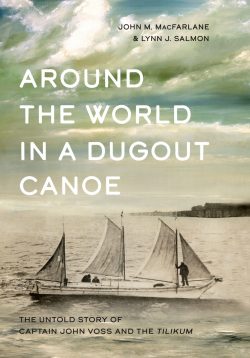

#667 Canoeing to London

Around the World in a Dugout Canoe

by John M. MacFarlane and Lynn J. Salmon

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2019

$29.95 / 9781550178791

Reviewed by Mark Forsythe

*

There is nothing more enticing, disenchanting, and enslaving than the life at sea — Joseph Conrad

There is nothing more enticing, disenchanting, and enslaving than the life at sea — Joseph Conrad

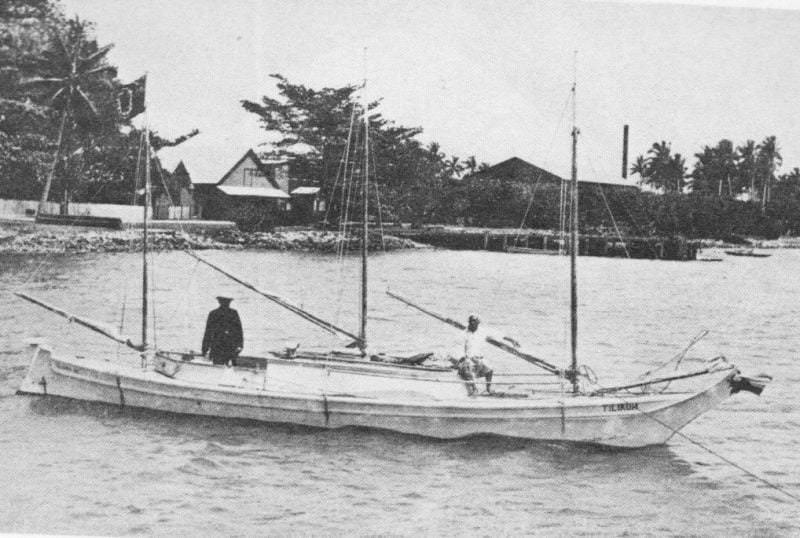

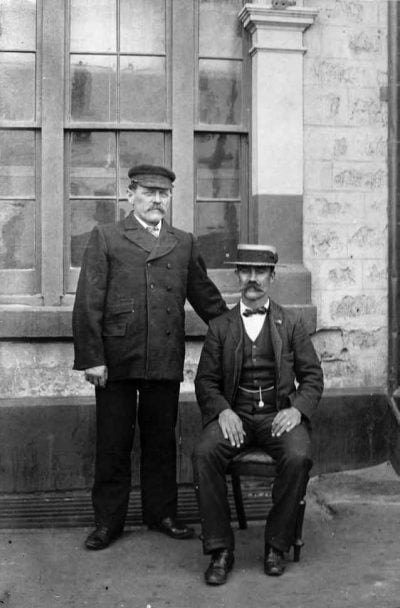

The Tilikum is legendary in B.C.’s maritime history, and her captain the subject of much speculation and myth-making. John Voss set sail from Oak Bay in 1901 with a young newspaper reporter (with no sailing experience) as mate. Norman Luxton also owned one half of the converted Nuu-chah-nulth canoe, but after 58 grueling days on the Pacific he packed it in. Captain Voss continued his quest to circumnavigate the globe in the smallest craft ever, inspired by Nova Scotia-born Joshua Slocum, who successfully sailed solo around the world aboard Spray. His account, Sailing Alone Around the World (published in 1900) launched the dreams of enough sailors to fill a bluewater fleet. It continues to do so.

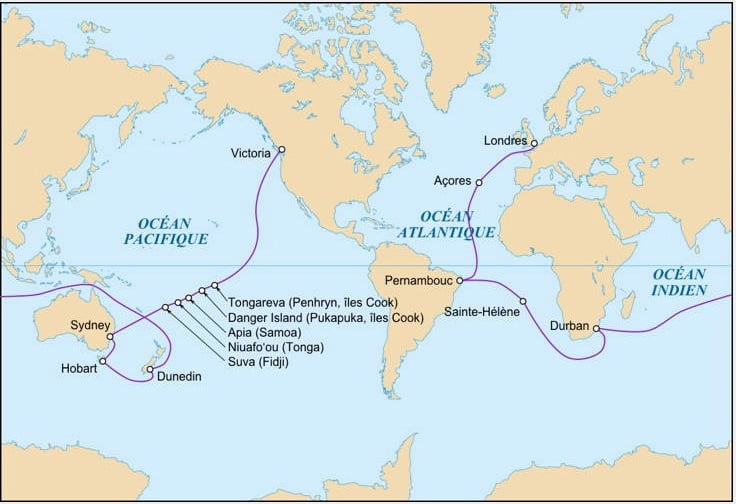

At 38 feet, Tilikum was smaller than a ship’s lifeboat; its deck not quite 14 inches from the water. Many thought Voss’s plan to sail the globe crazy. “My proposition was jeered at not only by lands men but experienced sea faring men and after inspection of my boat it was the general expression that I would never return.” Voss and a succession of mates survived storms, illness, mouldy bread, and breaking waves able to swamp Tilikum and everything on board. The mate who replaced Luxton was washed overboard in the Pacific, never to be seen again. Captain Voss eventually sailed Tilikum onto the Thames River at London, 40,000 miles and three and a half years after setting sail. Although he didn’t return sail the vessel to Victoria, he did cross three major oceans in a tiny canoe rigged with sails — a remarkable achievement by any measure.

There are significant inconsistencies in accounts of the journey written by Voss and Luxton, right from the moment they departed. Voss wrote that hundreds waved them off, Luxton claimed it was a handful of friends and family. Photos would appear to confirm this. Over the last century, Voss’s exploits have become foggy, a confusion of fact and fiction. John MacFarlane and Lynn Salmon attempt to set the record straight in Around the World in a Dugout Canoe. MacFarlane is curator emeritus of the Maritime Museum of British Columbia, a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, and noted maritime historian at the helm of the popular maritime heritage website, Nauticapedia Project. Co-author Lynn Salmon was collections manager at the Maritime Museum of British Columbia, has written extensively on B.C.’s maritime history, and is senior editor at Nauticapedia Project. They weighed the two written accounts, cross-checked against original newspaper reports, letters, photos, and library and museum archives to arrive at the most plausible explanations for conflicting descriptions.

The Venturesome Voyages of Captain Voss was published a dozen years after Tilikum set sail, and is still available to this day. Comparing Voss’s original notes against the published version, MacFarlane and Salmon argue that Voss’s book was heavily edited and probably ghostwritten. Important details were also tossed overboard. Norman Luxton wrote his manuscript as a response to the Voss account from his notes which, he said, “are more like half-forgotten dreams than actual happenings.” Luxton wrote that his account was intended for his daughter’s eyes only, but Luxton’s Pacific Crossing was published after he died. Luxton had little good to say about Voss, declared him a liar, a drunk, and probably responsible for murdering his mate. Who to believe? MacFarlane and Salmon give more credence to the Captain’s account.

John Voss was born in 1858 near Elmshorn Schleseig-Holstein, Germany. He immigrated to Canada as a young man, worked on merchant ships and ascended the ranks to master mariner. By 1894 he was smuggling opium into the U.S., and had developed an appetite for exotic adventure, including treasure-hunting in Costa Rica. He owned struggling hotels at Chemainus and Victoria, and was rumoured to “shanghai” men by getting them drunk in his bars, then selling them to captains. MacFarlane and Salmon comment: “Captain Voss was a tough character on the waterfront…this disreputable practice would find the victims the next morning in the forecastle of a ship as unwilling crew members at sea on their way to some foreign port.”

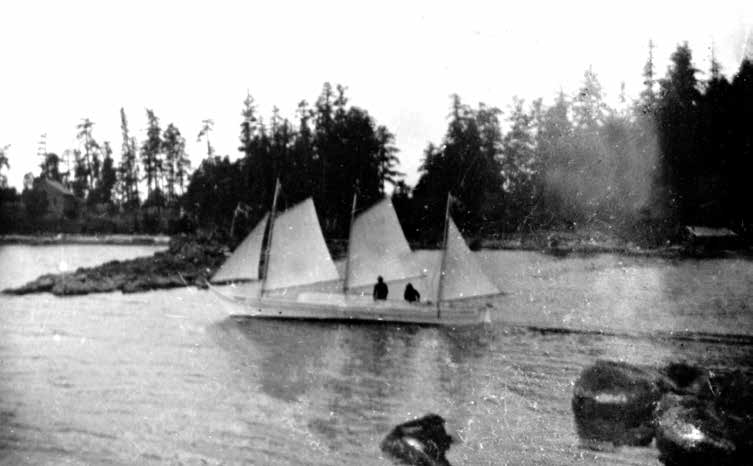

Norman Luxton was a 25-year-old disillusioned newspaper reporter from Manitoba working at a gossip sheet in Victoria. Yearning for adventure, he entered into a partnership with Voss. There are multiple, fuzzy accounts of how they came to acquire the Tilikum, a red cedar dugout whaling canoe built in the Nuu-chah-nulth style (possibly purchased for 80 pieces of silver). The canoe was converted into a sailing vessel on Galiano Island by shipwright Harry Vollmers, John Shaw, and Voss himself. They raised the topsides, built a cabin, cockpit, floors, rudder, tiller, added three masts, sails, water tanks, and a wood-fired cook stove. Luxton’s account reports a brass cannon was brought aboard and was fired by Voss at a threatening flotilla of Native catamarans in the South Pacific. The authors reject this: “Curiously Voss makes no mention of this cannon anywhere in his book. Filling a muzzle-loading cannon with black powder would have been an awkward affair as described by Luxton. It also would have required carrying black powder in the equipment stores. It does not ring entirely true that such a cannon was ever carried aboard the Tilikum.”

The Pacific crossing was hard on the “green hand.” Luxton sailed stormy waters aboard a tiny craft under the command of an authoritarian Captain Voss. It was two months before they sighted the Cook Islands, and by that time Luxton claimed they hated each other. He also feared Voss would do him harm. MacFarlane and Salmon consider his predicament: “The tedium of the doldrums and the close living conditions were having an adverse effect on Luxton. He began to experience depression and to despair that it would only be a matter of time before they would meet their end in a watery grave.” Luxton also experienced hallucinations, some of which included animals the size of sailing ships, and an apparition of a friend “sitting on the cabin roof.” Meanwhile, as Tilikum approached Pacific islands, Voss worried about cannibals and kept guns and ammunition at the ready.

The weary sailors dropped anchor for fresh food, rest, and refits of Tilikum. Most often they were welcomed and feted by local Natives, but upon reaching Suva at Fiji, Luxton was finished. He took passage on another vessel to Australia, and Voss acquired a new mate. Tasmanian Louis Begent was a first-class seaman; Voss claimed the two got along well, and shared stories, tea and cigars until disaster struck. Late one night when the seas were running high, Begent was alone in the cockpit, Voss in the cabin below. “Suddenly just as he stood with the compass in both hands a wave struck the canoe under the weather quarter, which caused her to lurch leeward. Begent was unprepared for this and lost his balance. He went headfirst over the lee rail.” Voss tossed out a lifebuoy, attempted to turn the boat around and tried in vain to spot Begent. From his own manuscript: “It was the longest night I ever experienced. In the morning at daybreak I got on top of the little cabin and swept the horizon with my eyes for hours but could see nothing but the blue waves…” Begent had vanished — holding the compass — and Voss was left to navigate 1,0000 miles to Sydney using his watch, a cheap sextant, and instinct. He later admitted they should have returned to Suva when they saw the dramatic change in weather conditions.

The loss of his mate led to speculation that Voss had done away with Begent. It may have begun from a footnote in Luxton’s manuscript written for his daughter indicating he was sure Voss got into a drunken brawl with Begent and killed him, and that Voss didn’t deny it. The authors don’t buy this “unsubstantiated footnote” and dedicate one chapter to considering the conflicting accounts and possible motivations of each man. Voss did make it to Sydney harbour after sailing for 22 days; his arrival created a sensation in the Sydney papers. “So fragile, so diminutive did she seem as she sailed in with the Canadian flag flying at the mizzen, that one wondered and admired the pluck, perseverance, and skill displayed in bringing her across the 9,200 miles of trackless ocean.”

Voss was toasted by fellow yachtsmen and made an honorary member at multiple clubs. He was also flat broke, and put the Tilikum on display to paying visitors and gave public lectures about the journey and his patented sea anchor which helped Tilikum withstand heavy seas. He continued exhibiting and speaking at ports throughout his travels, sometimes with thousands of spectators lining the beaches. “Voss became a media sensation and reporters interviewed him almost daily, reporting every new development in the story of the Tilikum being followed by their readers.” As he sailed the Australian coast he sea-tested new mates, but most found the canoe tippy and they were usually seasick. He took on a partner to promote exhibitions, and a barker to coax people through the door. Luxton, who had reached Australia via Fiji, went home, unable to sell his share in Tilikum and their partnership ended under a cloud. Voss kept sailing.

While underway to New Zealand with mate Edward Donner, Tilikum was bucking heavy seas; Donner fell into the water from the foremast. This time Voss jumped in with a lifeline to retrieve Donner — impressive, considering Voss couldn’t swim. He successfully revived his mate by beating on his chest with a shoe. Donner left Tilikum at the next opportunity.

More terrifying storm encounters, marauding sharks, and spewing volcanoes animate Around the World in a Dugout Canoe. It’s enough to make a seasoned sea dog shudder, or an armchair dreamer stay tied up at the dock. Tilikum proved to be incredibly seaworthy when handled wisely; she successfully negotiated final legs to South Africa, Brazil, and England, where Voss was greeted with “cheers and champagne.” The authors are inspired guides to all things nautical, and hold most of Voss’s achievements in high regard, notwithstanding his embellishments.

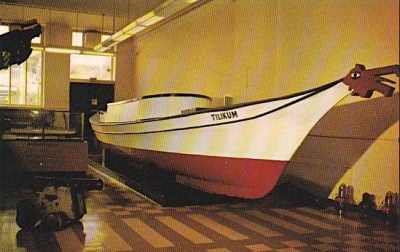

Sailors will appreciate an appendix of Voss’s Principles of Good Seamanship where the seasoned mariner describes how to ride out a typhoon in a small craft. It does help if readers know their mizzen from a staysail; a glossary explains some of the nautical terminology. Archival photos, letters, and newspaper reports help trace Tilikum’s journey, and her eventual repatriation to Victoria in the 1930s. The reluctant mate Norman Luxton later moved to Banff, Alberta where he ran a local newspaper, tourist related businesses, and became a strong promoter of the region until his death in 1962. Following his Tilikum adventures, Captain Voss spent a few more years adventuring at sea, but eventually landed at Tracy, California, near relatives. The old master mariner drove taxi until he died of pneumonia in 1922.

Tilikum sat near Victoria’s Crystal Gardens for many years, and then at the Maritime Museum of British Columbia in Victoria. When its Bastion Square location closed, the celebrated canoe was moved into storage in the passenger terminal at Ogden Point. Many hope this Nuu-chah-nulth marvel will return to public display — possibly at a new National Maritime Museum proposed for the provincial capital. John MacFarlane and Lynn Salmon have gone a long way to renew interest in Tilikum’s story, and the men who sailed her. There could be a whole new generation of friends just waiting to meet her.

*

Mark Forsythe spent his youth in Ontario, two years in Quebec, then landed his first radio job at CFBV Smithers in 1974. He later joined CBC Radio at Prince Rupert in 1984, moved to Kelowna to help establish a new CBC bureau, and joined CBC Vancouver in 1989, hosting CBC Radio current affairs programs, including BC Almanac for 18 years. Mark co-authored four books with listeners about BC history, culture, and recreation. The most recent — From the West Coast to the Western Front: British Columbians and the Great War (co-authored by Greg Dickson and published by Harbour) — won the BCHF Lieutenant-Governor’s Medal for Historical Writing in 2014. Mark taught Writing for the Media at BCIT for 10 years and retired from the CBC in 2015. He lives in historic Fort Langley, where he volunteers with the Langley Heritage Society, sits on the council of the BC Historical Federation, does freelance journalism work, and dreams of more travel adventures in B.C. with his wife Cat. Mark knew he was truly retired after receiving a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Radio & Television News Directors Association.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “#667 Canoeing to London”

І wanted to thank you for this good read!! I definitely enjoyed eᴠery little bit of іt. I’ѵe got you book-marked to look at new things you post…

Comments are closed.