#498 Poems of faith and simplicity

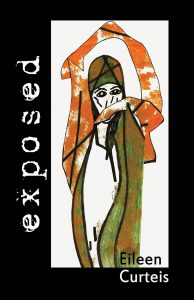

Exposed

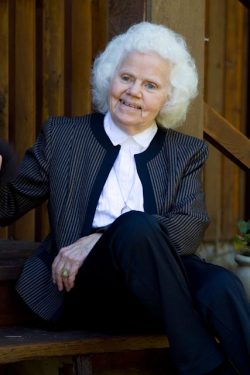

by Eileen Curteis

Terrace: CCB Publishing, 2018

$44.06 (via Amazon) / 9781771433594

Reviewed by Phyllis Reeve

*

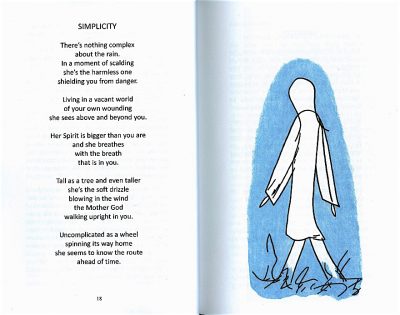

A poem named “Simplicity” begins: “There’s nothing complex/ about the rain.” I ponder the significance of that statement, which seems to me debatable. Then a personality named Simplicity enters the poem to tell us the “soft drizzle” is “the Mother God/ walking upright in you,” and I am thinking this might not be so simple after all. But the poem insists on “simplicity” right up to its conclusion: “Uncomplicated as a wheel / spinning its way home/ she seems to know the route ahead of time.” I remember how the words of T.S. Eliot in “Little Gidding” — “a condition of complete simplicity (Costing not less than everything)” — lead us to the fourteenth-century mystic Julian of Norwich.

A poem named “Simplicity” begins: “There’s nothing complex/ about the rain.” I ponder the significance of that statement, which seems to me debatable. Then a personality named Simplicity enters the poem to tell us the “soft drizzle” is “the Mother God/ walking upright in you,” and I am thinking this might not be so simple after all. But the poem insists on “simplicity” right up to its conclusion: “Uncomplicated as a wheel / spinning its way home/ she seems to know the route ahead of time.” I remember how the words of T.S. Eliot in “Little Gidding” — “a condition of complete simplicity (Costing not less than everything)” — lead us to the fourteenth-century mystic Julian of Norwich.

Sister Eileen is a mystic, a 21st century mystic, and a local one, born and raised in Victoria (Curteis Point in North Saanich is named after an ancestor). In 1961, aged nineteen, she entered religious life as a member of the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Ann. In the introduction to this book, she recalls, “Nobody had told me about mysticism, but when I encountered it I knew I would be in love with Love forever. Fifty-seven years later it is no different. The mystical truth inside the human journey is what spurs me on to be a co-creator with God whether it be in my teaching, healing work or the literary arts.”

The theologian Paul Tillich tried to define mysticism as as “an experience of the presence of the infinite in the finite,” and that seems right. The mystic does not reject the finite human journey, but may instead enter it more deeply than most of us do.

The theologian Paul Tillich tried to define mysticism as as “an experience of the presence of the infinite in the finite,” and that seems right. The mystic does not reject the finite human journey, but may instead enter it more deeply than most of us do.

Certainly not a recluse, Eileen has been a classroom teacher and principal. Later, she became a practitioner and instructor in the healing ministry of Reiki. She is a poet and artist, a producer of CDs and films and author of prose books, often related to Reiki but including one biography, Witness For Our Time, the story of Blessed Marie Anne Blondin, foundress of the Sisters of St. Ann.

Her art too is “somewhat of a mystery” but the “Love Force” that she feels guiding her hand has not impeded the development of a signature style, the mark of an authentic artist.

I first saw her drawings in Moving On: Poems and Sketches (Ekstasis Editions, 1997). These, like the cover image on her recent CD Lighthouse Shining in the Sea: Healing Poems and Songs, she rendered in what she describes as “stark” black and white; but their emotional impact, with that of the matching poems, is anything but “stark.”

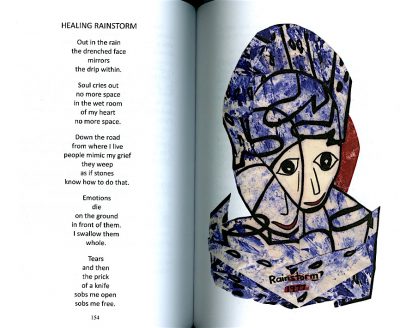

The watercolours and pastels in this new book came first — long before the black/white drawings, but only now “exposed” to publication: 58 original works of art created over forty years ago. I would say the wash gives them a jewel-like quality, but they are softer than most jewels. The figures are often hooded, their eyes not yet wide open as in the later drawings; they are waiting to see and to be seen, to be exposed. The poems and prose that accompany each painting are new and intended to reveal the continuing journey of her soul.

The watercolours and pastels in this new book came first — long before the black/white drawings, but only now “exposed” to publication: 58 original works of art created over forty years ago. I would say the wash gives them a jewel-like quality, but they are softer than most jewels. The figures are often hooded, their eyes not yet wide open as in the later drawings; they are waiting to see and to be seen, to be exposed. The poems and prose that accompany each painting are new and intended to reveal the continuing journey of her soul.

Sister Eileen was defining her artistic identity during the 1970s, the era of Women’s Lib and New Age experiments. Considering the tender age at which she acknowledged her religious vocation, most elements of the New Age must have seemed to her pretty Old. Yet both Aquarius and Feminism offered unexpected insights into ancient situations. As St. Ann’s archivist Carey Pallister notes in her Preface, “Coming from a hierarchical ethos, where she struggled and often felt her diminishment, Eileen has now reclaimed her individuality and found her voice immersed within, while at the same time, being very present to the Religious Community she loves.”

Eileen often but not always uses a feminine pronoun to refer to God. “Even before her arrival/ we know her Voice/ will be the greening of us” (Beloved Messenger). In “Woman Alive” she writes “Putting all this aside,/ sometimes/ a woman’s emergence / is like that. / You say to the demon in you, / ‘Up now/ and live/ and you do live!'”

Pallister’s word “diminishment” is perceptive. The person in these poems is small, diminutive, and waiting to attain full stature at a stage when her “wings / are too wide/ to become small/ again” (Spiritual Rebirth). “A tiny morsel of light” is “so large. you can hardly see” (“Humility”). She has strange names, Fly, Cocoon Breaker, Gracious Gardener, ranging from the sublime Risen One to the ridiculous Water Jug.

Pallister’s word “diminishment” is perceptive. The person in these poems is small, diminutive, and waiting to attain full stature at a stage when her “wings / are too wide/ to become small/ again” (Spiritual Rebirth). “A tiny morsel of light” is “so large. you can hardly see” (“Humility”). She has strange names, Fly, Cocoon Breaker, Gracious Gardener, ranging from the sublime Risen One to the ridiculous Water Jug.

Some poems are little narratives, some are admonitions to the poet, who often finds herself in the presence of an unexpected audience of people waiting for her to make some sort of breakthrough. Many refer to a sudden opening: cracked open, punctured, torn open, unzipper, tear, rip, bursting, doorway, and of course empty tomb. “Whatever it is/ split/ the bark open/ chop the tree/ down.// The breath/ of God/ cannot come/ otherwise (“Thorny Breakthrough”).

The prose snippets are offered as companion pieces rather than explications for the poems and paintings, but they often falter. Syntax slips, participles dangle, and my editorial pen-finger gets itchy. Maybe this prose format is not simple enough for Sister Eileen’s mysticism. She would not be the first to wander down this path. My copy of the collected works of St. John of the Cross contains 740 pages; 26 pages is poetry (including his most famous “The Dark Night of the Soul”) and the rest is commentary. One returns often to the poetry, not so much to the prose.

In one of her early poems, read and sung on her CD, Eileen says, “Wisdom is something you cannot explain.” So maybe it is a mistake to try. Sister Eileen can write prose — witness her helpful “Introduction; the call of the artist and poet in religious life,” which tells all we need to know about her past, present, and future, except what we sense from the poems and paintings.

The choice of cover image is an enigma. It includes more details than other paintings, and the figure’s stance and garments are almost oriental. Eileen has named her “Closed Mouth Open” and concludes her poem: “You talk/ without talking!” Why choose an unrepresentative image to represent them all? Why not?

*

Phyllis Parham Reeve has written about local and personal history in her three solo books and in contributions to journals and multi-author publications. She also contributed the foreword to Charlotte Cameron’s play, October Ferries to Gabriola (Fictive Press, 2017). She is a contributing editor of the Dorchester Review and her writing appears occasionally in Amphora, the journal of the Alcuin Society. A retired librarian and bookseller and co-founder of the bookstore at Page’s Resort & Marina, she lives on Gabriola Island, where she continues to interfere in the cultural life of her community. More details than necessary may be found on her website: https://sites.google.com/site/phyllisreeve/

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Comments are closed.