#639 The characters of English Bay

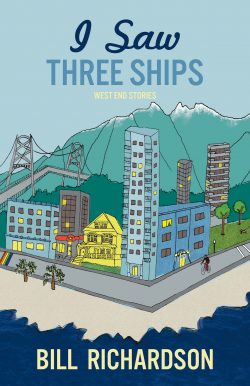

I Saw Three Ships: West End Stories

by Bill Richardson

Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2019

$16.95 / 9781772012330

Reviewed by Harvey De Roo

*

In his introduction to this delightful book, Bill Richardson assures us in a Wildean mot that “The past is far too precious to waste on something as cheap as nostalgia.” But I Saw Three Ships is suffused with nostalgia. Why else set all the stories at Christmas time — though not the Christmas of the carol, no turkey and trimmings, a cheery fire, the family gathered at the groaning board, but of a man who can’t go home to his empty condo because of his skunk-drenched dog, ruing his losses, or a woman forced to move owing to development, sorting through a lifetime, or the two dumpster divers collecting the detritus of her past, or a man walking home through the snow in a wedding dress stored at his facility, or a gay man attending midnight mass with his fading mother.

In his introduction to this delightful book, Bill Richardson assures us in a Wildean mot that “The past is far too precious to waste on something as cheap as nostalgia.” But I Saw Three Ships is suffused with nostalgia. Why else set all the stories at Christmas time — though not the Christmas of the carol, no turkey and trimmings, a cheery fire, the family gathered at the groaning board, but of a man who can’t go home to his empty condo because of his skunk-drenched dog, ruing his losses, or a woman forced to move owing to development, sorting through a lifetime, or the two dumpster divers collecting the detritus of her past, or a man walking home through the snow in a wedding dress stored at his facility, or a gay man attending midnight mass with his fading mother.

The author may try to disguise his nostalgia with wit and a bag of narrative tricks, but the inescapable mood of the book is elegiac. It’s about many kinds of loss — of spouses and lovers, of a chance at love, of a mind to Alzheimer’s, of affordable housing, of community, of a generation of young men, of a way of life. Most of all, of mothers. But, like its author, the book is plucky. And maybe its ironic mode of presentation is not so much an attempt at disguise as at self-protection, for there is in the book a deep affection for its characters and a recognition that the shrugs and wry smiles elicited by the incongruities of life mask an underlay of sorrow.

The stories in I Saw Three Ships are character driven. And where do you find more characters than in the West End of Vancouver? Gays and straights, old folks, young folks, drag queens, yuppies. Not long ago, a population of sex trade workers, of flamboyant gay life, and of plagues – “development” and AIDS. Even here, nostalgia plays its role. The glory days and seismic traumas of the West End may have passed but echoes linger. And, while its characters’ lives may be less flagrant than their predecessors’, they are hardly those of suburban dwellers. The neighbourhood remains one of unconventionality, vibrancy, and change — and a good share of heartache.

The West End as Richardson chronicles it is a mosaic, and this is an apt description of the style he chooses. First of all, the stories are linked, with characters reappearing in other stories, and so in that way forming a montage. Each story is also told in pieces — like tiles forming a larger picture of the community. Constant segues from one character to another or one narrative to another, one time to another, either in larger chunks or in brief flashes. Sometimes you’re not quite sure why a tile is there. The obliqueness keeps you on your toes, but the reward is a larger, accruing history — though never the full story. There is no full story, only the unknowables that make up life here on this planet and make it so baffling, so compelling.

The first story makes a perfect start. “I Saw Three Ships” centres on the occupants, past and present, of an apartment building called the Santa Maria — slated along with two neighbouring walkups for transformation into a development to be called “Three Ships.” What better way to introduce a set of West End stories than with such a microcosm? Here is Rosellen, the building manager who bolted from a bad marriage many years ago, who looks after the building and its many occupants, in a myriad of ways; or Bridget, a cranky old-timer who wants things done the proven way but is not so hard to win over; or Bonnie, a long-time resident, a free-lance photographer, just successful enough to scrape by; Philip, a gay man and Bonnie’s best friend, who doesn’t live in the building but horns in on its communal life; their running gag of pet names, Davie Denman and Nicola Harwood; their fascinating complex of emotions over Philip’s romantic involvement with Gary; Vidal, the exhibitionist living in the building opposite, providing Bonnie over the years with a special show once a week; J.C, a former manager of the building, who killed himself when he discovered he had AIDS, and who has become a benign ghost, playing with Rosellen every Christmas a game of Hide-the-Christmas-Tree-Angel. And on it goes. Many stories, many lives. And always the passage of time, loss, and the determination to face it out.

The second story, “Everybody knows a Turkey,” uses the narrative device of a man locked out of his condo with his skunk-sprayed dog, a perfect emblem of his outsider status, of his loss of wife and brother (J.C.). And how piquant that the man now taking his place with his ex should also be called Conrad. Though perhaps less so than Conrad’s naming his three-legged dog after his wife Minnie.

“Snow on Snow on Snow” tells of the mystery of Leonard Cohen, inheritor of his father’s storage facility for wedding dresses, now walking home through the snow in one of his charges. Adding to the quirkiness of this story is its telling from the point of view of Saint Ziti of Lucca, who has been sent to help Leonard get safely home. And of her securing a heavenly choir — the Halleluiah Holler (imagine!) — to sing Leonard Cohen songs to ease the way. These narrative oddities and the presentation of the politics of heaven, having gone high-tech thanks to its alliance with hell, and the fact that everyone in the story is named after a celebrity, lend the story a magic realist quality. Perhaps a little tacked on — some gags for their own sake — but a hoot.

And on it goes with its poignant stories and narrative tricks — the letter to Peter Gzowski; or the phantom editor, Lydia de’ath. About the middle of the book things turn darker: Bonnie’s letter expressing loss of her mother Gloria; the disturbing story of how Gloria lost her job and professional self; Philip’s mother gamely dying of cancer; Gary choosing his ailing mother over his lover. All of them carried by Richardson’s distinctive voice, his ear for the language, his gift for the arch observation, the pungent turn of phrase.

The last story, “Sin Error Pining,” is a gem, with its movement back and forth in time and place, its tender narrative of love between son and mother, mutual devotion not entirely overlapping in time — the mother’s for her little boy and young son, the middle-aged son’s for his mother struggling with dementia, and the years between with her weekly phone calls to Vancouver, the toxic insults from her grown son’s “roommate” she is willing to wait out. Which she does: Gary finds Philip cruel about her one time too many and leaves him. When he gets news of her condition, he returns to her, half way across the country. Layered into this, Gary’s childhood recognition of his difference, the importance of midnight mass and the annual rendition of “O Holy Night” by a tenor who has been a choir member forever, a life-long bachelor and lonely innocent. All with a humane perception of fallibility and vulnerability. Perhaps the most touching moment in the story — indeed the whole book — shows us Gary—repressed and having been no match for the acerbic Philip — weeping gratefully in the arms of his husky, tattooed new lover, who has just called him “Gare Bear.” A compassionate book, then, with the added bonus of being quirky, at times waggish, but never condescending.

*

Harvey De Roo was a professor of Old, Middle, and Early Modern English language and literature and Old Norse language and literature in the English Department at Simon Fraser University. In the eighties he was Editor of West Coast Review. Upon retirement, he taught opera history and appreciation in the SFU seniors programme at Harbour Centre. He was founding secretary of City Opera Vancouver and served on the board and Artistic Planning Committee for several years. He was the opera reviewer for Vancouver Classical Music (vanclassicalmusic.com) from 2014 to 2018 and lectures annually to the Vancouver Opera Club. A former resident of Vancouver’s West End, he now lives on Salt Spring Island.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Comments are closed.