#647 Finding Anna Wong

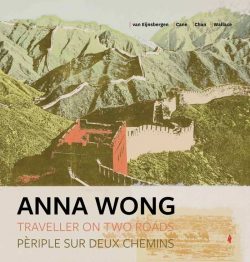

Anna Wong: Traveller on Two Roads

by Ellen van Eijnsbergen and Jennifer Cane (introduction) and Zoë Chan and Keith Wallace (essays), with a foreword by Maurice Wong

Burnaby: Burnaby Art Gallery, 2018

$40.00 / 9781927364314

Reviewed by Michael Kluckner

*

A handsome hardcover book published in 2018, five years after her death, has released printmaker and artist Anna Wong from ill-deserved obscurity. Born in Vancouver in 1930, Wong straddled Western and Asian cultures, both in her upbringing and her artistic output, while going her own way quietly with little acknowledgement from the Establishment arts community. The book’s publication coincided with an exhibition last autumn at the Burnaby Art Gallery.

A handsome hardcover book published in 2018, five years after her death, has released printmaker and artist Anna Wong from ill-deserved obscurity. Born in Vancouver in 1930, Wong straddled Western and Asian cultures, both in her upbringing and her artistic output, while going her own way quietly with little acknowledgement from the Establishment arts community. The book’s publication coincided with an exhibition last autumn at the Burnaby Art Gallery.

Anna Wong, Traveller on Two Roads (also entitled Périple Sur Deux Chemins — the book is presented with a French text running in the right-hand column of each page) is a publication of the Burnaby Art Gallery, apparently the only institution with a collection of her work, dating from her first success at a show there in 1965. The curators, Ellen van Eijnsbergen and Jennifer Cane, provide an introductory essay which is followed by two longer pieces, the first by Keith Wallace and the second by Zoë Chan, which cover some of the same ground in more detail. Wallace’s is the more contextual and accessible to the average reader, Chan’s the more analytical of Wong’s style and its meaning.

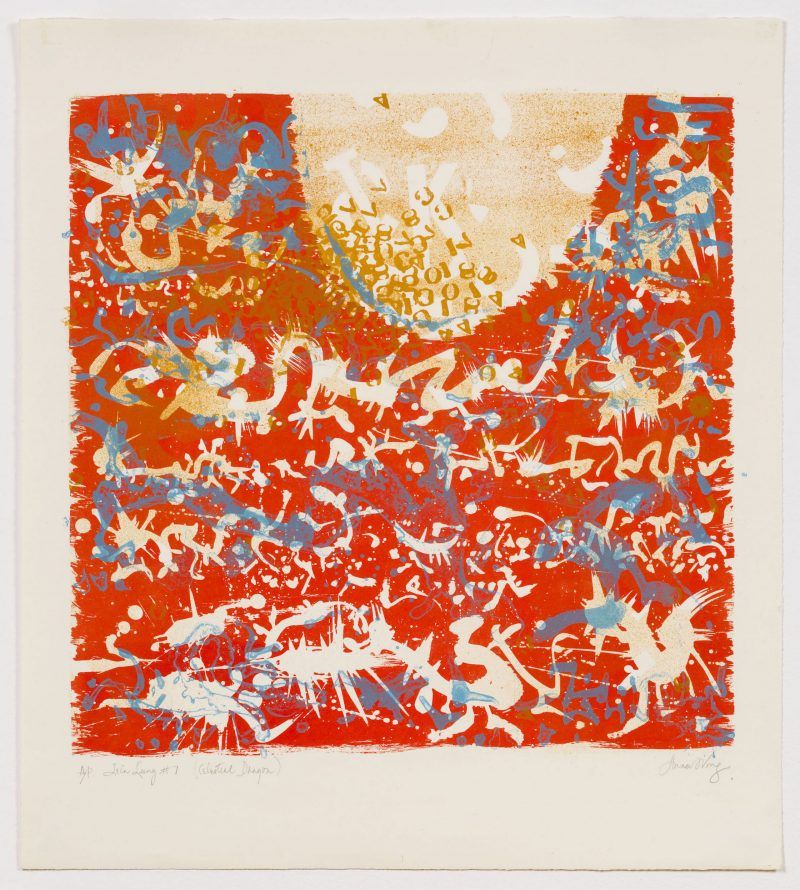

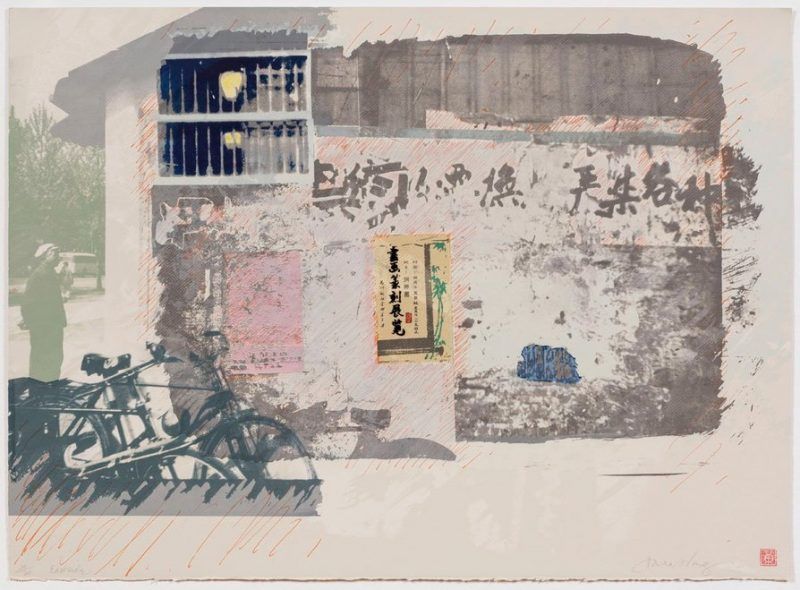

The balance of the book — about 70 pages — is a lyrical “gallery show” of Wong’s work, beginning with her traditional Chinese brush-ink pieces from the fifties, exploring the abstract drawings and prints from the sixties that brought her to the attention of the Burnaby Art Gallery, and concluding with the multi-media photo-based serigraphs (silkscreens) of the seventies and eighties that she produced in the later years of her career. The vast majority of them are “Collection of the Wong family,” with a few from BAG’s collection.

One theme is her role as an art teacher, initially of her own siblings when in her twenties. However, shortly after she moved in 1966 to New York City to study printmaking at the Pratt Graphics Centre, flush with scholarship money from her success in Burnaby, she was hired to teach it, and remained there until 1984. She also maintained a studio on Quadra Island, where she taught informally.

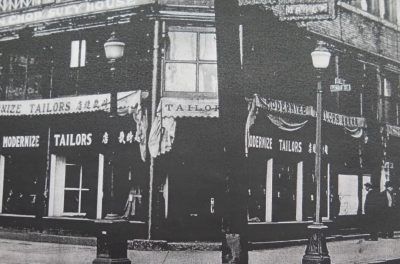

Her upbringing, as a daughter of the owners of Modernize Tailors, a prosperous institution in Vancouver’s Chinatown that designed clothes with a “modern, international perspective” (p. 30), influenced her profoundly. It gave her both the financial stability and a knowledge of fabrics that she came to incorporate into her later pieces, including large-scale quilts that were finished by Amish women in Pennsylvania. She worked briefly in the fifties as a bookkeeper in the family business, but was then able to travel to Hong Kong in 1957 to study traditional brush-and-ink painting with a master of traditional Chinese art. Decades later she made numerous trips to China, snapping photos of people, scenes, and objects that she incorporated into complex layered serigraphs reminiscent of Robert Rauschenberg’s.

Wallace writes of the influences of her teachers at the Vancouver School of Art in the early 1960s, including Roy Kiyooka and Ann Kipling, whose “lyrical abstract painting style … often referenced the landscape.” Wong’s emerging ink style was “suggestive … rather than literal,” a “multiplicity of mark-making” that “hover[s] between the representational and abstract” (pp. 28 and 31-2). The resulting works were abstract fields of fine lines, in some cases verging on a blizzard of implied shapes and tones, including her Morphallaxis XXIX that won an Honourable Mention in 1965 in the Burnaby National Print Show. As van Eijnsbergen and Cane note (p. 20), she was “always working with images in stark contrast with her surroundings” in “parallel journeys of the self”: the “Weeds” series of leaves and grasses, created in New York City’s concrete forest; layered Chinese images on sylvan Quadra Island.

As for her ethnicity and gender, Wallace notes that she chose not to fit into the identity politics of the 1970s. She adopted an “independent position” (p. 45) and stood apart from the commercial art scene, possibly neither needing the money nor craving the notoriety that might reflect poorly on her family. Wallace doesn’t speculate. Regardless, by the late seventies she reverted to forms from nature rather than pursuing any radical exploration of gender or culture, which perhaps explains why she found herself on the sidelines of the art world. The curators describe her as “virtually unknown to Vancouver’s arts community,” presumably meaning the one percent at the Vancouver Art Gallery and the few big commercial galleries in the city (p. 19).

Chan appears to have difficulty categorizing Wong in the art-historical spectrum. Focusing on her drawings of the 1960s, she links Wong’s stylistic development both to the Chinese intersection of drawing and calligraphy and to Western Abstract Expressionism. Drawing for Wong was, according to Chan, a practice “unrestricted by the requirement to be finished” (p. 65). Her later serigraphs, though, are very finished — finely considered layers of pale colours, complex surfaces, and usually a feeling of detached calm.

As I read the book, I found myself contrasting introverted Wong with her flamboyant contemporary Toni Onley (1926-2004), a painter who had some credibility as a modernist in the 1950s and who taught in the Fine Arts Department at UBC (where I learned the basics of serigraphy from him in 1972). He had moved in the sixties and seventies into a simplified landscape style, usually executed quickly and in vast numbers in watercolour. They became so popular that a “Toni Onley Day” and a “Toni Onley landscape,” usually of distant mountains and water, went into the local language. He further merchandised his output with editions of serigraphs that, if memory serves, were executed with the help of a Japanese craftsman in a studio in Gastown.[1]

Wallace (p. 39) gives a good, brief overview of this “limited edition print” craze of the 1980s, mentioning artists as diverse as Dali and Bill Reid. Locally, Onley’s style was effectively copied and mass-marketed by Markgraf, a German-Canadian trio whose affordable serigraphs of coastal scenes sold in the thousands. Painters like Robert Bateman were featured in national newspapers as they signed editions of several hundred copies that were reproductions from offset printing presses, supervised by chartered accountants who certified that the press was shut off at the required time and all excess copies were destroyed. This situation continues today with giclée (ink jet) reproductions sold as limited editions by artists who want to market copies of their best paintings.

These were not hand-pulled “craft” prints, like the serigraphs and lithographs produced by master printmakers such as Wong and her compatriots at the Malaspina Printmakers Society. Wong’s serigraph editions were small, many only 10 copies, lending a cachet to them in keeping with the idea of fine art. But did they sell? Did she have followers, fans, or collectors? Chan and Wallace don’t say.

The reader comes away from the book with a vague sense of melancholy — sadness that Wong didn’t have more public success and more private sales of her work (if indeed she didn’t — it isn’t clear), and curiosity about her personal life. Perhaps as a gesture of respect to the Wong family there is no speculation about her private life, her sexuality, or any of the other staples of 21st-century biography. For people more interested in artists than art — in the lifestyle of art-makers rather than their work — this book will be a disappointment.

However, Anna Wong’s art is quite able to stand on its own and give pleasure through this beautiful and interesting presentation. Like the diverse artists of Mona Fertig’s “Unheralded Artists” series, Anna Wong deserves a posthumous resurrection.

*

Michael Kluckner is an author-illustrator of books on heritage, landscape and farming, as well as three graphic novels. He came to know Toni Onley both as a student in the early seventies and as a fellow artist in the Centennial Fine Art poster series of 1986. His most recent art project, with New Zealand artist Maddie Leach, is called Lowering Simon Fraser and is recorded in a book published by the Contemporary Art Gallery in Vancouver.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] Onley’s float planes that he used for quick access to the wilderness scenes he wished to paint, and the Rolls Royce he purchased after a $930,000 sale in 1980 of 800 accumulated paintings to a businessman known only as the “Fraser Valley Phantom,” brought him in 1983 to the attention not only of the media but of Revenue Canada, which threatened to tax him on his unsold inventory, reckoning that his write-offs of airplanes and a luxury car made him more a manufacturer than an artist. Onley responded with a marvellous stunt – witnessed by national TV crews – when he threatened to destroy all his work in a bonfire on Wreck Beach, eventually leading to changes in Canada’s tax laws for self-employed artists and writers. Many years later, after a broken marriage and an attempt to return to a more introspective art style, he made a final big splash when he crashed his float plane into the Fraser River, killing himself.