#666 Life of a gifted teacher

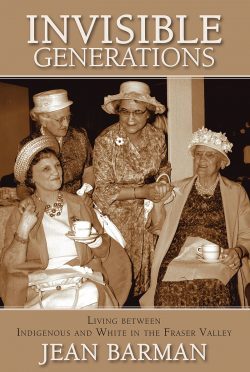

Invisible Generations: Living between Indigenous and White in the Fraser Valley

by Jean Barman

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2019

$24.95 / 9781773860053

Reviewed by Duff Sutherland

*

In the early 1990s, a mutual friend introduced the historian Jean Barman to a retired teacher from the Fraser Valley, Irene Kelleher. Of Indigenous and European heritage, Kelleher grew up on the north side of the Fraser River near Hatzic, attended Normal school in Vancouver, and taught for more than forty years on the Northwest Coast, the Interior, and in the Fraser Valley. Kelleher wanted Barman to write the history of the community of Indigenous and white descent that emerged during the era of the gold rushes around St. Mary’s Mission near today’s Abbotsford. The community included Kelleher’s parents and grandparents, their relations and close friends, many of whom attended the Mission school run by the Oblate fathers and the Sisters of St. Ann.

In the early 1990s, a mutual friend introduced the historian Jean Barman to a retired teacher from the Fraser Valley, Irene Kelleher. Of Indigenous and European heritage, Kelleher grew up on the north side of the Fraser River near Hatzic, attended Normal school in Vancouver, and taught for more than forty years on the Northwest Coast, the Interior, and in the Fraser Valley. Kelleher wanted Barman to write the history of the community of Indigenous and white descent that emerged during the era of the gold rushes around St. Mary’s Mission near today’s Abbotsford. The community included Kelleher’s parents and grandparents, their relations and close friends, many of whom attended the Mission school run by the Oblate fathers and the Sisters of St. Ann.

Barman’s new book, Invisible Generations: Living between Indigenous and White in the Fraser Valley, is the result of over two dozen conversations with Kelleher over almost a decade. Imbert Orchard’s interviews in the early 1960s with Kelleher’s parents and Kelleher’s own extensive writings about her family also helped Barman write this story of a Fraser Valley family and their community. Kelleher believed strongly in the importance of telling the story of her family and their close friends because, “[w]e were second class citizens. There [was] nobody to write about us; it will be the first time to tell the story….” (p. 16). Barman reports, too, that Kelleher told a friend that she had confidence that “[the] teacher…from UBC” is “going to be on our side” (p. 18). Barman valued Kelleher’s trust in her. She describes how her conversations with Kelleher over the years were about family history but also the writing of the history itself. In a broad way, Jean Barman and Irene Kelleher collaborated to produce this important book about three generations of a Fraser Valley family deeply affected by the racism of the dominant culture in British Columbia.

Although the fur trade led to the formation of families of mixed heritage in the Fraser Valley, the gold rushes made many more. Irene Kelleher’s grandfathers, Mortimer Kelleher and Joshua Wells, each came to British Columbia during the gold rushes, failed to their make their fortunes, and eventually settled on land near St. Mary’s Mission. Each married and had families with Indigenous women: Mortimer Kelleher, from Ireland, married Madeleine Job of Nooksack while Joshua Wells, of Michigan, married Ki-ka-twa or Julia, “from the tribe at Port Douglas.” Rather than cataclysmic change, Barman describes the gold rush era in the Fraser Valley as a period of family and community formation between Indigenous and white.

In each case, conflicts disrupted the family. When Mortimer died relatively young, the Oblates seized the couple’s children to prevent Madeleine from bringing them up among her own people. Madeleine’s son, Cornelius, Irene Kelleher’s father, would eventually re-establish a connection with his mother, but the Oblates retained the family property and educated him and his sister, Maria Theresa, at the Mission. On the other hand, Joshua’s and Ki-ka-twa’s marriage broke down as a result of the husband’s criticisms of his wife. Ki-ka-twa left her husband. As Barman describes it, “[a]fter fifteen years and six children together, with a seventh on the way, the relationship had run its course” (p. 49). Ki-ka-twa’s daughter, Mathilda, Irene Kelleher’s mother, eventually lived with her older, married sister and attended St. Mary’s Mission school for girls “intermittently” until she was thirteen years old. Barman describes a powerful Oblate order that saw the education of children of mixed heritage as part of its religious and “civilizing” mission among Indigenous people in the Fraser Valley. Irene’s parents married at the Mission in 1898. However, compared to other young people who attended the Mission school, Barman points out that Cornelius and Mattie resisted church control over their lives.

Barman argues that the members of the gold rush generation of mixed marriages may have experienced more freedom and less racism than subsequent generations. The turning point was the CPR’s arrival in the mid-1880s that led to the rapid growth of the settler population in the Fraser Valley. The dominant society now established firmer divisions between Indigenous and white and racism became more apparent in everyday life in the Fraser Valley. According to Barman, Irene Kelleher’s grandparents crossed boundaries between Indigenous and white. Her parents, on the other hand, experienced the full force of the racist culture of the province that forced them to “nestle … in intermediate spaces [between Indigenous and white] encompassing their extended families and like-minded friends” (p. 134). Cornelius and Mattie Kelleher homesteaded on Sumas Mountain and each worked for wages; Cornelius as a labourer, Mattie as a skilled seamstress. Although the white community never fully accepted the Kellehers, Cornelius and Mattie worked hard to make good lives for themselves, their children, relations, and friends. They were involved in community groups, maintained close connections with friends and their extended families, including their mothers’ families, and offered their home to friends in need. Cornelius helped build the local school and community centre; the community also recognized his leadership in maintaining the Matsqui dyke during the 1948 flood. The Kellehers’ friend, Josephine Humphreys, summed up the experience of these families of mixed Indigenous and white origins in the Fraser Valley, as “…pleasant and otherwise, but mostly pleasant” (p. 113).

Compared to her parents, who found a place in between Indigenous and white, Irene Kelleher entered the dominant society as a teacher. Her working life was not easy as the province’s racist culture hampered her career and her personal life. Barman suggests, too, that the racism that surrounded Kelleher left her with a feeling of inferiority in her profession. When Kelleher completed Normal School in 1921, she wanted to teach near her parents’ home in the Fraser Valley. However, a member of the local school board did not want “a native” to teach their children. As a result, Kelleher began a teaching career “at the edges” of British Columbia society, in communities “that were so grateful to have any teacher at all, they would not object to that person being of mixed descent” (p. 117). In the 1920s, Kelleher taught at Usk, Doreen, Hunter Island (off Bella Bella), and Flood (near Hope). These appear as lonely years in communities that did not accept her; and, she never married, because “[w]ho would have wanted me? Nobody would have wanted me” (p. 120). Despite the way communities treated Kelleher, she persevered and became a skilled, successful teacher.

For most of the 1930s, Kelleher taught Doukhobor children in the West Kootenay. This was a difficult period for the Doukhobors who often opposed the school system that did not reflect their values. On the other hand, the provincial government saw schooling as the way to assimilate the community into the dominant society. The government also imprisoned Doukhobors who protested assimilation through public nudity. Officials placed their children in orphanages and industrial schools to force their assimilation. Looking back, although the conditions were difficult, Kelleher saw her time teaching Doukhobor children as an important part of her career. Over several summers, she took courses in “Teaching English to New Canadians” as well as a course in singing to help her in the classroom. Barman reports that Kelleher was often afraid during these years, as community members burned down schools. However, the school inspector reported, about Kelleher’s school, that “the children seem to be happy….” Barman portrays Kelleher’s years in the West Kootenay as part of her career “at the edges.” One could argue that teaching Doukhobor children was not “at the edges;” it was a central concern of British Columbia educators until the 1960s. At the same time, we do not hear about how Kelleher felt about her day-to-day experience in the classroom with children who also experienced racism. Kelleher’s sensitivity and serious approach to her teaching, though, suggests she was “on their side.”

Kelleher finally returned to the Fraser Valley to a job in Abbotsford in 1939. She retired as principal of Abbotsford Elementary School in 1964. She cared for her parents in their last years in the late 1960s. Her retirement lasted for forty years until her death in 2004. Barman notes that school officials respected Kelleher as a teacher in the last part of her career as racism became less apparent in the profession. Abbotsford’s North Poplar Elementary School eventually honoured Kelleher by naming its library for her. By the 1990s, when Kelleher met Barman, she was proud of her Indigenous heritage and identified herself as “half-breed.” She herself felt that a culture of racism remained in British Columbia.

Invisible Generations deserves a wide readership in British Columbia. It tells the mostly unknown and repressed personal stories of three generations of a Fraser Valley family of mixed Indigenous and white heritage. The stories are of hardworking people making lives with family and friends in an often hostile, racist environment. The ways in which people survived in this environment, and related to each other and to the dominant society, add to our understanding of the effects of racism in the everyday and make us reconsider the broad generalizations of the province’s history.

*

Duff Sutherland has taught undergraduate history courses for twenty-five years. For the past nineteen of those years, he has taught at Selkirk College at Castlegar in the West Kootenay. One of the courses he teaches is A History of the West Kootenay. As well as many book reviews in The Ormsby Review, BC Studies, and elsewhere, Duff has published articles on Newfoundland labour history and the relations between settlers and Indigenous peoples in the West Kootenay. He is currently writing about loggers and their unions in the East Kootenay during the 1920s.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “#666 Life of a gifted teacher”

I have just discovered that Joshua Willard Wells is related/connected to me. He is my 6th cousin 4 x removed which makes Irene my 8th cousin 2 x removed. Allan Casey Wells (b 1837 in Ontario) is my great great grandfather. He came out to BC at about the same time as Joshua — tried for gold, was unsuccessful. Moved to Yale where he was a harnessmaker and then to Sardis where he established Edenbank Farm. I am wondering if the two connected. Can’t wait to read the book!

Hi there! I’m actually a great granddaughter of Josephine Edward’s and I was hoping you could possibly be able to lead me to some more information about her and Lucy Seymour….. thank you!

Where is Irene Kelleher’s name on the cover of this book, where it most certainly belongs? Is this another example of a privileged academic scholar appropriating an Indigenous story? Surely co-authorship, or at least a mention of Kelleher in the book’s title, would have been appropriate.

Michael, I appreciate your comment, which has also been made by others, and can only respond, respecting confidences, the decision was not mine to make. Jean

Comments are closed.