#684 English views & melting glaciers

Rail

by Miranda Pearson

Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queens University Press, 2019

$17.95 / 9780773558946

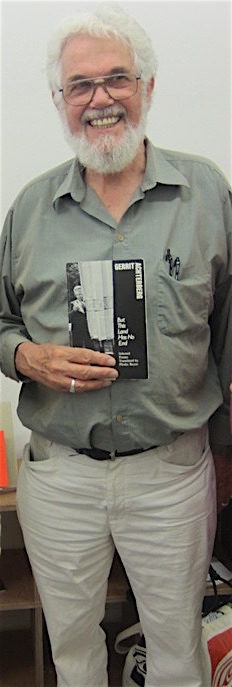

Reviewed by Christopher Levenson

*

If surprise is a necessary ingredient of good poetry, Miranda Pearson’s fifth volume, Rail, will not disappoint. Those who know her four previous volumes — Prime, The Aviary, Harbour, and The Fire Extinguisher — will recognize familiar virtues. One is a keen awareness and exploitation of the sounds of words, an aspect neglected in much contemporary Canadian poetry. Thus, in “Trail closed for winter,” we are warned to:

If surprise is a necessary ingredient of good poetry, Miranda Pearson’s fifth volume, Rail, will not disappoint. Those who know her four previous volumes — Prime, The Aviary, Harbour, and The Fire Extinguisher — will recognize familiar virtues. One is a keen awareness and exploitation of the sounds of words, an aspect neglected in much contemporary Canadian poetry. Thus, in “Trail closed for winter,” we are warned to:

Avoid the seeping, glossy,

the thaw-busy. Blue flow stitched

and flickering in floe, like minnow

or stretch-marks

Another is the accuracy of her visual detail. In the first poem, “Camber Sands,” speaking of her father’s photography, she writes “He taught me to observe,” something she illustrates in “Inside the cornfield,” where she evokes “bundled rows of blond bead-hybrid / of mouth organ and abacus.” Sometimes, as in “Bones,” it seems simply a matter of giving free rein to a fertile imagination that sees:

Bone as fence, bone as instrument

Eye sockets large as satellite dishes knuckle

the Toronto sky, solid frill around the collar-stone Tudor ruff

or petals on an anemone

While the same effervescent visual awareness informs her poems about Degas and Modigliani, in “Paint Box” she consciously links the two arts:

Painting grows out of poetry

as green will fork from a tree

and the adult emerge from the child —

though our eyes remain the same.

As the range of themes and subject matter makes clear, she has lost none of her omnivorous curiosity.

What is different, for me at least, is that these poems seem to be linked less by theme or setting than by a pervasive mood, mostly an off-season, autumnal, or wintry one, and they are suffused with uncertainty. Pearson’s often bleak English landscapes, such as “Whitby in the rain,” are matched by poignant poems, such as “Driving Instructions” and “Stroke,” that focus on her mother’s stroke.

But maybe I exaggerate, for even in “The Frieze,” one of a moving sequence of poems that deal with dyscalculia, the inability to understand numbers, her observations are tempered by a sense of playfulness, irreverence, and the incongruous, as evident in “The Hunter” where, going through her mother’s clothes, she discovers:

Pie-crust collars, frilled sleeves —

all blessed by Diana, Patron Saint of Wardrobe.

A row of dusty handbags looks abashed and lopsided,

as if they all had strokes.

Pearson has a good ear too for sardonic overtones, as in these lines in “The Frieze” that evoke the number six:

This one has a tummy pain and is sitting down.

Perhaps it’s getting old or having a baby

Or praying repentant and kneeling like Henry’s wives.

Perhaps some of this quality she inherited from her mother, who is quoted as saying:

You have to see the funny side.

You have to keep dancing, keep leaping like the salmon,

the deer, the lamb.

A visit with a female friend to Sylvia Plath’s grave results in a similar urge to vitalism in the injunction of its last line “Live, girls, live.”

But then, eschewing the whimsical. Pearson is rarely less than bracingly tactile and direct, not least about the ordinary miracle of the human body, of which she asks “What of the held weight of a human lover, what of touch?” For, as she recognizes in “Alaskan Cruise,” “we are all animals, basic and social.”

At its most compelling, this determination to be true to the physical world blends with a kindred quality, a sense of appreciation and gratitude for things as they are, whether, as in “Visiting our grandparents,” it is a glimpse of mediaeval sculpture or the sense Pearson evokes in “Bowl” of total involvement in the creation of pottery:

We forget our bodies, forget gender —

Though craft’s a feminine, subordinate term

for this involved physicality and ritual.

Clay forgives

but has its own soft memory

and when you handle it, it lives

Like all good poets, Pearson draws attention not only to details, situations, or states of being we might otherwise have overlooked, but also makes valuable distinctions, sometimes just in passing, as in “silence not of regret/ but of listening.” But at a macro-level, as in “Alaskan Cruise,” her engaged mind neatly juxtaposes on the one hand the “eleven layers of romance” and the “ice porn” of melting glaciers, and points up the relationship between the glacier “that slumps in on itself/ a grieving in blue and white” and the “broken turquoise tiles of Istanbul,” so that we understand the over-arching significance of the final lines: “Fuel from the ship unravelling into the water, /a spooling thread/ casually inscribes/ a future.”

Overall, whether dealing with intimate human relations or with the beloved natural world, Rail is a worthy addition to Pearson’s already impressive oeuvre.

*

Born London, England 1934, Christopher Levenson came to Canada 1968 and taught English, Creative Writing, and Comparative Literature at Carleton University from 1968 to 1999. He has also lived and worked in the Netherlands, Germany, Russia, and India. He has written twelve books of poetry, the most recent of which is A tattered coat upon a stick (Quattro Books, 2017). He co-founded Arc magazine in 1978, was its editor for the first ten years, and was for five years Series Editor of the Harbinger imprint of Carleton University Press, which published exclusively first books of poetry. He has reviewed widely, mostly poetry and South Asian literature in English, in the UK and Canada. With his wife, Oonagh Berry, Christopher moved to Vancouver in 2007 where he helped re-start and run the Dead Poets Reading Series.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Comments are closed.