#257 Macdonald, Laurier, Borden

Prime Ministerial Power in Canada: Its Origins under Macdonald, Laurier, and Borden

by Patrice Dutil

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2017

$34.95 / 9780774834742

Reviewed by Barbara J. Messamore

First published March 2, 2018

*

Patrice Dutil seeks to lay to rest the pervasive notion that the prime minister’s office has become increasingly “presidential” in recent decades, that there has been an unprecedented concentration of power. He does so very persuasively. Dutil’s approach marries political science theory to political history, and includes instructive comparisons to the role of the American president.

Dutil intricately examines the role of prime minister through its first office holders and finds that, beginning with John A. Macdonald, incumbents set a template of tight administrative control, a pattern adopted by their successors. Dutil rejects the assessment of Macdonald as an indifferent administrator, and finds him instead to be highly competent in laying out the structure of cabinet in the 1867 shift from the pre-Confederation tradition of joint premiers.

Across party lines, subsequent prime ministers followed practices set in place at the time of Confederation, occasionally layering their own variations on top of this basic approach.

Dutil’s study of Wilfrid Laurier and Robert Borden reveals differences in prime ministerial style, but, by the time of Mackenzie King’s 1921 administration, “the office had solidified into an administrative and political granite” (p. 320).

The anomaly seems to have been Liberal Alexander Mackenzie, whose 1873-78 term formed an interlude in Macdonald’s domination of nineteenth-century politics. Dutil attributes Mackenzie’s manifest failures to the fact that he was a “mediocre administrator” (p. 67) who unwisely took on the demanding Public Works portfolio, chose isolated office space in Parliament’s West Block remote from critical ministries, and lacked Macdonald’s skill in tactfully stringing along seekers after government patronage.

Dutil shows an admirable grasp of historical context; this recourse to a deep reservoir of historical research allows him to actually test theories, assessing whether there is indeed any evidence of shifting practices in the office of prime minister. Such an approach also permits full consideration of the personal dimension in politics; Dutil creates a lively and compelling sense of each prime minister’s individual character. He chronicles their work habits and daily routines, even reporting what each ate for breakfast!

Their respective approaches to administration offer compelling portraits of character. Laurier and Borden each continued the Macdonald theme of centralized power. This did not mean that they surrounded themselves with non-entities. Dutil notes that Laurier in particular selected able and experienced administrators, preferring cabinet ministers who had been provincial premiers, accustomed to tough decisions.

Borden had had no cabinet experience when he took over the Conservative leadership. Dignified but humourless, prone to depression, Borden displayed little natural leadership and little aptitude for politics. He “suffered fools too gladly,” according to the editor of the Globe (p. 131). His reluctance to jettison Minister of Militia and Defence Sam Hughes was a case in point. Dutil’s lively and concrete political portraits are enhanced by his good eye for quotable material.

Dutil’s own background in public service affords him insight into the crucial role of non-elected civil servants. He stresses Macdonald’s reliance on a devoted cadre of carefully recruited deputy ministers, “a system that would allow for a highly centralized executive style” (p. 53). Dutil also chronicles decades of desultory reforms to the civil service to improve the quality of recruits and answer criticism about excessive patronage.

Tellingly, the prime ministers, while interested in improving efficiency, were loath to surrender the patronage opportunities inherent in the system. Joseph Pope, Macdonald’s secretary, complained about the “appalling trash” newspapers published about “the ‘evils of patronage,’” and questioned why control should be relinquished to “an inexperienced unrepresentative and irresponsible” Civil Service commission (p. 197).

The book provides year-by-year analysis of budgets as a means to determine prime ministerial priorities, and considers respective responses to crises. Among the administrative challenges faced by the prime ministers — then, as now — was policy for Indigenous people. It is not part of Dutil’s avowed goal to rehabilitate John A. Macdonald, whose historical reputation has suffered under accusations that he was the architect of Indigenous cultural genocide in Canada, but Dutil does provide detail that allows for a more nuanced assessment.

Some of Macdonald’s recent critics have even used the term “genocide” alone, implying a policy of not only eradicating Indigenous ways of life, but a systematic and deliberate destruction of the people themselves. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, in using the term “cultural genocide,” were essentially using the term metaphorically, to denote a demonstrable but failed federal government objective to force Indigenous people to abandon traditional practices.

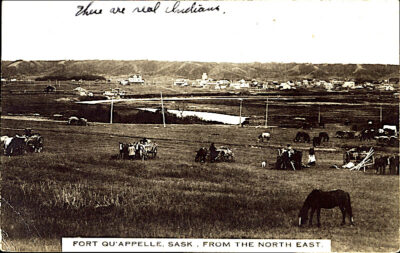

Dutil recreates the atmosphere of immediate crisis under which Macdonald acted — unwisely, as it proved, but in good faith. In the last winter of Alexander Mackenzie’s administration, some 75 Indigenous people died of apparent hunger and exposure at Fort Qu’Appelle, a tragedy brought on by the abrupt disappearance of the buffalo, compounded by disease and other scourges.

Macdonald was not alone in believing that assimilation was the only viable long-term alternative to starvation. Federal government schemes aimed at transforming Indigenous ways of life through agricultural instruction and industrial education were, we know with hindsight, abject failures. But the evidence reveals well-intentioned ineffectual actions, not any systematic attempt to do harm. Dutil revealingly notes a soaring expenditure in the budgetary line item for “Indians” in the period after Macdonald’s 1878 return to power. Macdonald boosted spending by a total of 181 percent in four years. In 1880-81, “after interest on the debt and infrastructure funding, ‘Indians’ was the government’s largest expenditure,” Dutil notes (p. 73).

One of the interesting features of the book is Dutil’s analysis of the rarely considered tool of Orders in Council. “For the student of power,” he explains, “OICs open a window on the gears of government as they officially command the civil service and set rules and regulations; they essentially convey the government’s will, without discussion or dissent” (p. 256). Much of cabinet’s business during its almost daily meetings was taken up with Orders in Council, and they reflect the prime minister’s goals.

One of the interesting features of the book is Dutil’s analysis of the rarely considered tool of Orders in Council. “For the student of power,” he explains, “OICs open a window on the gears of government as they officially command the civil service and set rules and regulations; they essentially convey the government’s will, without discussion or dissent” (p. 256). Much of cabinet’s business during its almost daily meetings was taken up with Orders in Council, and they reflect the prime minister’s goals.

Dutil compares OICs with American Presidential Executive Orders. The latter are more constitutionally debatable, yet Dutil draws attention to the profound foreign policy and domestic matters they have historically embraced — among them the Louisiana Purchase and Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. Dutil alludes to important measures covered by Orders in Council; to these might be added the entry of British Columbia into Confederation, as well as the joining of Prince Edward Island and the territory of Rupert’s Land.

Prime Ministerial Power in Canada is engaging reading. The book’s lively prose style, clarity of expression, logical and transparent structure, and meticulous attention to accuracy in detail adds to its appeal. It combines theoretical sophistication with profound historical understanding.

*

Barbara J. Messamore (PhD, Edinburgh) is an associate professor of history at University of the Fraser Valley. She is the author of Canada’s Governors General,1847-1878: Biography and Constitutional Evolution (University of Toronto Press, 2006), co-author of Conflict and Compromise: Pre-Confederation Canadian History (University of Toronto, 2017) and Narrating a Nation: Canadian History Pre-Confederation (McGraw Hill Ryerson, 2011), and editor-in-chief of the Journal of Historical Biography. Her articles on constitutional and political history have appeared in the Canadian Historical Review, the Journal of Parliamentary and Political Law, the Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, the British Journal of Canadian Studies and other journals.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Comments are closed.