#644 The Canadian genocide

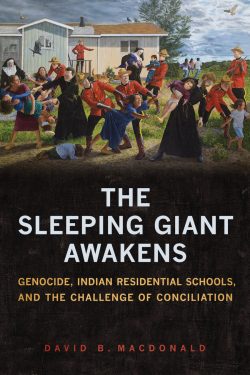

The Sleeping Giant Awakens: Genocide, Indian Residential Schools, and the Challenge of Conciliation

by David B. MacDonald

Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2019

$24.95 / 9781487522698

Reviewed by David Milward

*

When one hears the word “genocide,” it is easy to instantly think of the Holocaust and then not take it any further than that. As it turns out, that may be exactly what Western liberal democracies want with respect to their populations. David MacDonald’s excellent book, The Sleeping Giant: Genocide, Indian Residential Schools, and the Challenge of Conciliation, provides an in-depth exploration of how the term “genocide” has been contested terrain from its very inception, and remains so to the present day. The conception of the term “genocide” and its existence as a source of legal grievance owes its existence to a legal scholar named Raphael Lemkin. Lemkin personally experienced racial persecution as a Jew in his native Poland, worked as a labour lawyer for the working class, and barely escaped to Sweden before the Second World War invasion of Poland. It is not hard to see that his background motivated him to make legal recognition of genocide his life’s work.[1]

When one hears the word “genocide,” it is easy to instantly think of the Holocaust and then not take it any further than that. As it turns out, that may be exactly what Western liberal democracies want with respect to their populations. David MacDonald’s excellent book, The Sleeping Giant: Genocide, Indian Residential Schools, and the Challenge of Conciliation, provides an in-depth exploration of how the term “genocide” has been contested terrain from its very inception, and remains so to the present day. The conception of the term “genocide” and its existence as a source of legal grievance owes its existence to a legal scholar named Raphael Lemkin. Lemkin personally experienced racial persecution as a Jew in his native Poland, worked as a labour lawyer for the working class, and barely escaped to Sweden before the Second World War invasion of Poland. It is not hard to see that his background motivated him to make legal recognition of genocide his life’s work.[1]

The fruit of Lemkin’s tireless endeavours was the international recognition of genocide as a crime against humanity that could be condemned and sanctioned by the then infant United Nations. And yet even this achievement may have been bittersweet for Lemkin. Having witnessed atrocities not just during the Holocaust but also in the Armenian Genocide during the First World War, Lemkin initially wanted a very broad definition of genocide to provide the foundation for the new legal concept. His conception would have included not just mass murder as the most obvious example of genocide, but also other state-sponsored destructive efforts such as forcible transfers of populations, the forced taking of children from their families, and policies aimed at cultural destruction.

MacDonald documents how Western liberal democracies, once aware of Lemkin’s efforts, immediately saw the burgeoning concept of genocide not just as an opportunity to get with the times, so to speak, but also as a battleground where they needed to insulate themselves against foreseeable grievances. The final product was the definition of genocide found in Article II of the United Nations’ Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948):

In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

- Killing members of the group;

- Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

- Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

- Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

- Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.[2]

Note the exclusion of cultural genocide, which Lemkin regarded as a personal failure. Lemkin found himself on the unfortunate side of the eternal clash between idealism and pragmatic politics. The support of western liberal democracies was necessary to get the legal recognition of genocide off the ground. Those democracies had no issue with including the most obvious instances of genocide, as they were on the winning side of the Second World War against the Nazi regime in Germany. Other examples of genocide, the forced transfer of children and cultural genocide, were different matters because western states could anticipate grievances against them stemming from their colonization of Indigenous peoples. And so Lemkin found himself having to compromise his initial vision or risk losing any legal recognition of genocide that he had worked so hard to obtain. The forcible transfer of children was included, but even that was an instance where Lemkin had to fight hard against concerted opposition, and for similar reasons. Canada continued to shore up its position against claims of genocide when they defined its prosecutable genocide offence — under section 318 of the Canadian Criminal Code — as including only mass murder and inflicting fatal conditions on a group of people.

MacDonald proceeds to argue that numerous actions on the part of the Canadian state qualify as genocide, either under what is recognized in the Convention or according to Lemkin’s original vision. MacDonald considers the exercise important as it demonstrates that Canada’s ongoing denial of genocide against Indigenous peoples remains unacceptable. The historical record shows a condemning combination of horrific effects on Indigenous peoples (even those that did survive), and either deliberate policies or inhumane inaction in the face of awareness on the part of the state. It is not just finagling over the contours and parameters of legal definition. It is fundamentally a demand for humanitarian recognition and righting injustices.

For example, MacDonald holds out that it is important to hold Canada accountable for cultural genocide along with the well known physical and sexual abuse that took place in Residential Schools. In turn, this cultural genocide has had damaging repercussions far beyond the immediate survivors of the abuse, and contemporary Indigenous communities struggle with enduring social fallouts that can be blamed at least partially on the erosion and denigration of their cultures and value systems over generations.

As another example, MacDonald makes a solid case for Canada’s use of the forced removal of children and the prevention of Indigenous births as genocidal policies. Older provisions of the Indian Act made an Indigenous woman lose Indian status, including the right to reside on the reserve, if she married a non-Indigenous man. A non-Indigenous woman who married an Indigenous man gained full status, including the right to reside on reserve. Correspondence and public statements by state officials openly admitted that the policy objective was to breed out Indigenous peoples so that biological assimilation and disappearance would be completed in a matter of decades. The Sixties Scoop involved the mass use of the power to apprehend Indigenous children by social workers. We do not have an overt statement of policy like we do with the Indian Act provisions. And yet there is no mistaking that the Scoop involved a fundamentally racist misapplication of the best interests of the children legal test, and on such a scale that it cannot help but be condemned as a policy designed to destroy Indigenous peoples from within any society’s most fundamental units, their families.

In places MacDonald is willing not only to diverge from official Canadian positions, but also from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission itself. It is well known that numerous Indigenous people died of tuberculosis in both the reserves and the Residential schools. MacDonald documents an appalling combination of state awareness of the problem and refusal to take measures that could have ameliorated the crisis, such as improving living conditions and nutrition, which could have combated the spread of the disease. The Commission was careful to avoid outright condemnation on that particular issue, as there were questions about the strength of the evidence in favour of such a conclusion. MacDonald makes a case for condemning the whole tuberculosis crisis as containing conditions for the destruction of Indigenous peoples as a group.

MacDonald also explores ways forward, and there are two halves to his equation. One half is that it is crucial for Canada to accept responsibility for both the previous acts of genocide and their ongoing social legacies, which requires far more than a momentary verbal apology. It requires an ongoing acceptance of responsibility and a memorializing of what happened, so that future generations do not forget. The first half is integrally bound up with the second half, the requirement that Indigenous peoples gain self-determination so that they can address the enduring legacies in their own ways and with their own interests as priorities. For Canada to truly accept responsibility and make good with its past mistreatment of Indigenous peoples, and go beyond hollow apology, requires a considerable surrender of power and resources so that self-determination can become meaningful.

If I perceive any relative shortcomings in The Sleeping Giant Awakens, it is that the ways forward exploration could have been more extensively developed. I would have liked more concrete and detailed depictions of how MacDonald might see Indigenous determination playing out in the real world, and how Canada could begin to address the ongoing problems. But at the same time, I appreciate that MacDonald’s key objective was to make the strongest possible case that Canada committed genocide against Indigenous peoples through numerous actions and policies, and not just those directly associated with the Residential Schools. And in that respect he has definitely succeeded.

If I perceive any relative shortcomings in The Sleeping Giant Awakens, it is that the ways forward exploration could have been more extensively developed. I would have liked more concrete and detailed depictions of how MacDonald might see Indigenous determination playing out in the real world, and how Canada could begin to address the ongoing problems. But at the same time, I appreciate that MacDonald’s key objective was to make the strongest possible case that Canada committed genocide against Indigenous peoples through numerous actions and policies, and not just those directly associated with the Residential Schools. And in that respect he has definitely succeeded.

I realize that a lot of contemporary Canadians will never pick up this book for fear of having to confront some uncomfortable truths. I sincerely hope that The Sleeping Giant Awakens becomes well-known, even if by word of mouth, so that enough non-Indigenous Canadians can finally understand why these issues are not just a thing of the past but of ongoing importance.

*

David Milward is an Associate Professor of Law with the University of Victoria, and a member of the Beardy’s & Okemasis First Nation of Duck Lake, Saskatchewan. He assisted the Truth and Reconciliation Commission with the authoring of its final report on Indigenous justice issues, and is the author of Aboriginal Justice and the Charter: Realizing a Culturally Sensitive Interpretation of Legal Rights (UBC Press, 2013), which was joint winner of the K.D. Srivastava Prize for Excellence in Scholarly Publishing and was short-listed for Canadian Law & Society Association Book Prize, both for books published in 2013. David is also the author of numerous articles on Indigenous justice in leading national and international law journals.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] Raphael Lemkin, Axis rule in occupied Europe: laws of occupation, analysis of government, proposals for redress (Clark, New Jersey: Lawbook Exchange, 2008).

[2] UN General Assembly, Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, 9 December 1948, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 78, p. 277.

Comments are closed.