#252 We came, we saw, we skated

First published Feb. 24, 2018.

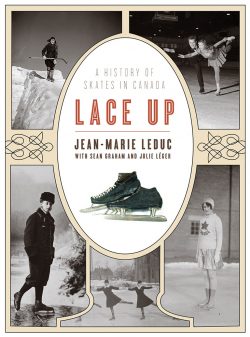

Lace Up: A History of Skates in Canada

by Jean-Marie Leduc, with Sean Graham & Julie Leger

Victoria: Heritage House Publishing Company, 2017.

$19.95 / 9781772032277

Reviewed by David Mills

*

A photo near the start of Lace-Up: A History of Skates in Canada will be familiar to many Canadians. It shows a boy in Quebec City, standing in his skates, perhaps his first pair, wearing a hockey uniform and holding a stick.

A photo near the start of Lace-Up: A History of Skates in Canada will be familiar to many Canadians. It shows a boy in Quebec City, standing in his skates, perhaps his first pair, wearing a hockey uniform and holding a stick.

I remember a similar photo of me on a small pond on my grandfather’s farm in Ontario, in a Toronto Maple Leafs’ toque and sweater and wearing my first pair of skates, imagining that I was Tim Horton. I couldn’t tell you the brand of the skates, but I remember the joy of putting them on for the first time, having my father tie them up for me, and walking out to the pond to skate — badly. But it was not the fault of the skates. Since then I have had many pairs of skates, most of them purchased second- or third- hand for the beginning of another hockey season.

Now as an adult, I buy new goalie skates for old-timers’ hockey. In the 1970s, these were quite heavy because of the hard, plastic protective cowling around the boot, while my last pair of goalie skates, purchased less than ten years ago, were much lighter while providing the same protection and featuring grooved “cheaters” on the toe to allow a goalie to push off while in the butterfly.

Now, a new pair of Bauer goalie skates, like the ones Henrik Lundqvist wears, have no protective shell at all. And they are no bargain at $750.

It was always a treat getting new skates. My sisters, who figure-skated for a winter or two, might have felt the same. I am sure they imagined themselves as Barbara Ann Scott, the winner of an Olympic gold medal in 1948, in their bright, white skates.

I read this short book, Lace Up: A History of Skates in Canada, with much interest. Author Jean-Marie Leduc, identified as “the world’s foremost authority on skates,” has 367 pairs in his collection. They range chronologically from bone skates worn by Indigenous peoples some 10,000 years ago to a pair of Barbara Ann Scott’s autographed skates and those of former NHLers, Emile “Butch” Bouchard and his son, Pierre.

Jean-Marie Leduc’s unparalleled collection has been exhibited at venues such as the Canadian Museum of History, the Hockey Hall of Fame, and the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver. This man has a very healthy Canadian love affair with skates and skating.

Leduc was active in Ottawa’s speed skating community and his son, Jean-Francois Leduc, was a nationally recognized speed skater. Jean-Marie was also an in-house announcer for short-track events, including the 2002 Olympics in Salt Lake City.

Short chapters describe how skates function, provide histories of early Indigenous bone and wooden skates worn in Canada, Finland, and elsewhere, and take the reader up to the first metal skates developed in Europe over 500 years ago. Separate chapters deal with figure, speed, and hockey skates, each with numerous photos and illustrations that show how they have changed over time.

I learned much I hadn’t known. Skating on wooden or bone blades was more like skiing. Poles, rather than the movement of the skates, provided propulsion. With the invention of metal blades, the style of skating became more like that of today. Leduc also provides a cultural history of skating in fifteenth century Holland, although some of the most famous paintings are not included in the book.

Leduc and his co-authors Sean Graham and Julie Leger also consider skates in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when they became accessible to most Canadians. They have gone to great lengths to discover their provenance – when and where they were made and the manufacturer. For example, Acme Club skates, affixed to a shoe, were made in Halifax at the time of Confederation. But Leduc also includes skates made by blacksmiths in small towns workshops.

The figure skate section explains their evolution, with blades attached directly to the boots and with stop picks and thicker blades to allow for jumping, which revolutionized the sport. This discussion is rather short and ignores the gendered aspects of figure skating, which many people continue to see as an activity primarily for girls.

The ubiquitous white figure skates reinforced the idea that figure skating was a feminine sport: not many boys figure skated in the twentieth century.

It is interesting to note that only one NHL team, the California Golden Seals, ever wore white skates. This incongruous sight resulted from pressure from the American owner, Charles O. Finley, to mimic his baseball team, the Oakland A’s.

Nor, at first, was figure skating seen as a properly masculine activity. Kurt Browning, for example, has admitted that he had “to endure the social taboo of participating in the sport.” It was not regarded as an activity that “turned boys into men” or emphasized heterosexual masculinity. Some skaters, like Elvis Stojko, compensated by appearing to be hyper-masculine.

It might have been useful for the professional historians, Sean Graham and Julie Leger, who assisted Leduc, to address these larger cultural issues and explore themes of gender and sexuality. Mary Louise Adams’ excellent book on the subject, Artistic Impressions: Figure Skating, Masculinity, and the Limits of Sport (University of Toronto Press, 2011), comes to mind.

Leduc’s love of speed skating is especially clear in his chapter on that sport. Again, the evolution of speed skates is described, with the blades and boots becoming higher so that skaters could lean into the turns. Leduc also notes the emergence of short-track skating and the re-design of the clap skates (invented in the nineteenth century) for long-track skating.

With clap skates, the heel comes up so the blade remains on the ice longer. Skaters like Catriona Le May Doan had to adapt their styles to the new technology if they were to succeed.

The chapter on hockey skates is a little disappointing. Leduc does not consider goalie skates. He discusses hockey skate evolution from the invention of tube skates to the introduction of the Tuuk blade, which used plastic to attach the metal blade to the boot; the plastic is hollowed out to make the skate lighter. Metal blades are now covered with layers of carbon.

Bauer came up with a “trigger blade” which could be removed from the plastic holder and replaced with a new, sharper blade. Skaters’ boots are now moulded to the foot of the player by the application of heat, and blade angles are adjusted to maximize performance (it is not simply done by eye as it was in the 1950s, illustrated by the photo on page 14), allowing a Connor McDavid to skate at speeds approaching 40 km/hour in an NHL game.

The author might wish to add the new Bauer Supreme 1s that uses titanium and memory foam for a light, fitted skate. The price for this pair of skates? Just $1000.

But advances in skate technology are not always linear. Lange, the maker of ski equipment, branched into plastic skate boots, modelled on its ski boots. While the plastic boot provided protection, there was no give in them. Awkward falls sometimes resulted in broken legs. Lange no longer makes skates.

In 2007, Thermablades, which were endorsed by Wayne Gretzky, appeared. They came with a rechargeable battery and microprocessor to maintain a blade temperature of 5 C. This heat was to melt ice, reduce gliding friction, and reduce skaters’ starting resistance. When they were tested, NHL players did not notice an appreciable difference and the skates did not become popular. A pair of these heater skates, which once sold for $400, can now be picked up for under $40.

Lace Up also notes the growing popularity of sledge hockey and the use of skate technology to improve the sledges. It’s too bad that Leduc did not include the amazing story of a member of the national sledge hockey team, Kieran Block from Edmonton, who shattered both legs in a diving accident.

Block, who played in the Western Hockey League and for the University of Alberta Golden Bears before the accident, was introduced to sledge hockey and excelled at the new sport. In spite of the damage to his legs, eventually he learned to skate on them again and is currently playing Senior AAA hockey with the Stony Plain Eagles. He skates more easily than he can walk. His skates might eventually be a worthy addition to Leduc’s collection.

While Lace Up contains much fascinating content and a narrative nicely complemented by photos and illustrations, the book really only focuses on the skates in the Leduc collection, impressive as they are, rather than on the larger history of skates in Canada, as the title suggests.

Despite its slightly restricted point of origin, I would recommend seeing the Leduc collection in person when it is exhibited in the future and buying Lace Up: A History of Skates in Canada as a guide and keepsake. This is a book, to quote Joni Mitchell, to skate away on.

*

David Mills is now retired from the Department of History & Classics at the University of Alberta where he taught Canadian history and sports history. He has written several articles on the business of hockey and is currently co-authoring a book on the new arena in Edmonton. He coached both his son’s hockey teams and daughter’s ringette teams and spent many weekends in

arenas around Alberta; he is also the former President of the International Ringette Federation. He was a goalie in old-timers’ leagues in Edmonton and is quite familiar with skates due to the hundreds of times he has had to tie them over his less than stellar career.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie\

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg — BC BookWorld / ABCBookWorld / BCBookLook / BC BookAwards / The Literary Map of B.C. / The Ormsby Review

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster