#148 Pacific Theatre almost homeless

ESSAY: Theatre in Vancouver Today: A Paradox

by Carol Volkart

First published July 8, 2017

*

Everything about the Pacific Theatre is modest — from the low-ceilinged lobby with its island of couches around a coffee table, to its urns of self-serve coffee (regular or decaf), to its 128-seat alley-style theatre where a spectator who needs to leave during a performance must be ushered right across the tiny stage.

But the safe haven the Pacific Theatre Company has enjoyed in the basement of the Holy Trinity Anglican Church since 1994 is coming to an abrupt end, thanks to Vancouver’s ever-soaring real-estate market. When bulldozers move in next June to redevelop most of the 12th and Hemlock church site for condominiums, the Pacific Theatre will face higher costs and a riskier future as it tries to survive in one of the most expensive cities in the world.

It’s a curious time in the history of theatre in the city. On the one hand, there are problems finding affordable performance space and worries about a flood of artists leaving the city for cheaper communities. On the other hand, theatre is thriving like never before in Vancouver, longtime theatre historian, actor and critic Jerry Wasserman said in a spring 2017 lecture at Simon Fraser University.

There are glittering new facilities, such as the BMO Theatre Centre at 162 West 1st, with their polished bars and modern glass exteriors. The Arts Club, one of the BMO’s tenants, had a budget of $16 million and attendance of 255,000 last year compared to $150,000 and an audience of 29,000 in 1972, Wasserman wrote in a February story in The Vancouver Sun. (Wasserman, 2017).

In a subsequent email interview about the theatre scene generally, Wasserman continued, “There are certainly more theatre companies, more theatre venues, more performances, and a longer theatre year than ever before in the history of the city and region.” He credited population growth, high-quality theatrical work and “a relatively affluent, educated population that is willing to spend money on culture” for the boom.

But, like fellow academic Peter Dickinson and the Pacific Theatre’s marketing director Andrea Loewen, he has concerns about theatre’s future in Vancouver. “The paradox — and the danger — is that theatre is thriving here despite the increase in cost of living that sooner or later (maybe sooner) will definitely have an effect by driving out artists who can’t possibly afford to live here,” he said.

The affordability crisis isn’t the first challenge Vancouver’s theatrical community has faced since the city’s earliest theatres emerged in the late 1800s. Recessions, depressions and changing entertainment tastes have seen theatres and companies popping up and down like objects in a game of Whack-a-Mole over the years. Sometimes, forms of theatre have virtually disappeared. But theatre has always bounced back, to flourish — or struggle — on our stages today. Based on the past, I would argue that whatever difficulties the current climate is creating, the theatrical community will carry on in Vancouver. And that the Pacific Theatre, with its unique focus, supportive community, and strong leadership, is likely to be among the survivors.

James Hoffman’s account of historical theatrical performances in B.C. — first among indigenous peoples, then between indigenous people and visiting traders — seems to me an indication of the persistence and longevity of this form of art. The earliest recorded theatrical performances, used to establish relationships between indigenous peoples and visiting traders, “were staged with great ceremony on coastal waters in the closing decades of the eighteenth century,” he wrote, citing James Cook’s report of his first meeting with the local Nootka people “as they paddled their canoes towards the Resolution in Nootka Sound in 1778, [which] immediately positioned them as performers and his European crew as audience” (Hoffman, 2003, p. 3).

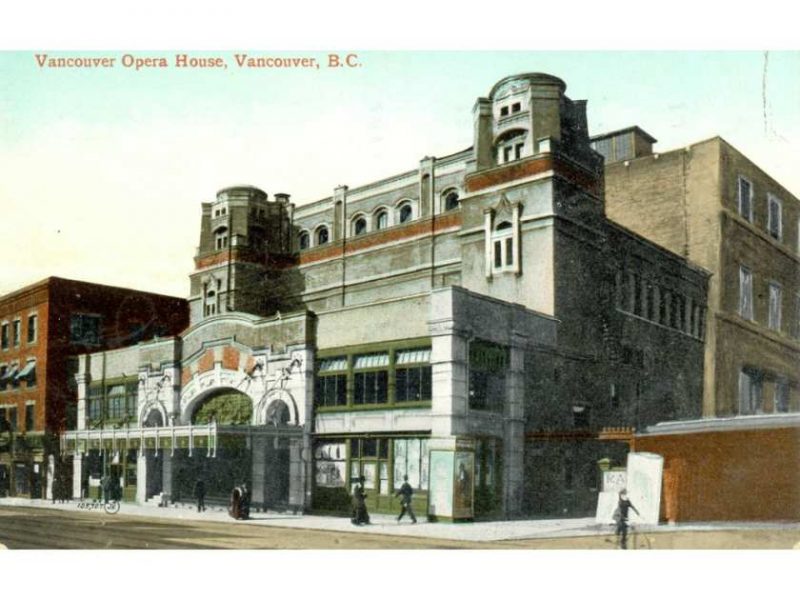

Vancouver’s own long list of past and present theatres, culminating in today’s bounty, is to me an indication of how hard it is to kill off this art form. But it’s always been a tenuous business. The city’s first major theatre, the Vancouver Opera House, had more staying power than most thanks to the deep pockets of its owner, the Canadian Pacific Railway Co., but even it only lasted a couple of decades. In 1895, four years after it opened, “there was a benefit performance to pay off the theatre’s debts, a sure sign of the economic woes of the day.” (Todd, 1979-80, p. 7). Things recovered after 1897 with the Klondike gold stampede but slowing economic growth in 1907 and 1908, and increasing competition from films and vaudeville, led to the sale of the Opera House by the CPR.

Renovated, it was reopened as the New Orpheum vaudeville house in 1913, the first of the city’s several Orpheums. Hoffman’s account of the rise and fall of The Everyman Theatre reiterates how external circumstances affect the theatre world. Theatres flourished in the booming 1920s, with “numerous resident stock and touring companies playing in nine legitimate houses,” then virtually disappeared in the 1930s, “leaving only the amateur and education groups with their non-commercial ideals,” due to the advent of radio, talking movies and the economic devastation of the Depression (Hoffman, 1987-88, p. 35).

Renovated, it was reopened as the New Orpheum vaudeville house in 1913, the first of the city’s several Orpheums. Hoffman’s account of the rise and fall of The Everyman Theatre reiterates how external circumstances affect the theatre world. Theatres flourished in the booming 1920s, with “numerous resident stock and touring companies playing in nine legitimate houses,” then virtually disappeared in the 1930s, “leaving only the amateur and education groups with their non-commercial ideals,” due to the advent of radio, talking movies and the economic devastation of the Depression (Hoffman, 1987-88, p. 35).

But there are no guarantees, even in the post-war boom of 1946, when Sydney Risk launched his ambitious effort to build a professional Canadian repertory company that would train and employ Canadian actors and bring affordable theatre to the people. The Everyman Theatre company lasted only seven years and struggled financially every step of the way. While the company’s work was considered a success and it was one of eight drama groups to play at the Dominion Drama Festival finals in Calgary in 1950, Risk and his father lost money, actors were chronically underpaid and at one point, a troupe member had to sell her typewriter to raise the $200 for train tickets so a tour could continue.

The lack of government funding (the Canada Council for the Arts didn’t exist until 1957) and the company’s idealistic bent may have been at least partly responsible, along with the fact that it didn’t have a theatre until its fourth season. When that hard-won location, a second-storey former dance hall over a grocery store on Main Street, vanished because of demolition, it was the move to a new theatre that helped kill The Everyman, according to Hoffman’s account. Risk had made financial arrangements with the owners of a new theatre that changed the whole co-operative tone of his company and led to his loss of control. He bowed out at the end of the 1952-53 season, taking The Everyman name with him.

I see echoes of The Everyman in today’s Pacific Theatre — the idealism, the difficult beginnings, the excellence of productions — but where The Everyman foundered in less than a decade, the Pacific Theatre has already survived for three. Published interviews with founding artistic director Ron Reed and my own interview with current marketing director Andrea Loewen reveal some of the reasons the theatre has survived so far, and why I think it might continue to do so in spite of the imminent loss of its home.

One reason is that it has a clear direction. “Pacific Theatre exists to serve Christ in our community by creating excellent theatre with artistic, spiritual, relational, and financial integrity,” says the mission statement posted on its website. ( http://pacifictheatre.org/about) When Reed and three other actors founded the theatre in 1984, their goal was to “establish a non-propagandist professional theatre where they would be free to explore work having particular meaning to them as Christians,” the website says.

Reed, who acts and directs in the theatre as well as serving as its artistic director, makes a clear distinction between being a Christian himself and the kind of plays the theatre does. “I readily say I’m a Christian, but we don’t do Christian theatre,” he said in an interview with Jason Byassee for Duke University’s online Faith & Leadership magazine (Reed/Byassee, 2015). “We do plays that explore spiritual questions honestly from a Christian perspective.”

But being identified with Christianity is risky in a devotedly secular city and province, and the Pacific Theatre paid the price. “We received no cultural grant money from any level of government for well over 10 years,” Reed said in the interview with Byassee, the Butler Chair in Homiletics and Biblical Hermeneutics at the Vancouver School of Theology. Theatre critics ignored the Pacific Theatre; even some actors were reluctant to associate with it. “It was a decade before we were reviewed in local media devoted to theatre here,” Reed said.

In an interview, the Pacific Theatre’s Loewen said stories about failed grant applications are part of the theatre’s lore. There were “awkward conversations,” she said, when Reed would try to suss out the reasons for the rejections. Told it was due to some small point or another, he would make a big show of relief — and a point about discrimination on the basis of religion — by exclaiming: “Oh, I thought it might be because of our Christian connections!”

In an interview, the Pacific Theatre’s Loewen said stories about failed grant applications are part of the theatre’s lore. There were “awkward conversations,” she said, when Reed would try to suss out the reasons for the rejections. Told it was due to some small point or another, he would make a big show of relief — and a point about discrimination on the basis of religion — by exclaiming: “Oh, I thought it might be because of our Christian connections!”

All that changed in 1994, when the theatre accepted an invitation from the Holy Trinity Anglican Church, owner of the historical Chalmers Heritage Building at 12th and Hemlock, to occupy its basement theatre. The grants came, the critics came, the Jessie awards came, and Reed told Byassee the theatre is “unarguably” part of the theatre community now. “Any barriers are ancient history.”

All that changed in 1994, when the theatre accepted an invitation from the Holy Trinity Anglican Church, owner of the historical Chalmers Heritage Building at 12th and Hemlock, to occupy its basement theatre. The grants came, the critics came, the Jessie awards came, and Reed told Byassee the theatre is “unarguably” part of the theatre community now. “Any barriers are ancient history.”

But Loewen said the theatre is still feeling the financial impact of the delayed government funding. Because it took so long to begin, the theatre gets proportionally less than many of its counterparts. Government funding usually goes up a small amount every year, she said, so some companies that have been getting it for many years now receive substantial amounts. Government grants, which come from four main sources — the Canada Council, the B.C. Arts Council, BC Gaming, and the City of Vancouver — are crucial for professional theatre, which is very expensive to produce, Loewen said. At costs of $35,000 to $75,000 per play, depending on the size of cast, the set and other particulars, “any company producing professional theatre has to get government money.”

But Loewen said the theatre is still feeling the financial impact of the delayed government funding. Because it took so long to begin, the theatre gets proportionally less than many of its counterparts. Government funding usually goes up a small amount every year, she said, so some companies that have been getting it for many years now receive substantial amounts. Government grants, which come from four main sources — the Canada Council, the B.C. Arts Council, BC Gaming, and the City of Vancouver — are crucial for professional theatre, which is very expensive to produce, Loewen said. At costs of $35,000 to $75,000 per play, depending on the size of cast, the set and other particulars, “any company producing professional theatre has to get government money.”

The Pacific Theatre, which has an annual budget of about $600,000, gets about one-third from the government, one-third from ticket sales and one-third from donors. Loewen said that by contrast, most companies get 40 or 50 per cent from grants, one-third from ticket sales and the rest from donors. “We depend more on individual donors than most companies,” said Loewen, noting that the theatre is a charity so people get tax receipts. “We do have a base of very loyal supporters that other theatres may not. The faith community is very supportive, and they’re also the type of people who are used to donating to charity.”

The Pacific Theatre, which has an annual budget of about $600,000, gets about one-third from the government, one-third from ticket sales and one-third from donors. Loewen said that by contrast, most companies get 40 or 50 per cent from grants, one-third from ticket sales and the rest from donors. “We depend more on individual donors than most companies,” said Loewen, noting that the theatre is a charity so people get tax receipts. “We do have a base of very loyal supporters that other theatres may not. The faith community is very supportive, and they’re also the type of people who are used to donating to charity.”

About 200 donors contribute anywhere from $10 to $100 per month, and others give $50 to $100 in the theatre’s twice-yearly major campaigns, she said. And then there are the lifesavers — a handful of big donors who can be depended on in emergencies, like a major equipment failure. Loewen noted that donors stepped in to fill the gap when the first three shows of the 2016-17 season — new plays by local artists — didn’t sell well. “The audiences were really low, so ticket sales were down and we didn’t get the usual number of seasonal subscriptions that we do at the start of the season,” she said. The lesson, she added, “is not to not stage these shows, but to schedule them differently.”

But the Pacific Theatre’s rough beginning also shaped it in a way that will likely ensure its future survival. “We’re very guerrilla,” Reed told Byassee. “We’ve stayed small. We can fight in any terrain, and we’ve transformed the way we do things many times to survive. We’re an edgy little theatre company.”

The hard times also solidified one of Pacific Theatre’s biggest assets – its strong base of supporters, whom Reed credits with keeping the company alive through its first difficult decade. “The level of support we get from our audience outstrips any other theatre,” Reed said. “That support grew slowly and made us part of the community. We did have three years when we were non-functional and had to cancel seasons, [but] our levels of donations didn’t go down.” Reed recalled how that support was there from the very beginning: Two of the four founding members didn’t have spouses who were working, so their church, Capilano Christian Community, found them a place to live for free.

The Pacific Theatre is also strong because it not only receives support from the community, but it supports the community in turn. Its website describes it as a “community-minded professional theatre,” that offers an extensive apprenticeship program, fosters both new and established work, supports emerging and established artists, and “engages the community at large.” Loewen said a number of theatre professionals have emerged from the apprenticeship program; she’s one herself. The company’s work in the community also included five years of touring with The Dragon’s Project, putting on plays mainly for young audiences, encouraging students to avoid substance abuse and urging the addicted to seek treatment.

Although the Pacific Theatre has a definite focus — to “rigorously explore the spiritual aspects of human experience” — its audience goes beyond the Christian community. Which is a plus in a province that has the fewest Christians on average of any province or territory, according to a 2013 Vancouver Sun story (Todd, 2013). “Folks have found that they like what’s on the stage,” Reed told Byassee. “Many call themselves Christian — not the majority at this point. All I know is we’re digging into things that matter.”

If the Pacific Theatre’s 2016-17 season is an example, I would argue that it offers enough diversity and variety to continue to appeal to theatre-goers regardless of its future location. Among its offerings: a play about a mechanic involved in a biker gang (Cara Norrish’s A Good Way Out); a Mafia tale based on what would have happened if Shakespeare had written The Godfather (Corleone: The Shakespearean Godfather, by David Mann); a comedic re-imagining of the nativity (Lucia Frangione’s Holy Mo! A Christmas Show!); a South African story about a poor worker’s granddaughter dreaming of becoming an actress (Valley Song, by Athol Fugard); an immigrant’s description of moving to Canada from South Korea (Maki Yi’s Suitcase Stories), and season-ender Outside Mullingar, by John Patrick Shanley, which I saw.

A romantic comedy set in the Irish countryside, Outside Mullingar was a tightly professional play full of Irish humour delivered with finely honed accents. That play contained such a brief reference to religion — a character has a revelation while working in the fields — that an inattentive audience member could miss it. But there is no effort to avoid religious topics: Next season begins with The Christians, an off-Broadway production that features a pastor who splits his church when he announces there is no hell.

A romantic comedy set in the Irish countryside, Outside Mullingar was a tightly professional play full of Irish humour delivered with finely honed accents. That play contained such a brief reference to religion — a character has a revelation while working in the fields — that an inattentive audience member could miss it. But there is no effort to avoid religious topics: Next season begins with The Christians, an off-Broadway production that features a pastor who splits his church when he announces there is no hell.

For all the emotional wrench that it will be to leave Holy Trinity Anglican, with its peeling-paint white dome that makes it a south Granville landmark, Loewen said the Pacific Theatre had been looking to relocate even before the redevelopment was announced. The company was hoping for a space with a few more seats to give it room for growth “and to improve our street presence and back of house.”

And although the theatre had a good deal with the church financially, the dressing rooms and back of house are “moderate to not-great” and below-height tunnels that serve as exits and entrances for actors “aren’t great for obvious reasons.” The greenroom gets tight when the cast is big, and there are no bathrooms connected to the dressing rooms, which she said can be awkward. “We were planning to engage in a slow process where we chip away at it and wait for the right opportunity, but instead now have an external timeline.” But the change will be difficult: “We are so tied to this space in terms of our identity, history, and memories, [that] the reality of having to leave, and before we were necessarily ready, was an emotional blow,” she said. “In many ways, it feels like moving out of your childhood home — there is a lot of potential to come, but it still feels like quite a loss.”

Its first leap into considering a new space was as a co-tenant in the BMO Theatre at the base of two condo towers, the result of an in-kind community amenity contribution from the condo’s developer, Wall Financial Corporation. “But the costs were not feasible for us,” said Loewen. In a paper about the city’s community amenity contribution scheme as it affects the arts, Simon Fraser University’s Peter Dickinson pointed out the heavy financial burden that sometimes come with such spaces. In the case of the West 1st facility, he estimated that while the Wall contribution was valued at $7.6 million, it would cost the arts groups and the city $12.8 million in capital financing to make it ready for use.

Dickinson wrote that the Arts Club and Bard on the Beach, the two tenants who took on the space, are big, successful organizations with good fundraising opportunities and plenty of donors, but they only took it because the city kicked in $7 million toward their operating costs. Faced with dollar signs like those, little non-profits like the Pacific Theatre don’t have a chance of getting into such facilities. “Who pays to keep the lights on in these spaces?” Dickenson asked (Dickinson, 2016, p. 41).

Loewen said that as of 2018, Pacific Theatre will be renting provisional space on Granville Island for two whole seasons, rather than having to look for space for each show as some smaller companies do. It’s heading to Studio 1398, described on its website as a third-floor “intimate black box theatre space” that can be configured to seat 111 people. (http://www.giculturalsociety.org/studio1398/)

“We’ll be able to make it resemble the theatre our audiences are used to, and hopefully they won’t mind too much,” said Loewen. “The main risks are that we will lose some audience in the move — some because they only came because of the convenience of our venue or who will see the new venue as a ‘step down.’ Others might just find it confusing and give up. It is also a risk because our costs will be higher with less freedom in our programming, so there is less opportunity to bounce back.”

Pacific Theatre’s current lease payments to Holy Trinity are about $50,000 annually, which includes office space and rehearsal space in the theatre. By comparison, Loewen said the Granville Island space rental will be about $70,000, but this isn’t definite because there will be additional costs for services like technicians. “Plus, we’ll need to rent office space. So the costs will go up significantly, with less freedom to program.”

There is some chance that Pacific Theatre may be able to return to the church after the renovations, but in the meantime, it will continue looking for other permanent space. Its primary focus will be on Granville Island, because space is opening up there with the departure of Emily Carr University, but even if it finds a permanent new home there, it will probably be more expensive than its current arrangement, said Loewen. “Because even if we get a cheaper lease, we will have to pay more for utilities, janitorial and property taxes than we do now.”

But theatres are about more than space, and the high costs of living in Vancouver are having an impact on everyone in the notoriously poorly paid theatre industry. A comparison of theatre salaries and current apartment prices provides a hint of the problem. Under the latest Actors’ Equity agreement, which sets out pay for theatre workers depending on the size of the company, Loewen said the Pacific Theatre will be paying equity actors $737 a week, while non-equity actors will make $550 to $600. Given the company’s commitment to emerging artists, the split is about 50/50 between equity and non-equity, she said. Directors will get $1,200 a week because of extra work performed before their contract actually starts.

Meanwhile, The Vancouver Sun reported that the apartment-hunting website PadMapper.com shows the median average June 2017 rental price of a one-bedroom apartment in Vancouver is $1,950; for a two-bedroom it’s $3,150 (Brown, 2017). If actors earning $737 a week were able to take home their full $2,948 a month, they’d have $998 left to live on after paying for an average one-bedroom apartment. Those at the low end of the pay scale, earning $2,200 a month, would have to survive on $250. Both groups would be in the hole if they rented a two-bedroom apartment.

Under these circumstances, how are theatre artists surviving in Vancouver? By working in the thriving TV and movie industry, which “helps keep many performers, designers and some directors living and working here,” said Wasserman, adding that “theatre is the expensive habit TV and film work allows them to indulge.”

Dickinson continued that besides the film industry, Vancouver also has a lot of video game production and voiceover work. “If you’re good and you get an agent, you can make a living working around the parameters of acting and performance.” But like Loewen, he said theatres are being affected because workers are being drawn off to better-paying gigs. Dickinson said the casting of his recently staged play Long Division “became a conversation about who was available because a number of people were off doing film production — a few weeks of which will pay for 20 or more weeks of theatre work.”

Loewen adds that conflicts sometimes arise between actors who do film work but want to work in the theatre as well, and their agents, who don’t want them to sign up for a month of low-paid work on a play when they could be working in films for more. She’s noticing people with transferable skills, like set designers, are less available for theatre, which causes frustration for directors.

Last year, the theatre lost three designers to better-paying gigs, two of those in film, she said. As a result, the company had to hire an inexperienced set designer for a complicated play. While it turned out well, she said, it was more stressful and difficult than if an experienced person had been available, and it forced others to carry a bigger load.

Both Loewen and Dickinson said in interviews that affordability and the question of whether to leave Vancouver is top of mind for many of the theatre people they know, with people constantly worrying about renovictions and finding affordable spaces to live. Loewen said she thinks sometimes about what amazing creations could have been produced if artists put all their “shall I leave or shall I stay?” energy into their work instead. “Everybody seems to be in agony over it,” she said. “It’s a very common topic.” More and more, she said, artists are taking time to juggle the math before committing to a project. Some opt out because of the low pay, to take on other kinds of work. Some take on everything they’re offered, overwork, and don’t do a good job anywhere because they’re so burned out. “More people are having to make these calls, and they’re talking about their frustration.”

Loewen said a small percentage of her friends in the theatre, including former Pacific Theatre colleague Frank Nickel have actually left, but a “huge percentage” are considering doing so. Nickel, the theatre’s former co-general manager, moved to Rosebud, Alberta — population under 100 — to become executive director of the Rosebud Centre of the Arts. Loewen said the tiny town exists for its theatre school and professional theatre, which draw from the surrounding area. She said Nickel had lived in Richmond, but when he and his wife decided to have a family, they realized they couldn’t survive there on his theatre income. Rosebud beckoned with better pay, a lower cost of living and an affordable house, and the family moved this spring. “Putting the life you want to have against the city you want to live in, you have to make a choice,” said Loewen.

Loewen and Dickinson worry that the theatre community might lose a whole cohort, people who have worked hard and established themselves but are now ready for the next stage of their lives. Loewen said people in that age group might not have cared – once — about living six to an apartment so they could carry out their dreams. But as they move into their 30s and start wanting to have families and settle down, they’re thinking differently.

That is theatre artist Emelia Symington Fedy’s story exactly. In a May 17, 2017 article in the Georgia Straight, she described how she hustled in her early years, taking any roles and supporting herself with restaurant work. After 15 years of intense effort, she was gaining some recognition “for creation-based work that toured nationally and internationally, yet monetarily it was still very tight. I lived in co-op housing. I didn’t eat out or drink or take days off, but it was still worth it. I was doing what I loved for a living, and that’s something you can’t put a price on. Right?” (Symington Fedy, 2017).

At 40, having officially made it, she got married and had kids – but now she feels the sacrifices for living in Vancouver are no longer worth it. It’s too much, she wrote, to be paying $2,500 a month for daycare while she works all day and into the night and her family is at risk of being renovicted at any time. She said she doesn’t have big aspirations — to own a house, go out for dinner, to buy new clothes: “All I want is my kids to have a back yard. And for that, I have to move across the country and begin again.” Vancouver, she said, is beginning to feel like an abusive partner. “You’re treating me like shit and I’ve given you everything I’ve got and I’m tired and I think you might be losing your heart.”

Which leaves Loewen and Dickinson wondering about the impact of a whole group of people like Symington Fedy simply bowing out of Vancouver. Loewen said this group has a decade of experience, and if enough leave, opportunities start to dry up. The work doesn’t advance and grow if everyone is a newbie, she said — it’s important to art that there is a good mix of young people who are experimenting and experienced older ones who can mentor and work with them. Asked if this could mean the loss of experimental theatre in Vancouver, she said, “I don’t think we’ll entirely lose the innovative part, but the balance may shift.” Anecdotally, she said, she thinks “even the Arts Club seems to be staging more audience-pleasers” — musicals, Jane Austen pieces — these days. “They are still doing some new local works, but there has been an increase in the amount of blockbuster works.”

Symington Fedy herself raised the issue of what happens to a city that loses people like her, who have contributed to the arts community for two decades — creating networks and shows based on her age group and its experiences. “I’m taking my art, my community service, my collaborations with kids, teens, students, and artists to Halifax” — the only urban centre with an arts community where her family can get a mortgage on a starter home in Canada. “Do you want this, Vancouver?” she asked in her article. “Do you want to lose the only thing that makes a city a home — its creative spirit?”

Wasserman said he found Symington Fedy’s article “very depressing but not unfamiliar or surprising.” As an actor who also had a regular full-time job, he always marvelled at colleagues who survived from gig to gig with no financial safety net, he said. Those who succeeded did so “through a combination of talent, hard work, resourcefulness and good luck,” and it’s much harder when children are involved. “But theatre people have been struggling with these issues forever. Obviously, the more expensive the cost of living, the more difficult it is to sustain a career where salaries rarely go up, and support a family. So it’s bound to have some impact on the arts scene here over the next few years, but it’s only different by degree, not by kind, from the norm that theatre artists face.”

Dickinson said the arts scene in any city depends on the emerging generation, and that is being interrupted by the cost of living in Vancouver. Those born in the 1990s, when prices started to ramp up, were dropped into a situation that previous generations didn’t have to deal with, he said. That increased the gap between established companies and artists and the newer, younger ones. “I think when we have such a huge gap between what a younger generation can afford in terms of just basic living that there is going to be a choice at a certain point where a number of artists are going to say, do they leave the city to practise somewhere else or do they leave the whole idea of making art by the wayside in order to get a job that just pays the rent?”

Some people in the dance community, Dickinson continued, work four or five different jobs, creating demands that “necessarily affect what you can devote to making good-quality art…. People make sacrifices; I think people will always make sacrifices and there will always be a generation of folks that will tough it out, but I think it is an issue and we need to find solutions to that in order to ensure that the people who are here don’t leave.”

Dickinson said he doesn’t think the number of theatre companies is any true measure of the vitality of the city’s theatre scene, because a certain number are always being created new while others die off. A better measure is the quality of the work. “I think on that level, Vancouver holds its own, in terms of producing adventurous work, in terms of producing issues-based work, in producing experimental work, we certainly have that range.” But he said all kinds of other things, like funding, space, and keeping tickets affordable, are needed to ensure the overall vitality of the theatre scene.

Another effect of Vancouver’s high prices is geographical, he said. Higher rents are pushing people to the edges of the city or out altogether, with a number of consequences. “Part of the ecology of having a strong community is having people actually in the community, present, and there’s a lot of people who are moving to New Westminster because it’s cheaper.” He recalled the split between the high-art mecca of Manhattan and the experimental art of Brooklyn when artists started moving to Brooklyn from Manhattan.

If all the young hungry artists were to move to outlying areas, the result would be a “vacuum” in Vancouver, which he predicted would be left with only big companies like the Arts Club presenting mostly commercial work. “I’m not saying we’re anywhere near that happening, but it’s a potential. We might need to make it affordable for people to rent spaces here.” Another aspect of geography is the simple difficulty of getting around the Lower Mainland, with its slow transit and clogged roads. Dickinson, who does not drive, said he often skips “amazing shows” at places like the Shadbolt Centre in Burnaby because he’d spend longer on transit than at the show itself.

I don’t think anyone can predict how the economic forces roiling Vancouver today will play out in the theatre world. How many in the industry will follow Symington Fedy and Nickel to cheaper places in Canada? Will struggling actors and their experimental works be pushed out of the city, leaving only bigger, richer, more commercial theatres in Vancouver proper? Wasserman said theatre thrives in expensive cities like New York, London and Paris — “cosmopolitanism is the lifeblood of professional theatre” — and companies and individuals cope by being “resourceful and resilient, and keeping costs down.” It’s no accident, he said, “that the most successful company in the city — the Arts Club — has been run for 40 years by an artistic managing director legendary for his frugality.” But Dickinson emphasized in a Simon Fraser University lecture in May 2017 that the arts scene is an ecology that needs fuel; without the arrival of a constant stream of new young artists, it “will disappear in this city.”

As I pondered their arguments, I couldn’t help but think of two numbers: The $1,950 rent for an apartment and the $2,200 paycheque for a non-equity actor. To me, they seemed like a metaphor for the ever-widening gap between the rich and poor we see around us every day in Vancouver; the multimillion-dollar mansions on one hand, the doorway mattresses on the other. Once again, as has happened throughout its history, the theatre scene is feeling the impact of the outside world.

I would argue that the Pacific Theatre, the “very guerrilla” operation that can fight in any terrain, will survive even the onslaught of condos. Wasserman, too, gives it a “pretty decent” chance, for many of the reasons I have already outlined. “They do very good work, have a very smart artistic director, and have developed a very loyal audience,” he said. “Plus they’re good Christians, so they have their faith to help keep them afloat. I’m confident they’ll be around long after those condos are built and occupied.” On this point at least, Wasserman and I agree. What will happen to the broader theatre scene remains an open question.

*

References

Brown, S. (2017, June 16). Average Vancouver rental price for 1-bedroom apartment is $1,950, according to PadMapper. The Vancouver Sun. Retrieved from http://vancouversun.com

Dickinson, P. (2017, June 2). Telephone interview.

Dickinson, P. (2016, Summer). Vancouverism and its cultural amenities: The view from here. Canadian Cultural Review, 167, 40-47.

Dickinson, P. (2017, May 2). On Long Division and Vancouver as an arts city. Lecture to GLS class.

Hoffman, J. (2003, Spring). Shedding the colonial past: Rethinking British Columbia theatre. BC Studies, 137, 5-45.

Hoffman, J. (1987-88, Winter). Sydney Risk and the Everyman Theatre. BC Studies 76: 33-57.

Loewen, A. (2017, May 29). Telephone interview.

Loewen, A. (2017, May 29, June 15). Email interviews.

Reed, R. (2015, Oct. 6). Ron Reed: I’m a Christian, but I don’t do Christian theater/Interviewer: J. Byassee. Faith & Leadership online publication for Duke University. Retrieved from https://www.faithandleadership.com

Symington Fedy, E. (2017, May 18-25). A goodbye to Vancouver. The Georgia Straight. p. 21

Todd, D., (2013, May 8). B.C. breaks records when it comes to religion and the lack thereof. The Vancouver Sun. Retrieved from http://vancouversun.com

Todd, R. (1979, December). The Organization of Professional Theatre in Vancouver, 1886-1914. BC Studies, 44, 3-20.

Wasserman, J. (2017, Feb. 20). Vancouver’s Arts Club Theatre ‘heart’ Bill Millerd to step down as artistic managing director. The Vancouver Sun. Retrieved from http://vancouversun.com

Wasserman, J. (2017, May 10). Vancouver Theatre and Theatre Criticism, Then

and Now. Open lecture.

Wasserman, J. (2017, June 18). Email interview.

*

Carol Volkart worked as a news reporter and editor with The Vancouver Sun for nearly four decades. After leaving the paper in 2013, she did some book editing, launched a blog (mountdunbar.blogspot.ca), and began work on a master’s degree in the Graduate Liberal Studies program at Simon Fraser University. This essay was written for the Arts, Criticism, and the City Shadbolt Seminar, a spring 2017 course examining the role of the arts and the state of arts criticism in Vancouver.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Comments are closed.