#482 Two views of Raincoast Jews

Guide to Victoria’s Historic Jewish Cemetery

by Amber Woods

Victoria: Old Cemeteries Society, 2018

$15.00 / 9780968289945

Available at: jewishvictoria.wordpress.com/ordering/

*

Raincoast Jews: Integration in British Columbia

by Lillooet Nördlinger McDonnell

Vancouver: Midtown Press, 2014

$22.95 / 9780988110120

Both books reviewed by Sheldon Goldfarb

First published Feb. 9, 2019

*

*

Here’s a curious pair of books. One is a cemetery guide from Victoria, the first of a series, the publisher assures us. And it literally is a guide for walking around the tombstones, complete with a map and advice on Jewish burial customs.

Of more interest is its brief history of the early days of the Jewish community in British Columbia, focusing of course on how Victoria’s Hebrew Benevolent Society commissioned the cemetery, which was consecrated either in 1859 or 1860 (depending on whether you believe the text in the guide, which says 1860, or the photo of a marker reproduced in the guide, which says 1859).[i]

But of most interest is the tale of the first person buried in the cemetery, in 1861: Morris Price, a murder victim, killed by three Indigenous men while he worked in his shop surrounded by silver and gold. The attackers took the silver, but not the gold, and the author reports that the crime was “widely seen as an act of anti-colonialism.”

One wonders, though. A quick online search turns up no such statement of motive. One newspaper of the time simply said he was “murdered by Indians,” and some seem to have attributed the crime to theft or to a venting of “frustrations” over the death of the father of one of the perpetrators.

On the other hand, it’s true the area where Price was killed — not in Victoria, but on the mainland in what is now Lillooet — had been the site of the Fraser Canyon War between Indigenous people and white miners, so who knows?

In any case, poor Morris Price was transported to Victoria, where he was buried with both Jewish and Masonic rites. It is interesting that so many of these early British Columbia Jews were also Freemasons, a connection perhaps worth pursuing.

*

Lillooet Nördlinger McDonnell (author of the second book) does note the Masonic connection as part of her larger point that Jews in British Columbia integrated into non-Jewish society. To demonstrate her point, she singles out five individuals from different eras in a series of what she calls micro-histories, something of a cross between biography and sociology.

Her first example is Cecelia Davies Sylvester, one of those mentioned in the guide to the historic Victoria cemetery. The odd thing about her treatment of Sylvester is that she hardly talks about her; instead she uses her as a jumping off point to discuss the early days of Jews in B.C. And that’s okay; we can use a study of that. In fact, after that opening it is disappointing that she sticks more closely to her chosen individuals in her later chapters. Tell us more about the overall community, you want to say.

And was there much of a community? It is tempting to be carried away by the tales of how individual Jewish merchants made their way to the British Columbia gold rush to provide dry goods and the like to the pioneer prospectors, and there does seem to have been some of that. But there was community too. After all, there was that cemetery in Victoria, along with a synagogue and other Jewish institutions.

Still, Nördlinger McDonnell’s emphasis is on integration with non-Jewish society, though she does of course say there was a balance. The cover on her book is rather telling in this regard. Beneath the title, Raincoast Jews, is a picture of a B.C. landscape with not a hint of anything Jewish in it: all Raincoast, no Jews, one might say.

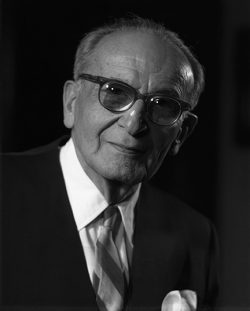

But in fact, though she has an argument to make about integration, her evidence seems a bit limited. She discusses Leon Koerner, for instance, the great benefactor of the University of British Columbia (which explains why the Koerner name can be seen in several places on campus).

“The Koerners were Jewish?” one thinks, mildly surprised. And yes, they were — sort of. They were pre-Holocaust refugees from Europe, and tended to emphasize their Czech rather than Jewish background, because they arrived in Canada at a time of heightened anti-Semitism, and several of them converted to Christianity, including Leon Koerner’s wife Thea and his brother Walter. Maybe even Leon himself converted; the evidence is unclear. But what is clear is that he devoted little of his time to the Jewish community.

And yet there was such a community. Though the recent history of Canadian Jews by Allan Levine[ii] suggested Vancouver was an outlier in comparison with Jewish history in Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg, what emerges from Nördlinger McDonnell’s work is that there were some similarities. As in the other centres, there was early immigration of Jews with roots in England and Germany who ended up in places like Vancouver’s West End and later in Shaughnessy and Point Grey. And then came Eastern European Jews, who moved into Vancouver’s Strathcona district, which seems to have been something like Montreal’s St. Urbain Street neighbourhood, the one celebrated in Mordecai Richler’s novels. If only Strathcona had produced its own Richler.

Nördlinger McDonnell’s other two recent examples are the violinist Harry Adaskin and the lawyer and judge, Nathan Nemetz. Both connected more to UBC and their professions than to the Jewish community, which tells us that they as individuals integrated into a non-Jewish world, but what of those who retained ties to the Jewish community? What was that community like? We still need a study of that.

But we can still learn some interesting facts from Nördlinger McDonnell, such as that David Oppenheimer, the Jewish mayor of Vancouver who founded the exclusive Vancouver Club in the nineteenth century, would probably not have been allowed to join it a few decades later because part of its exclusivity in the early twentieth century consisted in excluding Jews.

Vancouver in general, we learn from Nördlinger McDonnell, moved from a relatively open society in its early days to a more exclusive one in the dark days of the Depression and then moved again in recent times to being more open once more to Jews (and other minorities).

And we get a bit of a sense from Nördlinger McDonnell’s book about how open Jews could be about their Jewishness if seeking to integrate into non-Jewish society (not too open in the time of Koerner and Adaskin, more open for Nemetz).

Even Nemetz, however, did not identify very strongly with the Jewish community, in distinction even from members of his own family, who Nördlinger McDonnell describes as “community Jews.” It is those community Jews that it would be interesting to hear from.

Endnotes:

[i] Editor’s note: Amber Woods has contacted The Ormsby Review since publication to confirm that the date on the plaque is wrong and that her research makes it clear that 1860 was the date of consecration. She explains that the error on the plaque is probably a result of the fact that the land for the cemetery was bought in 1859.

[ii] Editor’s note: See Sheldon Goldfarb’s review of Allan Levine’s Seeking the Fabled City: The Canadian Jewish Experience (Toronto: Penguin Random House, 2018), in the Ormsby Review #452 (December 21, 2018).

*

Sheldon Goldfarb is the author of The Hundred-Year Trek: A History of Student Life at UBC (Heritage House, 2017). He has been the archivist for the UBC student society (the AMS) for more than twenty years and has also written a murder mystery and two academic books on the Victorian author William Makepeace Thackeray. His murder mystery, Remember, Remember, was nominated for an Arthur Ellis crime writing award in 2005. Originally from Montreal, he has a history degree from McGill University, a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba, and two degrees from the University of British Columbia: a PhD in English and a master’s degree in archival studies.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#482 Two views of Raincoast Jews”

Comments are closed.