#140 Joy Kogawa’s reflections

First published June 17, 2017

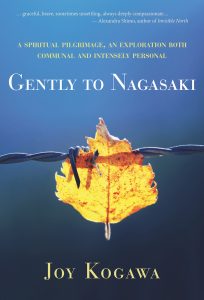

REVIEW: Gently to Nagasaki: A Spiritual Pilgrimage, an Exploration Both Communal and Intensely Personal

By Joy Kogawa

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2016.

$24.95

978-1-987915-15-0

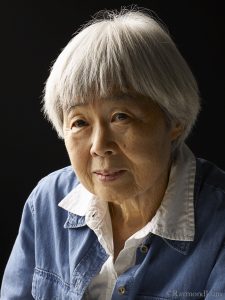

Reviewed by Patricia E. Roy

The librarian who provided the Cataloguing in Publication information gave Joy Kogawa’s Gently to Nagasaki a call number in the 800s in Dewey Decimal system. That would shelve it with literature.

Given Kogawa’s fine reputation as a writer of fiction and as a poet, this is an understandable choice especially since some of the prose reads like poetry and a number of comments explain how Kogawa created the characters in her much-praised novel, Obasan (1981), her subsequent reflections on its messages, and the origins of her novel, The Rain Ascends (1995).

This book, however, is much more than a literary exegesis. Many other call numbers are plausible. A case could be made for putting it in the 100s for it deals with the psychological effects of having a paedophile as a father. It could sit in the 200s beside other books about religion for the book has Biblical allusions, references to Christian feast days, and a discussion of issues within the Anglican Church in which Kogawa’s father was an ordained minister.

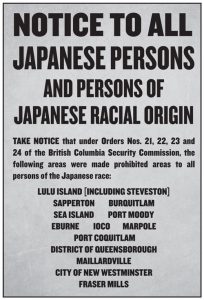

Another possibility would be the 300s since there is much about the Japanese Canadians, particularly during the time of their forced removal from the coast in 1942, the loss of their property, and the aftermath.

As Kogawa expresses it, “We were tossed as pearls in a broken necklace and as scraps for the dogs of labour, a few here, a few there, over the vast Canadian landscape” (p. 12).

One could even consider putting the book in the 500 or 600s, where its discussions of atomic energy could be related to medicine or technology.

Had I been the cataloguer, I would have assigned 921 to it, the number for autobiography for, though episodic and incomplete, this is very much a memoir. The subtitle accurately describes the subject and theme. Running through the book, beginning with the prelude, is the theme of Mercy.

Why Nagasaki? Nagasaki was the second Japanese city to suffer from the Atomic bomb. Ironically, as Kogawa emphasizes, it was “the pre-eminent spot of Christendom in East Asia” (p. 16), yet Christians dropped the bomb. “Somewhere in Nagasaki in August [1945], is God seeking mercy from us” (p. 30).

While she had no direct connection with the city until a visit in 2010, earlier she had been impressed by the story of Dr. Takashi Nagai, a Christian radiologist who, though injured and ailing, tended to victims of the bomb. As a scientist he carefully recorded the progress of radiation disease and the treatments applied, but still wrote that atomic energy could also be used for the betterment of humanity (p. 33). That leads to Kogawa’s debates with her friends, the anti-nuclear power sociologist Metta Spencer and the physicist Erich Voght who supported the peaceful use of nuclear energy.

The book then jumps back to Japan, to Kyoto. While there, accompanying her adored and elderly father who was on a speaking tour, Kogawa finally confronted him with what she had long known, that although “a visionary and charismatic priest,” he was a paedophile (p. 52). Telling him, and later telling the world through her writing, provided her with a release, a mercy. Nevertheless, even after his death she continued to wonder “how my blithe light-hearted father could be the epitome of evil” (p. 158).

Kogawa’s memoir also reveals tensions within the Japanese Canadian community as some would not forgive her father and opposed the turning of the family’s pre-war home in Vancouver’s Marpole district into an artists’ residence since it would also, indirectly, honour him.

Kogawa’s memoir also reveals tensions within the Japanese Canadian community as some would not forgive her father and opposed the turning of the family’s pre-war home in Vancouver’s Marpole district into an artists’ residence since it would also, indirectly, honour him.

Kogawa was not the only descendant to be troubled by the actions of an ancestor. Two granddaughters of Howard Green, one of the British Columbia Members of Parliament who called for the removal of the Japanese Canadians from the province, came to Kogawa when members of the Japanese Canadian community successfully campaigned against naming a new federal building in Vancouver after Green.

Kogawa was shocked to discover that her friend Stuart Philpott was the son of Elmore Philpott, a Vancouver journalist who, in 1942, also wanted the Japanese removed from the coast.

Despite the efforts of Green’s granddaughters to point out his many virtues, and of Philpott to explain the context of the time in which his father wrote, Kogawa could not extend mercy until the descendants admitted that their ancestors were racists.

Kogawa and her brother publicly admitted the “heinous sexual attacks” (p. 178) of their father, but the rage against him continued and Kogawa remained “the daughter of a paedophile” (p. 204). Yet, in a closing poem, Kogawa suggests the Goddess of Mercy listens.

Gently to Nagasaki is an intensely personal story and a tantalizing one. One hopes that Joy Kogawa will write a full autobiography that will clearly be catalogued as a “921.”

*

Patricia E. Roy, a native of British Columbia, is professor emeritus of History at the University of Victoria where she taught Canadian history for many years. Her own research has been mainly In the field of British Columbia history and she is best known for her trilogy of books on the responses to Chinese and Japanese immigrants: A White Man’s Province (1989); The Oriental Question (2003), and The Triumph of Citizenship (2007). All were published by UBC Press. She continues to publish articles in that field. Her most recent book is Boundless Optimism: Richard McBride’s British Columbia (2012), also published by UBC Press.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is hosted by Simon Fraser University.

The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

—

BC BookWorld

ABCBookWorld

BCBookLook

BC BookAwards

The Literary Map of B.C.

The Ormsby Review