#700 The university of Point Grey

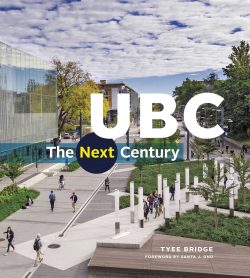

UBC: The Next Century

by Tyee Bridge, with a foreword by Santa J. Ono

Vancouver: Figure 1 Publishing, 2019

$40.00 / 9781773270883

Reviewed by Herbert Rosengarten

*

From the beginning the University of British Columbia (UBC) has nurtured ambitions of greatness. Its potential was recognized by BC’s premier, Sir Richard McBride, who sent his congratulations upon the University’s opening in September 1915, and noted that BC now possessed “an institution that will some day rank with the great Universities of the Continent.” Given that at the time the new university was housed in a cluster of temporary buildings beside the Vancouver General Hospital, and counted a student complement of 379, this was an expression of faith indeed. But even McBride could not have foreseen how fully that hopeful vision would be realized over the century that followed.

From the beginning the University of British Columbia (UBC) has nurtured ambitions of greatness. Its potential was recognized by BC’s premier, Sir Richard McBride, who sent his congratulations upon the University’s opening in September 1915, and noted that BC now possessed “an institution that will some day rank with the great Universities of the Continent.” Given that at the time the new university was housed in a cluster of temporary buildings beside the Vancouver General Hospital, and counted a student complement of 379, this was an expression of faith indeed. But even McBride could not have foreseen how fully that hopeful vision would be realized over the century that followed.

The numbers alone tell much of the story: UBC today enrolls 65,000 students on two campuses (Point Grey and Kelowna); it is home to 17,000 faculty and staff; among current or former faculty and alumni it boasts eight Nobel Prize winners; and it runs on a budget of almost $3 billion annually. Among Canada’s 15 public research universities UBC outperforms all except the University of Toronto in its success in attracting research funding. UBC Thunderbird teams have won more national championships than any other Canadian university, and their success even extends into the US realm — UBC won its fifth NAIA women’s golf championship in the spring of 2019.

This is the story Tyee Bridge sets out to tell in UBC: The Next Century. As his title proclaims, he has not produced a history of the University: the book is very deliberately a record of the university of today, and while it acknowledges past achievements, it also looks ahead. In his preface, President Santa Ono speaks of education as a catalyst, a force inspiring change, and describes the book that follows as an account of “the pathways we are making into the future.”

The result is a well-crafted and well-illustrated overview of a modern North American university. The book is divided into sections covering teaching and learning, campus life, research and innovation, sports and recreation, culture and the humanities, and sustainability. Within each section we’re presented with snapshots of the programs, buildings, people, and achievements that have enabled UBC consistently to rank among the top fifty universities in the world.

Of necessity such an approach imposes limits on what the author can include. In the chapter on teaching and learning, for example, Bridge paints with a very broad brush, providing tantalizingly brief accounts of just a few of the 150 or so faculties, schools, and departments at UBC Vancouver and UBC Okanagan, not to mention the multitude of programs, institutes, and research centres that have proliferated in recent years. Many of the units he chooses to describe have a strong public presence beyond the groves of academe — Theatre & Film, the School of Music, and the School of Journalism, for example, where performance and publication bring students into direct contact with the world outside the classroom.

Throughout, Bridge stresses the outward-facing modernity that increasingly characterizes our universities today: their readiness to experiment with new technologies, their investment in innovation and applied research, and their eagerness to collaborate with industry, business, and government. UBC stands at the forefront of scientific and medical innovation in a number of fields, and Bridge gives telling accounts of UBC’s research successes in such areas as astrophysics, genetics, big data, cancer treatments, brain disorders, and quantum materials. At times these descriptions read a little like web-page promos, but Bridge keeps the reader’s interest by limiting institutional hyperbole and introducing the human element through short bios of alumni whose success in their chosen fields attests to the quality of the learning and research carried out at UBC.

A recurring motif throughout the book is the University’s growing embrace of Indigeneity. UBC Vancouver stands on the traditional and unceded territory of the Musqueam Indian Band, and in recent years the University and the Musqueam have developed a fruitful and empowering relationship, a connection accelerated and enhanced by the process of reconciliation following the findings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. A similar spirit of collaboration exists in the Okanagan: when UBC opened its campus in Kelowna in 2005, it was formally welcomed by the Syilx Okanagan Nation, and entered into an agreement with local First Nations to work together on educational programs. The agreement was renewed on the occasion of UBC Okanagan’s tenth anniversary.

Bridge recognizes the significance of these developments: they reflect the growing importance the University attaches to a strong relationship with its Indigenous neighbours. He touches on the Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre, and the Reconciliation Pole carved by Haida hereditary chief James Hart: telling reminders of a dark side of Canada’s history. Indigeneity is not an add-on at UBC; Bridge shows that it’s woven into many aspects of campus life, and is becoming part of the University’s sense of its own identity.

Tyee Bridge ends his tour of UBC with an account of the University’s impressive contributions to sustainability, a concept that UBC has applied to itself in very practical terms by becoming a “living lab” in which new approaches to conservation, food production, and energy can be put to the test in a controlled environment. The Beaty Biodiversity Museum, Tallwood House, the Greenheart TreeWalk, the UBC Farm — these are only the most visible expressions of an extensive network of research labs and academic programs that have made UBC a world leader in this area: as Bridge tells us, “in 2019 Times Higher Education ranked UBC as the number-one university in the world for taking action to fight climate change and its impacts.”

As that last observation makes clear, UBC: The Next Century is unapologetically a celebration, a firework display that sets out to dazzle and impress its readers with its portrait of a youthful, vigorous, forward-looking institution. This is not the place to look for accounts of the problems plaguing every university today: issues such as funding shortages, right-and left-wing activism, corporate influence, or conflicts around racism and sexism. UBC has its share of these and other challenges; but Bridge has stepped around such matters to focus on those elements that bring thousands of new students to UBC each year, drawn by its promise of a unique and exciting educational experience. This book will surely heighten that expectation.

*

Herbert Rosengarten taught in the English Department at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver for many years, then switched to administration as Executive Director of the UBC President’s Office until his retirement. His publications include several literature anthologies and a history of UBC, co-written with Eric Damer: UBC: The First 100 Years (UBC, 2009). He edited or co-edited a number of the Brontë novels – Villette, Shirley, The Professor, and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall — for Oxford University Press, and contributed to The Oxford Companion to the Brontës (2003). His most recent publication is a chapter on Charlotte Brontë’s novel Shirley in Time, Space, and Place in Charlotte Brontë, ed. Hoeveler and Morse (Routledge, 2017). He is Past President and Program Chair of the Vancouver Institute, and chairs the Legacy Project, which gathers materials about the history of UBC in the form of video interviews, books, and other memorabilia. In 2016 he received the Honorary Alumnus Award from the UBC Alumni Association.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster