of which five were from BC: the 47th (British Columbia) Battalion Canadian Infantry, based in New Westminster; the 54th (Kootenay) Battalion Canadian Infantry, based in Nelson; the 67th (Western Scot) Pioneer Battalion Canadian Infantry, based in Victoria; the 72nd Battalion (Seaforth Highlanders of Canada), based in Vancouver; and the 102nd (North British Columbia) Battalion Canadian Infantry, mobilized in Comox.

The senior leadership from the divisional commanders down to the battalion commanding officers of both organisations generally had some prior military experience and in many cases active service in 1914-15. A good example was Lt-Col Jack (John Weightman) Warden, Commanding Officer of the 102nd (North British Columbia) CEF, who was wounded at the 2nd Battle of Ypres at St Julien with the 7th (British Columbia) CEF, recovered from his wounds, received command of his battalion in Canada, and returned to action with the 4th Canadian Division in 1916.

By 1916, the majority of the remaining junior officers and soldiers were recruits without any prior military training. Jackson’s study compares the experiences of both divisions on how they were raised and trained, and their “learning curves” following their arrival on the battlefields, followed by the impact of both on their combat performance from late 1916 to the signing of the Armistice on 11 November, 1918. He does this very well, through telling the stories of each unit and highlighting both their successes and challenges.

Jackson does not miss the communication issues that senior commanders had to deal with in the Great War, where up-to-date battle information from the front lines to rear headquarters was negligible once action had been joined. Although both Division and Brigade Commanders often went forward to ascertain progress, there was little they could do to influence success outside of sound staff work, planning, and effective employment of resources, especially the artillery.

Particularly challenging was to know when to shut down offensive operations. Combined with the difficulties experienced by the infantry in attempting to advance behind barrages that could not easily be adjusted to the changing situation on the battlefield, Jackson understands the difficulty of extending coverage for the infantry advance by the artillery beyond the initial ranges experienced at the start of the action, and especially the ratio of increased casualties for diminished gain when artillery support was lacking. Subsequently, he covers the development of the “bite and hold” tactics of 1917-18.

Jackson does not miss the increasing autonomy of the Expeditionary Forces and the reductions of strength in the BEF Units in 1918, which did not occur in the Canadian Corps. These reductions in fact eliminated its 5th Division in Britain, which decreased both its overall strength and firepower effectiveness as “shock troops.”

In his sound analysis of the growth of these two comparable units, Jackson notes the evolution of training within the BEF as well as the evolution of combat tactics by the Commonwealth Forces. By 1918, the BEF had devolved much forward leadership down to the platoon and section levels with an increase in firepower up front through more Lewis Machine Guns carried at the section level and the forward deployment of heavy machine gun assets for immediate fire coverage behind the artillery barrage. It is pleasant to see Jackson’s acknowledgement of the fact that the British General Staff were using their lessons learned from 1916, with the assistance of the development of the tank and artillery improvements, to develop tactics that would lead to further successes in 1917 and ultimately to the last “100 Days” and the defeat of Germany. By 1918, both the 62nd and 4th Canadian Divisions were clearly up to par with their predecessors on the battlefield.

I did, however, have a few minor quibbles. Lt-Col Warden’s last name is misspelled as Worden (p. 17). In his Battle of the Somme coverage, Jackson blames the artillery for not clearing wire effectively. This is quite true within the artillery’s restrictions of 1916 in trying to destroy German wire using ground penetrating, aerial, and shrapnel shell bursts. They were simply not as effective as the later shells, as seen when the British Mark IV Shell Fuse came into service in 1917. Shells now exploded on the slightest touch of the wire: a very effective improvement.

Finally, I would like to have seen more detail on the actual small party tactics developed from 1916 onwards, especially on how the platoon and section elements were reorganized with a view to survivability of the leadership and the extra use of firepower with the addition of the Lewis Light Machine Guns. The late Desmond Morton gave a very good lecture to our class in detail on this very subject when I was attending Staff College in Kingston in 1998. This is perhaps something to be explored in a future edition, and in no way takes away from the work Jackson has done here.

Geoffrey Jackson is to be congratulated for his efforts. The Empire on the Western Front is recommended reading for anyone interested in Great War history.

*

Major James D. Barrett, CD is a graduate of UBC Faculty of Education (Secondary) 1979 majoring in English and Social Studies (History & Geography). He joined the Canadian Armed Forces in 1982 as a member of The BC Regiment (Duke of Connaught’s Own), an Armoured Reconnaissance Regiment that perpetuates the history of the 7th Bn, 29th Bn and 102nd Battalions CEF. A graduate of the Canadian Forces Staff College (Kingston) in 1998, he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel and commanded 15th Field Artillery Regiment RCA from 2007 to 2011. He retired as the Assistant Chief of Staff 39 Canadian Brigade Group Headquarters in 2013. In 2014, he returned to duty as a General Service Officer with the Cadet Organization Administrative and Training System and currently in the rank of Major commands 3300 BCR Cadet Corps in Surrey. In the summer months he resumes his former rank as LCol and commands the Rocky Mountain Cadet Training Centre in Alberta. He writes a quarterly history article for the BC Regiment’s Newsletter, The Duke, and is a Director of the BC Regimental Association and Museum Societies. He is the Chair of the Board of Directors for the BC (Mainland) Military Family Resource Centre.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster