#413 Cuban saints and stones

Angela of the Stones

by Amanda Hale

Saskatoon: Thistledown Press, 2018

$19.95 / 9781771871655

Reviewed by Linda Rogers

First published November 3, 2018

*

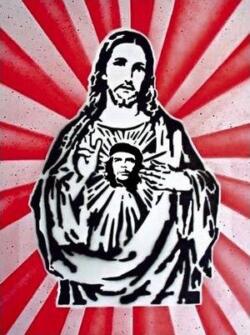

Appropriately, “La Huelga,” The Strike, the first story in the collection Angela of the Stones, begins with a raised fist, the collective slogan SEREMOS COMO EL CHE now applied to transforming Cuban religious practice, which includes the right to strike. Hale, clearly an aficionado, has enough familiarity to infuse her stories with loving clarity, the witness rebellion, starting with the ghost gestalt of “silent Fidel,” the formerly loquacious spirit.

Appropriately, “La Huelga,” The Strike, the first story in the collection Angela of the Stones, begins with a raised fist, the collective slogan SEREMOS COMO EL CHE now applied to transforming Cuban religious practice, which includes the right to strike. Hale, clearly an aficionado, has enough familiarity to infuse her stories with loving clarity, the witness rebellion, starting with the ghost gestalt of “silent Fidel,” the formerly loquacious spirit.

Fidel, raised in a Jesuit school, banished clerical hierarchies from the democratic republic established by his band of social reformers. By the time Viva Cuba Libre! shouted from every public wall, churches had been closed and refugee clerics, compadres of the old order that controlled ordinary Cubans with anachronistic religious practice and political oppression, had fled to Florida. The revolution was complete. Or so it seemed.

Because religion is in the deep structure (primary pre-revolution gestalt) of the Cuban psyche, its resurgence was inevitable, but the new religion, as revealed in this story of rebellion, has new articles of faith, and for Hale stones are the metaphorical rosary.

In choosing St Angela Merici, founder of the Ursuline Order of teaching nuns, for her allusive title, Hale draws inevitable parallels to the army of young revolutionaries who shared literacy with the camposinos in the early days of the revolution. Therein lies the irony of Cuba’s relationship to the Holy Mother Church, whose foot soldiers formed the infrastructure of evil in previous regimes, and in their current incarnation conformed to the Marxist doctrine of liberation theology.

In this story, the restored church endures a mini-revolution that parallels the political earthquake that changed Cuba forever. A good priest has been sent home for questioning the orthodoxies of church and state. This time the faithful, having transferred their devotion to the saints for adoration of the heroes of the revolution, are wearing T-shirts that say SEREMOS COMO EL CHE, we will be like Che, the new Jesus, and readers of these stories will suspend disbelief or not depending on their reaction to that prescription, a new hierarchy of angels and saints, some heroes of the revolution, some Orishas and some television evangelists broadcasting from America.

In this story, the restored church endures a mini-revolution that parallels the political earthquake that changed Cuba forever. A good priest has been sent home for questioning the orthodoxies of church and state. This time the faithful, having transferred their devotion to the saints for adoration of the heroes of the revolution, are wearing T-shirts that say SEREMOS COMO EL CHE, we will be like Che, the new Jesus, and readers of these stories will suspend disbelief or not depending on their reaction to that prescription, a new hierarchy of angels and saints, some heroes of the revolution, some Orishas and some television evangelists broadcasting from America.

Hale’s Angela is a street person, mad some would argue because the sane all have a place to sleep, but the sharp stones she picks up to defend herself carry the wisdom of the poet soldier Jose Marti, Patria es humanidad. As the least among the least, Angela of the Stones throws their own hypocrisy in the faces of those who, in their own agony of deprivation, have forgotten the gospel of kindness preached and practised by the deposed priest, as reported by the nurse Gertrudis fifty years after her soul was rocked by the first tremors.

Hale’s Angela is a street person, mad some would argue because the sane all have a place to sleep, but the sharp stones she picks up to defend herself carry the wisdom of the poet soldier Jose Marti, Patria es humanidad. As the least among the least, Angela of the Stones throws their own hypocrisy in the faces of those who, in their own agony of deprivation, have forgotten the gospel of kindness preached and practised by the deposed priest, as reported by the nurse Gertrudis fifty years after her soul was rocked by the first tremors.

There are no magic words to annihilate the pain of starvation during the Special Period when Russia abandoned its patriarchal transformation of Cuba into the land of cardboard bread, rubber cheese, and untunable pianos. Religion, the old antidote, and Patriotism, the new anodyne, are the volatile mortar connecting stone to stone.

There are no magic words to annihilate the pain of starvation during the Special Period when Russia abandoned its patriarchal transformation of Cuba into the land of cardboard bread, rubber cheese, and untunable pianos. Religion, the old antidote, and Patriotism, the new anodyne, are the volatile mortar connecting stone to stone.

“I remember,” they say, the ones who were there when their world transformed. Hale is faithful to their stories as they talk their way into the silence where all social dialectics expend their energy. This is the story of translated articles of faith, Jesus and Che enduring because martyrs have tickets to the Kingdom of Heaven as sainted ladies like Angela, God’s real gardeners, fade into the future unknown. Hale makes their case in stories that engage the head and the heart.

She finds her heroes in the rubble of organically constructed buildings that implode from the negative attention of bureaucrats swamped in pedantry. “A Limited Engagement,” reprises the hilarious 1966 comedy Death of a Bureaucrat, which follows the Byzantine path of a widow seeking her husband’s pension. In Hale’s story, a tourist dies and disappears in the usual tangle of red tape, as the writer takes the opportunity to manifest the leavening power of humour in a culture flattened by adversity, where Russian bidets were called “bidels” and a pantomimed beard substituted for the name of its leader.

She finds her heroes in the rubble of organically constructed buildings that implode from the negative attention of bureaucrats swamped in pedantry. “A Limited Engagement,” reprises the hilarious 1966 comedy Death of a Bureaucrat, which follows the Byzantine path of a widow seeking her husband’s pension. In Hale’s story, a tourist dies and disappears in the usual tangle of red tape, as the writer takes the opportunity to manifest the leavening power of humour in a culture flattened by adversity, where Russian bidets were called “bidels” and a pantomimed beard substituted for the name of its leader.

Tourism was the solution to the Special Period, when malnourished millions were forced to compromise, but it brought another version of explorers with smallpox, gold-chained, suntanned Canadian roosters with pockets filled with Viagra, STDs and much needed pension cheques.

Angela of the Stones is a transformative metaphor. Stones, sometimes a rosary, sometimes a broken road and sometimes a cairn built, rock on rock, are tokens of the idealism that not only sparked a revolution but has also kept the spirit of the people alive for longer than might reasonably have been expected, given the demise of the heretofore reliable Soviet Socialist Republic and the strangulating American blockade of Cuba.

These stories record the morphing of Cuban idealism to resigned pragmatism, as the government attempts to heal social deficits by educating unprecedented numbers of doctors and presenting the model of social and medical triage to the world. In her most overtly didactic story, “The Homecoming,” she deplores the public relations gesture of exporting the best doctors in international medical swat teams that gives the middle finger to America, but does not solve problems at home.

The stories “Daniela’s Condition” and “Berta’s Kidney” are metaphors for social malaise and the trembling infrastructure of church and family, as Cuban men struggle to find their dignity and Cuban women, burdened by millstones, are left to raise the children of infidelity. Hale, manifesting love and admiration especially for resilient Cuban women, doesn’t hesitate to reveal the cracks in the infamous sidewalks.

Take the beautiful promenade at your peril. The sea is beautiful, the women are beautiful, the sunshine is beautiful, but terror comes in nights without electricidad, darkened streets when the sun goes out.

Hale, the Witness, the present female guest in “The Unwelcome Guest,” pulls all the strands of detail and imagination, the layers of perception that make her narratives so insightful. She knows what can and cannot be said. The facile guest is required to notice the heroism of Cuba and it is only with the most intimate friends that darker truths are revealed. The revolution is not perfect. Fidel said he would shave off his beard when it was, when the possibility of Miami Cubans returning to a remembered status quo, the dream of Tito, the bitter narrator excoriating Obama for his entente with Raul Castro in “Miami Herald” would finally be laid to rest.

Hale, the Witness, the present female guest in “The Unwelcome Guest,” pulls all the strands of detail and imagination, the layers of perception that make her narratives so insightful. She knows what can and cannot be said. The facile guest is required to notice the heroism of Cuba and it is only with the most intimate friends that darker truths are revealed. The revolution is not perfect. Fidel said he would shave off his beard when it was, when the possibility of Miami Cubans returning to a remembered status quo, the dream of Tito, the bitter narrator excoriating Obama for his entente with Raul Castro in “Miami Herald” would finally be laid to rest.

Hale’s technique weaves from political to lyrical as she navigates her broken sidewalks, always reporting her peripheral vision, the shadowy sub-text of naïve idealism:

How the elements mirror us, he thinks. Soon it will be evening and everything will darken and disappear into the night, except for the crescent of a new moon and the stars so very far away. We’ll have to sit it out, he thinks, our time will come. But his next thought, rising like an alligator from the Zapata swamp, is that time is running out.

Angela kicks her stones down the road that leads she doesn’t know where. In the end, these stories are connected to that place where every Cuban family meets to share the sacraments of past and present, bread and hot peanuts in triangular newsprint sleeves, gestalt for the holy trinity sold by broken maniseros like the child genius Godofredo. Mani, the ubiquitous peanuts, are stones swallowed by a hungry populace.

As peanuts stand in for the bread of angels, holy sacraments are compromised in the struggle for survival. Church music, the under painting of this collection, is played on out of tune Russian pianos that conspire to ruin the ears of angel musicians, children born in a musical culture that perseveres and may eventually teach the world a lesson in dancing through the many veils of adversity.

As peanuts stand in for the bread of angels, holy sacraments are compromised in the struggle for survival. Church music, the under painting of this collection, is played on out of tune Russian pianos that conspire to ruin the ears of angel musicians, children born in a musical culture that perseveres and may eventually teach the world a lesson in dancing through the many veils of adversity.

Cubans are believers, for whom the blue sky familia is the model for survival on Earth, whether it be Catholic saints, Santeria Orishas or TV evangelists of the Pentecost broadcast from the Disney mainland across the Florida Straits, so close and yet so far away.

Hale captures the unity in Cuban multiplicity, her fiction true, embracing the humanity which is essential to the character of a country that remains a family defined by desperation, the promise of maybes that take so long whole generations grow old and die within the flimsy construct of a wish, like the screen dreams of the lovesick Yanelis, the betrayed child of “Firefly Park.”

Hale captures the unity in Cuban multiplicity, her fiction true, embracing the humanity which is essential to the character of a country that remains a family defined by desperation, the promise of maybes that take so long whole generations grow old and die within the flimsy construct of a wish, like the screen dreams of the lovesick Yanelis, the betrayed child of “Firefly Park.”

TV and computer screens that promise love and access to the regular comforts of toothpaste and toilet paper to the new generation Cubans are as unresponsive as the mirage of Brigadoon. As soon as they touch the dream, it disappears. This is the wisdom of Plato, its applications as elusive now as then.

*

Linda Rogers’ most recent book is a short story collection, Crow Jazz, from Mother Tongue Press (2018). Yo! Wik’sas? Hello! How Are You, a kids’ book in English and Kwak’wala based on the paintings of Kwakwaka’wakw artist Chief Rande Cook, from Exile Editions (Spring 2019), is next.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#413 Cuban saints and stones”

Comments are closed.