#170 Midwifery, bongos & blue boxes

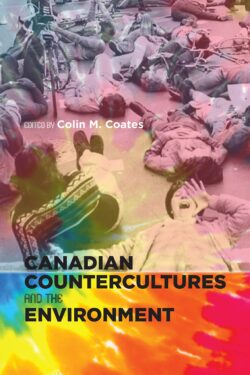

Canadian Countercultures and the Environment

Colin M. Coates (editor)

Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2016

$34.95 / 9781552388143

Reviewed by Lauren Harding

First published September 17, 2017

*

I read the last pages of Colin Coates’s edited collection while lying on Vancouver’s infamous Wreck Beach. Around me fresh University of British Columbia undergraduates gawked at the spectacle of the clothing-optional beach right next to campus and older beachgoers grumbled at the yachts blasting music offshore.

I read the last pages of Colin Coates’s edited collection while lying on Vancouver’s infamous Wreck Beach. Around me fresh University of British Columbia undergraduates gawked at the spectacle of the clothing-optional beach right next to campus and older beachgoers grumbled at the yachts blasting music offshore.

The naturist Wreck Beach Preservation Society started their advocacy for clothing-optional beach culture in Vancouver in 1974. The nudity, drugs, and bongo drums of Wreck feel like something of an anachronism under the forest-fire fuelled haze of 2017. Yet it was the perfect setting to reflect on both environmental issues and the legacy of Canada’s counterculture of the 1970s.

Canadian Countercultures and the Environment is a historical research collection edited by historian Colin Coates of York University. It focuses on a variety of anti-establishment social movements from the late 1960s to the early 1980s. The collection emerged from a workshop which all of the authors attended on Hornby Island in 2011, organized through the Network in Canadian History & Environment (NiCHE), which in turn was sponsored through a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

These details may appear somewhat superficial, but they give insight into the atmosphere in which the key themes of the volume must have taken shape. Like the collection of authors, many of the countercultural movements discussed were made up of diverse individuals who shared common interests, made use of government funding to explore “radical” ideas (or the history of them), and came together in a particular place in a particular time. The significance of locale, the use (or depending on political orientation, misuse) of state funds, and the importance of finding commonality despite diversity all feature prominently as themes throughout the collection.

The volume is divided into two sections, the first titled “environmental activism” and the second “people, nature, activities.” The divide somewhat works, although there is overlap between the two. It would also be possible to divide the book into sections on British Columbia and the rest of Canada. With five out of the eleven chapters focused on British Columbia, the collection is, perhaps, too B.C.-centric to really represent a national history of countercultures of the environment.

The over-representation of British Columbia is no surprise, as British Columbia was, as is clear from the histories in this volume, an important centre for countercultural movements in Canada. However, with no examples of counter-cultural movements from the prairie provinces or the Maritimes, with the exception of P.E.I., one would think that these regions of Canada are the conservative heartlands that they are often represented as. Such B.C.-centrism is expected, but also a little unfortunate.

Although there is some repetition in the regional focus within the collection, the keen focus on the local nuances in each setting renders each of the essays individual. Nancy Janovicek, Kathleen Rodgers, and Megan Davies all focus on one region of British Columbia, the Slocan valley.

Janovicek and Rodgers both focus on opposition and alternatives to industrial resource management, with a focus on forestry and mining respectively. Davies’ piece, despite being based in the same regions as the others, takes on a different subject from any other in the collection and discusses the home birth movement. Her detailed account of midwifery and community is fascinating in a large part because of the detailed oral history interviews Davies undertook for this research.

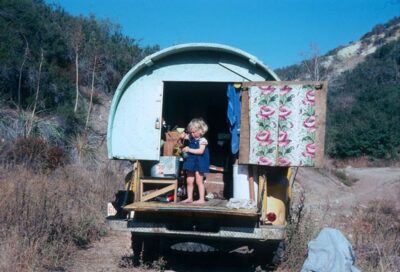

Overall, a strength of the collection is the incorporations of biographies of particular individuals as the “face” of the movements. For example, the chapters by Sharon Weaver and Matt Cavers both give insights into some of the characters who both participated in and opposed back-to-the-land movements. Weaver and Cavers both focus on well-known hubs for the back-to-the-land movement in British Columbia, Denman Island and the Sunshine Coast respectively.

Although each of the contributors takes pains to connect the local actions under discussion to wider, global countercultural movements and growing social awareness of environmental issues, it is the use of individual oral histories and local archives that make these histories Canadian. Each is firmly located in a particular place, which is fitting in a collection that explores actions that were in many ways, despite connections to larger social movements, truly “back-to-land” and “grassroots” in character.

However, the strongest pieces in the collection are actually those that focus on countercultural movements outside of British Columbia. David Neufeld’s research on the Yukon is particularly striking because he presents a portrait of a counter-cultural movement that does not fit the expected mould. Also fascinating are Alan MacEachern and Ryan O’Connor’s oral histories of growing up back to the land on Prince Edward Island.

Furthermore, both Neufeld and MacEachern’s pieces ask nuanced questions about identity within countercultures, the former with a focus on settler-Canadian and aboriginal relationships within and without the environmental movement, and the latter by focusing on children’s senses of belonging in rural communities.

A lack of geographic diversity is only a mild flaw in an edited collection that relied on contributors responding to a call, but it does make the collection feel somewhat uneven in its focus. It also allows those accounts that do not focus on the stereotypical lotus-lander to add a necessary complexity to our understanding of who was involved in the Canadian countercultures of the 1960s-1980s.

A connecting thread throughout the collection, and perhaps what renders these examples of counter-culture rather uniquely Canadian, is the relationship between the movements and the government, particularly the Liberal federal government of Canada in the 1970s and early 80s.

This connection between local environmental activism and state-sponsored initiatives such as the Local Initiatives Program (LIP) is apparent in every case discussed throughout the volume. Henry Trim’s chapter on the Ark project on PEI particularly stands out: in its execution it was almost more a state initiative than a local, countercultural one. The ironic intertwining of state support and countercultural actions, from community forests and youth grants, to futuristic habitats like the Ark is a fascinating common thread in the history of the environmental movement in Canada.

Notable too is the insistent tracing of the legacies of countercultural movements in each chapter. In his introduction, Coates observes that many of the critiques these movements made of mainstream culture, at least in regards to environmentalism, have transformed into attitudes accepted by the mainstream.

Another strength, visible in several of the essays, is the connection between these movements and the everyday life of Canadians at this particular moment in history. Perhaps the most recognizable is Ryan O’Connor’s history of recycling and his detailed discussion of the origins of the ubiquitous blue box. Another is Daniel Ross’s tracing of the history of cycling activism in Montreal and the contemporary

Coates’s collection will be of interest to those who wish to know more about Canada’s back-to-the-land movement of the late twentieth century, which was the dominant countercultural movement discussed in this text. This collection tries to answer the often-asked question “what happened next?” in its focus on the legacies of environmental activism from this era. Rather than emphasizing the eventual failures of the utopian dreamers of the Canadian ‘hippie’ movement, the histories in this collection show the complex nature of each movement’s make-up, and how rather than “failing,” many of them simply, like most social movements, either shifted in orientation or dispersed both their people and ideas into wider society.

*

Lauren Harding is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of British Columbia in the Department of Anthropology. Her dissertation research was conducted on Huu-ay-aht and Ditidaht territory on the west coast of Vancouver Island in Pacific Rim National Park Reserve. She is writing a cultural history of the West Coast Trail, with a focus on settler-Canadian recreation practices as a form of nation-building and the intersection between different cultural conceptions of wilderness and territory in the context of settler-colonialism. In other words, she studies hiking and camping! Her areas of academic interest include space and place theory, the anthropology of colonialism, environmental history, Canadian studies, and the anthropology of tourism.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster