#646 An abiding hunger for art

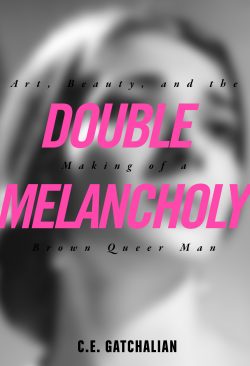

Double Melancholy: Art, Beauty, and the Making of a Brown Queer Man

by C.E. Gatchalian

Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2019

$18.95 / 9781551527536

Reviewed by Vincent Ternida

*

“I live for art.” This is how C.E. Gatchalian commences his brief but dense collection of interconnected personal essays in Double Melancholy: Art, Beauty, and the Making of a Brown Queer Man. The prologue clearly defines his thought process for the title: it is “the melancholy of being queer and the melancholy of being brown.” As the essays unfold, they tell the story of a second generation Filipinx-Canadian who struggles with navigating the in-between in his diverse high school set in Vancouver, his rise to glory as a talented playwright in the LGBTQ+ community, and even now, as he enters middle age, a continuing account of how art saves him in every aspect of his life.

“I live for art.” This is how C.E. Gatchalian commences his brief but dense collection of interconnected personal essays in Double Melancholy: Art, Beauty, and the Making of a Brown Queer Man. The prologue clearly defines his thought process for the title: it is “the melancholy of being queer and the melancholy of being brown.” As the essays unfold, they tell the story of a second generation Filipinx-Canadian who struggles with navigating the in-between in his diverse high school set in Vancouver, his rise to glory as a talented playwright in the LGBTQ+ community, and even now, as he enters middle age, a continuing account of how art saves him in every aspect of his life.

The essays unfold in three fragmented narrative voices: the Voice Proper, which serves as a reader’s guide to and curator of Gatchalian’s personal and artistic life; the Journals, which serve as a primary source of Gatchalian’s experience as a youth in turmoil — the voice of an angry youth yearning to break free from the cage created by a patriarchal society guided by white supremacy — and then his path as a burgeoning queer man negotiating his path of artistry; and the Voice of Decolonization, which serves as a potential self-critique that seems to answer, almost telepathically, the budding questions that readers might formulate as they read the early parts of the book.

Gatchalian thus converses with three versions of himself. These voices represent past, present, and future as they rotate between memoir, art critique, and a reflection of self. Connecting them all is a hunger for art. Gatchalian takes readers on a personal guided tour and gives them a front-row seat in his life story and his love affair with art. He lays himself bare, exposing his soul for the world to see. Double Melancholy is a 130-page art installation that manifests in the mind’s eye.

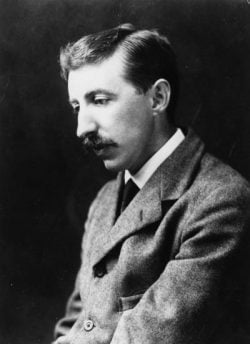

The first half of the book, detailed in four chapters, consists of coming-of-age, bildungsroman-style adventure pieces. In these essays, Gatchalian considers the work of four literary influences (L.M. Montgomery, E.M. Forster, Tennessee Williams, and Thomas Mann) and explains how their characters (Anne Shirley, Lucy Honeychurch, Blanche DuBois, and Gustav von Aschenbach) stand as milestones from his youth. From his early recognition for proficiency in piano, to his shaky relationship with his English teacher, to fear of the AIDS epidemic, and eventually to coming out, Gatchalian masterfully links how these art pieces, characters, and authors serve as ethereal messages in bottles discovered through the maelstrom of time and space.

The journal entries are a welcome mirror into his awkward and tumultuous youth. The emotions written in lyrical prose are raw, naked, and vulnerable. Gatchalian reveals to the readers his deep-seated desires, dreams, secrets, peeves – just about every aspect of his personality is on display. The decolonized voice takes swings and potshots at the nebbish and ignorant child with annoyance as it corrects the colonial socialization that Voice Proper and the Journals address. Yet, during my first reading, this approach suggested hubris and needlessly proselytizing. On my second read-through, the decolonized voice came through more clearly as an invitation to the audience to address their concerns, doubts, and fears.

The second half of Double Melancholy pulls no punches with regard to Gatchalian’s sexuality. His parallel to Queer As Folk (TV series, 2000-2005) provides a rapturous catharsis as we engage the moments that explore the hypersexuality of his adult life. It is as if all the setup in his youth comes to a rupture. The content is graphic but fitting in this discourse. Readers will root for him in his conquests as he plays catch-up to time lost in finding himself. While Gatchalian speaks so much of the major influences – Camille Paglia and Susan Sontag – of his maturity, and of their intellectual and cultural contributions to queer thought and literature, they are by no means granted carte blanche as he explores the limitations of their work. His idolization of Maria Callas reveals his own quest for artistic self-actualization. And yet he also addresses his colonial mentality in which, paradoxically, the influences in his art have been limited to largely white artists and thinkers.

For Gatchalian, his brownness plays second fiddle to his queerness. Writing as a third culture Filipinx immigrant, I anticipated hearing more about his Filipinx perspective. But I understand Gatchalian’s restraint because continually flogging the self-hating brown narrative would become exhausting, even if it were presented humbly and directly. He expresses his observations of other first generation Filipinx acquaintances, friends, and lovers and how they navigate this shaky ground of colonial mentality. At the end of the book he asks a lot of profound questions that are surely to be addressed in a separate work.

On my first reading, I felt that the voice of decolonization diluted the vulnerability of the two other voices. I can understand the need for political awareness, but to me the third section, Voice of Decolonization, stifled the impact of his vulnerability presented in earlier chapters. It seemed to threaten to diminish the journey instead of adding to it. I almost felt that readers were being deprived of critical thought and needed to be guided towards the “right way of thought.” At times I felt in the company of a magician annotating his tricks. Used sparingly, the Voice of Decolonization would’ve heightened the experience, but its length seemed to wear off the welcome.

That was my first reading. On my second, I understood and experienced why the decolonized voice exists: it provides an active conversation between Gatchalian and the reader. It invites the writer to a conversation rather remain a passive read-and-shelf book where the lessons learned will be forgotten.

The brevity of Double Melancholy adds to its versatility. One can read and reread it at different times to digest and continue the conversation about decolonization in one’s future readings. In a way, the book’s potential is akin to Gatchalian’s way of discovering messages in bottles from his artistic progenitors. Double Melancholy is his message in a bottle for People of Colour, whether they be Filipinx, Latinx, from the African diaspora, Indigenous, queer, or part of the heteronormative majority. One need not adhere to either of his specific melancholies to relate to Gatchalian’s plight. As a Filipinx-Canadian author, I can’t name many male Filipinx-Canadian works to peruse. Aside from Miguel Syjuco, only C.E. Gatchalian stands out as a household name. This book is a valuable resource for the diasporic narrative and Filipinx experience. As a cisgender man, I found that the memoir both engaged and permitted me to have a window to the queer story.

More Filipinx men, and men in general, of the heteronormative majority could learn a thing or two from Gatchalian’s perspective. He re-defines the male narrative to invite another side to be welcomed and explored. Double Melancholy is part of the deluge from an ongoing wave of stories from people of the Filipinx diaspora – of which the book is a welcome addition, and of which Gatchalian is a pioneer.

*

Vincent Ternida’s works have appeared in Ricepaper Magazine and Dark Helix Press, and his story “Elevator Lady” was long-listed for the CBC Short Story Prize in 2019. His first novella is The Seven Muses of Harry Salcedo (Ricepaper and Asian Canadian Writer’s Workshop, 2018), and he has a collection of short stories in development. He lives in Vancouver.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster