#299 The tough love of Seaweed

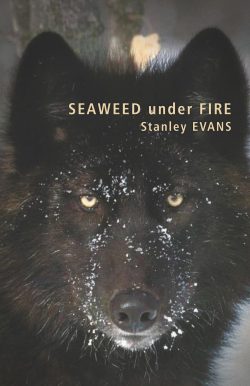

Seaweed under Fire

by Stanley Evans

Victoria: Ekstasis Editions, 2017.

$25.95 / 9781771711920

Reviewed by Phyllis Reeve

First published May 6, 2018

*

A hiker and his dog find a corpse in Beacon Hill Park.

Two cops find another corpse in an Italian restaurant.

Before long our provincial capital is littered with more dead bodies than Midsomer on the eve of Beltane.

[You can look it up-Ed.]

Our hero and narrator Detective Sergeant Silas Seaweed of the Victoria Police Department Crime Scene Investigation Unit arrives, finds clues, more bodies, several suspects.

Once again–for the seventh time–in Stanley Evans’ Seaweed under Fire, he confronts crooked lawyers, crooked policemen, crooked insurance salesmen, crooked restaurateurs, crooked green grocers moonlighting as moneylenders, even a crooked First Nations guy–and murderers.

The detective is Indigenous — but the author is not.

British-born, Stanley Evans has lived in Canada most of his life, had several careers, and written other books and plays prior to inventing Silas Seaweed in 2005. Searching the web I could not find any accusations of cultural appropriation directed at Evans. His work is sold and promoted by Strong Nations Books whose mandate promises to bring Indigenous books into our lives.[1]

“Sensitive” is an odd word to apply to writing so blatantly based on the Whodunit police procedural formula, but the deadpan narrative learned from Spade and Marlow permits Silas to treat everyone with the same nonchalant tough love — be they Coast Salish, Italian, Chinese, Filipino, or Caucasian. Silas’s heritage is always present, giving him a perspective useful in his dealing with others on the fringe. Incidents involving tradition and spirituality stop short of sentimentality.

Silas Seaweed has two residences: a container on the waterfront and a shack on the reserve, with a small outboard boat to take him between.

This is a man who rescues a large cedar log from the sea and builds a dugout canoe. He is a shape-shifter, changing effortlessly from someone who lives in a container to someone who goes for a drink at the Laurel Point Hotel and makes love to a beautiful billionairess.

A wolf and a racoon assist him in his sleuthing.

His boss Inspector Bernie Tapp regards Silas as the force’s “Indian specialist.” In the real world he would be less special; the Victoria Police Department has both currently serving and retired members who are First Nations. But this is not the real world.

His schooling was at Victoria’s prestigious St. Michael’s on a scholarship. Perhaps this equips him to confront two teenage girls in private-school uniforms smoking crack. The quintessential hard-boiled cop with a heart-of-gold, Silas is a do-gooder, welcoming regular walk-in clients at his office in the container. He does not like pimps, drug dealers, or men who beat up women.

He does like women — even colleagues, victims, and murderers. And women — even colleagues, victims, and murderers — like him.

Not all locales exist as Evans describes them, but he does try to remember to take advantage of attractive local geography; there are a few too many views of the Salish Sea, distant mountains and twinkling lights. Like most detectives of his ilk, he likes jazz but unfortunately when he tries to include a local star he gets her name wrong, so “the piano lady was playing Dianne Krall songs,” instead of Diana.

Sometimes style gets the better of him and he overdoes what, used once, might be an effective sentence structure. For instance, I found “My mentors were and still are shamans and hereditary chieftains” (p. 27), “Her town home was and still is a large red-brick Queen Anne-style house” (p. 42), and “Native Indians were and sometimes still are hunter-gatherers” (p. 47). And yes, he did and still does use both “First Nations” and “Indian.”

Some clichés just keep on giving. I won’t be giving away any plot secrets, even if I knew them, by quoting the conclusion of the novel: “I drove to Clover Point and parked in the turnaround. Looked out to sea and thought about Felicity Exeter. After a while I went to her house. She opened the door and said hello. She was wearing a turban to cover bandages around her head. That turban looked good on her.”

*

Phyllis Parham Reeve has written about local and personal history in her three solo books and in contributions to journals and multi-author publications. Recently she wrote the foreword to Charlotte Cameron’s play, October Ferries to Gabriola. She is a contributing editor of the Dorchester Review and her writing appears occasionally in Amphora, the journal of the Alcuin Society. A retired librarian and bookseller and co-founder of the bookstore at Page’s Resort & Marina, she lives on Gabriola Island, where she continues to interfere in the cultural life of her community. More details than necessary may be found on her website: https://sites.google.com/site/phyllisreeve/

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

[1] https://www.strongnations.com/