#446 Comox Valley counterculture

Dancing in Gumboots: Adventure, Love and Resilience. Women of the Comox Valley

Lou Allison with Jane Wilde (editors)

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2018

$24.05 / 9781987915761

Reviewed by Susan Mayse

First published Dec. 13, 2018

*

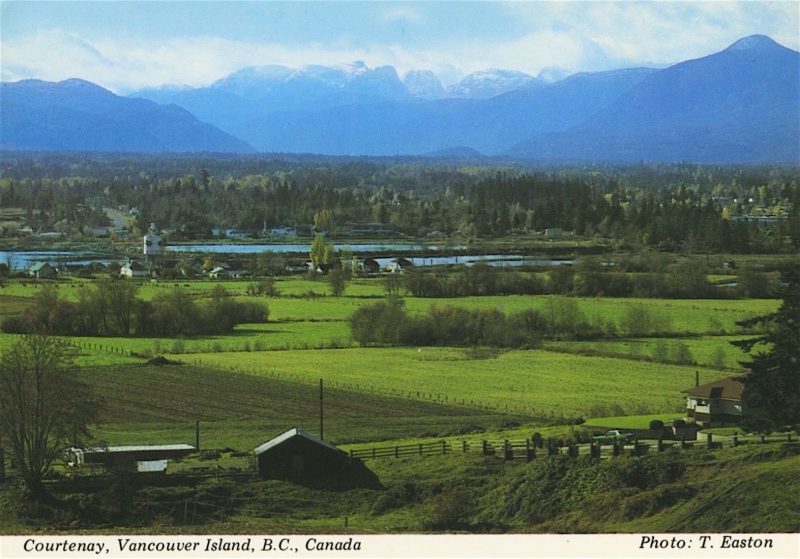

Mountains and glaciers glittered under a deep blue sky, fields and forests rolled all the way down to tidewater and a sheltered inside passage flourished with sea life. Maps and roadside signs carried names like Paradise Meadows and Abundance. Who could be blamed for thinking they’d landed in a heaven on earth? But by the 1960s, post-Second World War prosperity had thinned to a trickle, and the scattered communities of the Comox Valley looked increasingly weary. Fireweed and willow encroached the marginal farms, logging shifted farther upcoast, Cumberland’s last coal mine shut down after eighty boom-and-bust years, and tourism was chancy.

Mountains and glaciers glittered under a deep blue sky, fields and forests rolled all the way down to tidewater and a sheltered inside passage flourished with sea life. Maps and roadside signs carried names like Paradise Meadows and Abundance. Who could be blamed for thinking they’d landed in a heaven on earth? But by the 1960s, post-Second World War prosperity had thinned to a trickle, and the scattered communities of the Comox Valley looked increasingly weary. Fireweed and willow encroached the marginal farms, logging shifted farther upcoast, Cumberland’s last coal mine shut down after eighty boom-and-bust years, and tourism was chancy.

Into this slightly threadbare landscape arrived a generation of young women on their own or with partners, some of them avoiding the USA’s unpopular war in Vietnam. Students, children of the counterculture, young professionals, girlfriends and wives and mothers: they were bright, brave, talented, and passionate in their search for better ways to live.

A new book gathers thirty-two of their stories for the first time. Dancing in Gumboots, edited by Lou Allison with Jane Wilde — who moved south to Vancouver Island in 2016 — is a Comox Valley follow-on from their 2012 collection of essays by women on B.C.’s north coast, Girls in Gumboots.

It was a small migration, as migrations go. Some of the women first saw Vancouver Island on a summer trip to the West Coast and came back, months or years later, to stay. Others bought sight unseen. Farmable land drew them to Merville, Tsolum River, Dove Creek, and nearby Gulf Islands with books like Whole Earth Catalogue, Five Acres and Independence, or Stalking the Wild Asparagus in their backpacks.

They came from Montreal and Toronto and Vancouver and upcountry B.C., Chicago and San Francisco and New York, Britain and the Netherlands and France. Most were white, middle class, and educated. A few came from wealthy families that bought properties for them; one came from a Saskatchewan family whose graduation present to its teenagers was a set of luggage and a wave goodbye.

Photos from those days show smiling, long-haired, willowy young women in long skirts, standing near tipis or cabins. Some are in gumboots. Breaking land and building houses, for months or years they lived in vans, shacks, converted chicken sheds, or houses built by earlier pioneers. They combed second-hand stores and weedy junk piles for discarded hand-operated farm and household equipment gladly abandoned by an earlier generation and questioned their elderly neighbours for advice on crops, livestock, and canning.

Settling in the Comox Valley wasn’t always easy for the often underfunded and inexperienced young people, many from urban backgrounds. In her essay “Merville Musings,” Gerri Minaker describes a search for land in the Kootenays that would support intensive gardening. “It was all to no avail. Every hollow stump had several hippies living in it.”

In the Comox Valley she and her partner finally found a place. “In those days, we just assumed everything would work out.” It did.

Not everyone had a passion to turn the soil. Some discovered the centres of Courtenay, Comox, Union Bay, and the big-hearted old coal town of Cumberland. They made jam, made music, made families, and celebrated. They started and supported the Renaissance Fair, the Arts Alliance, the Filberg Festival, and several food co-ops. Volunteering, taking on gruelling jobs, studying, and training, over time they blossomed into determined women who could do just about anything with grace, humour, and savvy.

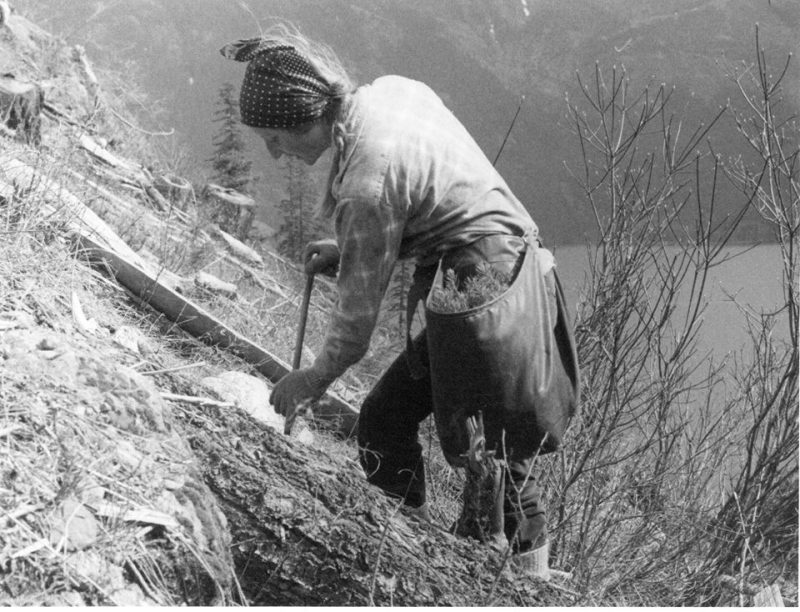

Just as the North Coast women of Gumboot Girls became fishers, loggers, and subsistence gardeners, the Comox Valley women became artists, teachers, nurses, midwives, farmers, gardeners, and tree planters, often persevering in a hostile male work environment. Pride in their accomplishments shines through their words.

“I had met some tree planters and knew immediately that was what I wanted to do,” Devaki Johnson writes in “I Kept Coming Back.” But like others, she first had to convince male crew leaders to hire women for the strenuous job she describes as heaven and hell. “I never thought I could plant a thousand trees in a day, which was necessary to keep the job. But I did.”

Gloria Simpson, another tree planter who broke the gender barrier, eventually became a contractor and foreman. In “All My Relations,” she writes that “Within a year, I was one of the highest-producing workers, and over the years I planted well over a million trees.”

Probably the best educated, most capable, and most confident generation of women seen so far in history, they took on the world and formed lifelong bonds of friendship and community. Some eventually left the Comox Valley; most stayed.

The overlapping pacifist, feminist, and back-to-the-land movements of the 1960s and 1970s — direct descendants of woman suffrage, forerunners of #MeToo and Time’s Up — offered motivation. Yet Lou Allison offers a caution in “Afloat,” her essay in the original collection, Gumboot Girls: “I didn’t set out to join a movement or become part of a trend: I simply cut myself loose from the moorings of my life.”

Many of their generation foresaw an imminent collapse of civilization, and these Comox Valley newcomers resolved to survive it in their hand-built houses with their own home-canned farm produce and their animal husbandry. They factored in homegrown pot, wild mushrooms, homemade wine, and a party for any occasion.

Some of their comments stand out.

“That summer I was living the dream,” Gerri Minaker writes. “Being a city girl, I had no idea what a turnip looked like in the ground, how parsley grew, when a pea was ripe for picking. Everything was a learning experience and an adventure.”

“The nights were starry and free of light pollution; the days were sunny and warm, or snowy, or rainy and cold. With not a neighbour in sight, it was like living in our own wilderness park,” Olive Scott writes in “Merville, My Home.”

Then there’s Nonie Caflish’s tale in “Building An Unexpected Life” of working one hot day clad only in sneakers and underpants. Avoiding sunburn, she put her underpants on her head as a hat — in time for old high school friends to drive up and wryly comment that they’d never expected to see quite so much of her.

Not all the adventures were rural. In “Embracing Change,” math teacher Linda Rajotte endearingly explains her love for her calculator. “With one simple keystroke, I could find values that were previously cumbersome to determine and at times could only be approximated through interpolation. My affection for calculators only got stronger as technology improved to include the use of graphing calculators.” Her teaching included calculus retreats and edible lessons illustrated with watermelon slices.

Many of the women look back with gratitude for their opportunity to experience life in a community of friends and in harmony with nature.

In “Re-membering,” Ardith Chambers reflects that, “As a young person, I believed that I could handle anything. Life proved me wrong, but in hindsight, I see more upsides than downsides …. Coming full circle, I see value in accepting life without question, but this time from the opposite side of innocence. I am confident everything will turn out fine. It always has.”

The predicted collapse of civilization didn’t occur in the seventies, but today, with climate change, alt-right violence, and political turmoil looming, let’s hope these Comox Valley women have kept their back-to-the-land skills sharp and their spirits willing.

If I were to wish for changes in the book, I’d have liked to see more mention of long-term residents of the Comox Valley: Ruth Masters, Wendy Kotilla, Melda Buchanan, women of old Merville and Cumberland families, Indigenous women, and those of other diverse backgrounds. Many of these became mentors to the women of Dancing in Gumboots.

Dancing in Gumboots, like the earlier Gumboot Girls, is an illuminating and entertaining read. The women’s individual stories are as diverse an assortment of voices as you’d expect: optimistic, practical, community-minded, moving, philosophical, often funny, and above all deceptively simple in their down-to-earth accounts of their younger lives.

Not only capsule memoirs, the essays also collectively reflect an era of sweeping social change that transformed Western society forever. The book will appeal especially to readers who were there, or wish they had been there, or want to cut themselves loose from the moorings of their own lives.

*

Vancouver Island writer and editor Susan Mayse writes fiction, nonfiction, and works in other genres. Her awards include the Arthur Ellis Award for true crime and the Edna Staebler Award for Creative Non-Fiction for Ginger: The Life and Death of Albert Goodwin (Harbour Publishing, 1990).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster