#185 Diversity of immigrant women

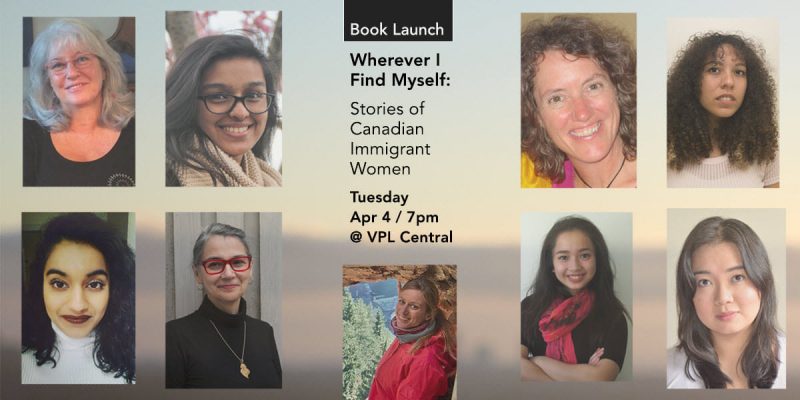

REVIEW: Wherever I Find Myself: Stories by Canadian Immigrant Women

By Miriam Matejova (editor)

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2017.

$24.95 / 978-1-987915-34-1

Reviewed by Gillian Der

First published October 21, 2017

*

The third anthology in a series on Canadian women published by Caitlin Press, Wherever I Find Myself, edited by Miriam Matejova, is a collection of non-fiction essays written by immigrant Canadian women.

This striking collection of truths crosses lines of class, race, and sexuality to detail a few of the infinite ways immigrant women define themselves, and invites the reader into the intimate experiences of 24 women who are also the book’s contributors.

Matejova expertly introduces this collection against a backdrop of an increasingly isolationist world and insists that, more than ever, we need the compassion, listening skills, and these women’s varied experiences to stand against rising xenophobia. By placing their stories within a political frame, Matejova calls on the reader to challenge stereotypes of immigrants, deeply held ideas of citizenship and belonging, and to think critically of how the Canadian state and society both support and fail these women.

To confront those stereotypes, Matejova curates a space where we are asked to think of immigrant experiences as plural. This anthology offers space for these women to express their agency and to represent themselves and their experiences.

Although Wherever I Find Myself provides sharp instances of the kinds of change that characterize immigration, such as the sight of family members waving goodbye, or the typical temperature shock of a Canadian winter, these stories also imagine immigration as a lifelong process. This is accomplished in some stories by contemplating the effects of migration within a family as the contributors share remembrances of home and work, and as they expand on the idea of immigration across generational lines.

For example, Esmeralda Cabral in “The Pull of the Azores” tries to connect her children to the town she grew up in; and Sarah Munawar, in “How to Emerge from the Belly of the Whale,” recounts a daughter trying to comprehend her father’s search for familiarity in the landscape of the Rocky Mountains.

In these instances, the focus moves beyond the all-to-common immigration narratives of insecurity, hardship, and vulnerability to ask the reader to consider immigration in its plurality and question who is impacted by immigration — and who is the immigrant to begin with.

The task of exploring immigration in its plurality also led me to ask what defines Canadianness — and if it even exists. The contributors to Wherever I Find Myself grapple with belonging and finding a place for themselves, if there is one, in the Canadian nation.

In “Border Crossing,” NikNaz K. provides instances of racism and discrimination resulting from how she presents her gender. These served to exclude K. from the Canadian nation and created a deep rift in the conception of Canada as a liberal, multicultural, and tolerant nation. NikNaz is caught in an intermediate state between an exclusion she feels from racism and gender expectation and being called out as a bad Muslim for her sexuality.

This feeling of “belonging nowhere” directly challenges the construction of Canada as a place where everyone can belong.

Stories like NikNaz’s demonstrate how empty the idea of diversity is unless we are committed to learning and honouring that diversity. Diversity for its own sake will never work to create a space within Canada for marginalised peoples. Instead, we need diversity for the possibility it holds. Different lived experiences offer new perspectives on tackling the challenges we face as a nation, such as the racism, sexism, and homophobia explored by NikNaz. We must listen to these differences and take them into ourselves as a chance to reflect on what it means to be Canadian.

As a second-generation Chinese immigrant, I found my attention was held cover to cover. I wanted desperately to find something out of place in this anthology, something lacking or left unsaid. Instead, the authors of these essays spoke honestly and with deeply powerful voices about a process that has been both central to my own being and that has too often been obscured from my learning. Wherever I Find Myself creates a space for reflection on the experiences of my own family and on how immigration shaped and continues to shape me.

I do wish there had been more stories here from Canada’s north and more commitment to the inclusion of refugee stories, but I understand that this anthology was intended as a small sample of Canadian immigrant women’s experiences.

This powerful anthology is desperately needed as we work to define and redefine Canada in these uncertain times.

*

Gillian Der is a youth climate justice activist working on watershed consciousness in the Salish Sea Bio-region. She comes from a strong line of activist mothers who have lived in British Columbia for five generations and campaigned for social justice in their own communities. She also acknowledges her ancestors who built railways, community, and finally prosperity after an intergenerational migration from Southern China. Gillian studies geographies and is increasingly interested in the ways place shapes who we are, especially in the context of social movements and environmental justice. In her time away from community organizing, Gillian can be found interacting with the waters, mountains, and forests that sustain us.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg — BC BookWorld / ABCBookWorld / BCBookLook / BC BookAwards / The Literary Map of B.C. / The Ormsby Review

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster