#253 The divide of mountains and wine

Surveying the Great Divide: The Alberta/BC Boundary Survey, 1913-1917

by Jay Sherwood

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2017

$29.95 / 9781987915525

Reviewed by Robert Allen

First published Feb. 25, 2018

*

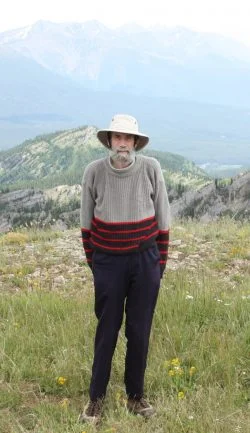

Retired teacher-librarian at Vanderhoof and past president of the Nechako Valley Historical Society, Jay Sherwood has provided nine indispensable – and overdue — histories and biographies of surveys, surveyors, and twentieth century explorers of B.C.

One of them, Surveying Southern British Columbia: A Photojournal of Frank Swannell, 1901-07 (Caitlin: 2014) was shortlisted both for the Roderick Haig-Brown Prize of the B.C. Book Prizes and the Lieutenant-Governor’s Medal for Historical Writing.

B.C. Land Surveyor Robert Allen notes in his review that after reading Sherwood’s story of marking the great mountainous divide between B.C. and Alberta, he has “a new and better appreciation of what was involved in determining our intricate eastern boundary.”

It’s a pleasure, therefore, to present this review of Jay Sherwood’s latest book, Surveying the Great Divide, coming at an unusual juncture in Canadian history when two normally civil provinces have been at loggerheads with one another over Alberta pipelines and B.C. wine. – Ed.

*

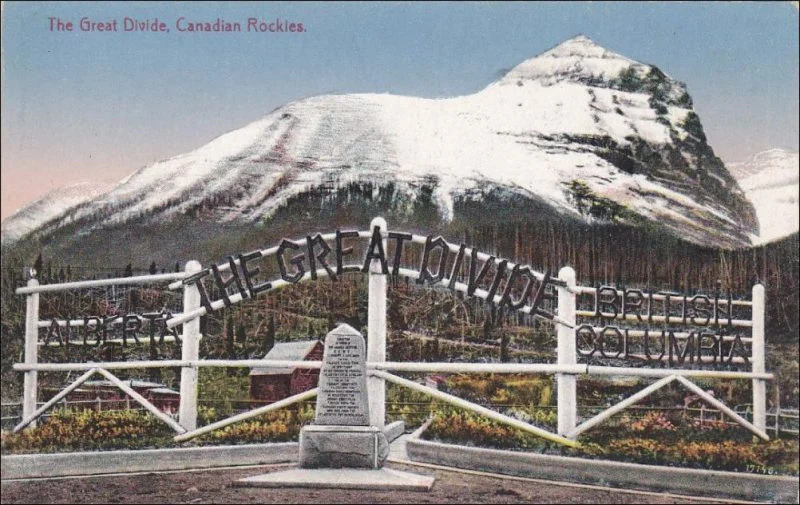

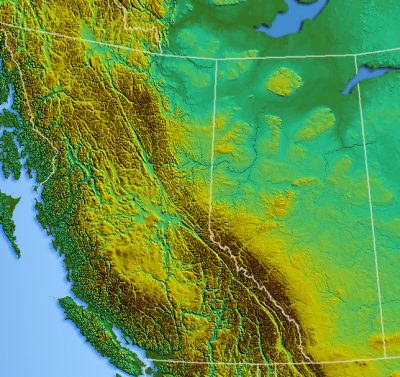

As with Jay Sherwood’s other books, Surveying the Great Divide ventures into often completely unexplored realms of British Columbia history. But while his previous books have for the most part been set in B.C., this one doubles as Alberta history. The surveying of the line between the two western provinces was no easy feat, and the 1,842 km boundary is the longest in Canada.

As with Jay Sherwood’s other books, Surveying the Great Divide ventures into often completely unexplored realms of British Columbia history. But while his previous books have for the most part been set in B.C., this one doubles as Alberta history. The surveying of the line between the two western provinces was no easy feat, and the 1,842 km boundary is the longest in Canada.

The boundary consists of two distinct parts. The northern section follows along a “man-defined” feature, the 120th meridian of longitude. The southern part, the focus of this book, follows along a natural feature, the Continental Divide — the spine of the Rocky Mountains, which was more commonly referred to as the Great Divide.

From the time that British Columbia became a province in 1871 until almost the end of the nineteenth century, the province was continually in debt. Very little money was allocated to surveying any boundaries, let alone the main eastern one. Sensitivity to the province’s extensive borders started to change with the Klondike gold rush of 1896-99, when the province’s northern and northwestern boundaries came into focus.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, the B.C. government also required more precise knowledge of its boundaries to regulate mining and timber interests and to encourage railway and mountain tourism in the Rockies.

Finally, in April 1912, Richard McBride’s government committed to surveying its eastern boundary. George Herbert Dawson, B.C.’s Surveyor General, contacted Edouard Deville, the Dominion of Canada’s Surveyor General, to discuss timing, methods of surveying, and cost sharing.

In June 1913, the Dominion, B.C., and Alberta governments agreed to a tripartite agreement to jointly fund the boundary survey. Each government appointed a commissioner: B.C. chose A.O. (Arthur Oliver) Wheeler, Alberta appointed Bill (Richard William) Cautley, and Deville selected J.N. (James Nevin) Wallace as Dominion commissioner.

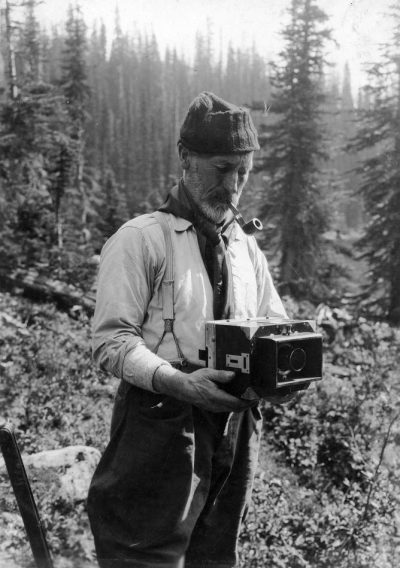

The three men met in Banff on June 9, 1913 to sign a memorandum outlining the organization of the survey and the scope of work. Wheeler, they decided, was to “be in charge of the topographical portion of the survey and the establishment of boundary monuments on the peaks adjacent to the passes.”

From Alberta, the memorandum continued, Cautley was to “be in charge of the surveying party required to take levels and make the preliminary survey of the boundary in the various passes and the erection of permanent boundary monuments therein.”

Federal representative Wallace, appointed to a part-time position as an advisor, was to check the accuracy of the work and arbitrate any disagreement between Wheeler and Cautley about the location of the boundary.

Now nearing the middle of June, the field parties organized quickly to get started on the project in a shortened 1913 field season.

Deville had previously listed the mountain passes that he thought should be surveyed. Chosen first was the Kicking Horse Pass, even though the Crowsnest Pass had the most economic importance. Kicking Horse, on the CPR mainline and accessible close to Banff and Calgary, offered the commissioners easy access by rail. Men and supplies were moved to the site easily.

Each Pass was designated a letter as it was surveyed. Pass A was Kicking Horse, Pass B was Vermillion, C was Simpson, and the list continued on to Pass S, the Yellowhead Pass.

The monument (or survey marker) set at the lowest point of Kicking Horse Pass was numbered 1A. All other monuments set going southerly were given odd numbers such as 3A, 5A, 7A, etc. Monuments set going northerly were given even numbers such as 2A, 4A, 6A, etc.

In this way a varied and precipitous terrain was simplified for survey purposes. As the remaining passes were surveyed, the same numbering system was retained, but the letter designated for the Pass was changed to B, C, D, etc.

Fortunately, a number of field party members kept diaries and careful field notes or described their progress in letters to family and friends. Many such documents have survived, and Sherwood has reviewed and drawn from them precise information about the surveys and conditions under which the crews worked.

The summer months featured snow, swollen creeks and rivers to cross, steep mountains to climb, extreme weather on the mountaintops, and sometimes difficulty finding gravel and water with which to make the concrete survey monuments.

Sherwood has gone through the documentary and photographic records meticulously to provide a detailed chapter for each year’s fieldwork from 1913 to 1917. Besides these five central yearly chapters, he provides chapters entitled Background, Cast of Characters, Surveying Methods, Geographical Names, Afterword, and Survey Crews. Rounding out the book are acknowledgements, a lengthy list of sources, and a useful index.

Required to take a “round” of photographs at each of his survey stations, Wheeler took nearly 2,000 of them, an astonishing record of mountain photography. Sherwood has incorporated a number of these in each chapter.

During this past decade, members of the Mountain Legacy Project at the University of Victoria http://mountainlegacy.ca/ have returned to some of Wheeler’s survey stations to compile a “before and after” photographic record in a technique known as “repeat photography.”

“The repeat photographs that they have taken,” notes Sherwood, “are being used by scientists to document a variety of changes that have occurred in the landscape during the past century.” Sherwood also uses his own repeat photographs throughout the book.

For example, in the summer of 2017, a large wild fire burned in the Akamina Pass, altering its landscape and ecosystem. Between the original photographs taken by Wheeler and Cautley, and recent ones by the Mountain Legacy Project and Sherwood, scientists will be able to document the regeneration of the ecosystem and a century of landscape change in this scenic location.

The boundary survey coincided with the worst part of the First World War. “Despite the rugged terrain, financial restraints caused by World War 1, and the shortage of qualified personnel,” Sherwood concludes, “A.O. Wheeler, R.W. Cautley and their assistants succeeded in producing an accurate survey and maintaining the project during these five difficult years.”

Later, from 1918 to 1924, the impressive and resolute Wheeler – whose son Edward Oliver Wheeler simultaneously took part in the first topographical survey of Mount Everest in 1921[1] — added to the survey of the Great Divide, while Cautley moved further north to survey the 120th meridian from the Great Divide through the Peace River area. Cautley’s later work could probably fill a book of its own.

I well recall my own experience of these Rocky Mountain passes. In February 1968, I moved from the coast to Fort St. John to work. I still remember being awestruck as I drove through the Pine Pass in my first experience of the Rockies.

While the Pine Pass isn’t near the B.C.- Alberta boundary, the mountains are nearly as massive as those that Wheeler and Cautley worked in. While living in Fort St. John, I drove across the 120th meridian on numerous occasions for work and pleasure.

In later years, I have driven across our southern border, the northern boundary with the Yukon, and the north western boundary to follow the Yukon Gold Rush trail — but I am still spellbound every time I drive through the Yellowhead, Kicking Horse, Vermillion, or Crowsnest passes.

Having read Surveying the Great Divide, I am awestruck by the hardships involved in surveying that border and full of admiration for the detailed fieldwork of a century ago.

We have all driven by signs saying, “Welcome to Alberta” (and “Welcome to British Columbia”), and at least for me, I will have a new and better appreciation of what was involved in determining our intricate eastern boundary from high elevation survey stations in mountains that had never or only very recently been climbed.

Indeed, on my next journey through one of those passes, I will stop and tip my hat to Wheeler, Cautley, and their crews.

Thank you, Jay Sherwood, for putting this book together to commemorate these fine surveyors on our great country’s 150th birthday — and on the 100th anniversary of the completion of the survey of this tangled mountainous portion of the B.C.- Alberta boundary.

*

Robert Allen is a Life Member of the Association of British Columbia Land Surveyors (ABCLS), a Life Member of the Canadian Institute of Geomatics, and a Canada Lands Surveyor. A past president of both the ABCLS and the Association of Canada Lands Surveyors, he has also served as the chair of the ABCLS Historical and Biographical Committee for the past 25 years. Raised in Courtenay, he has spent most of his working career in Sechelt. Now retired from active practice, he remains active in Sunshine Coast Search and Rescue (Team Leader and Treasurer), the Sunshine Coast Lions Club (Past President), and the Sunshine Coast Lions’ Housing Society (President). This latter society runs a $20 million, soon to be $40 million, subsidized housing complex in Sechelt for Seniors and others with disabilities.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg — BC BookWorld / ABCBookWorld / BCBookLook / BC BookAwards / The Literary Map of B.C. / The Ormsby Review

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

Endnotes:

[1] For the equally impressive younger Wheeler, see Wade Davis, Into the Silence: The Great War, Mallory, and the Conquest of Everest (Toronto: Knopf Canada, 2011).

Comments are closed.