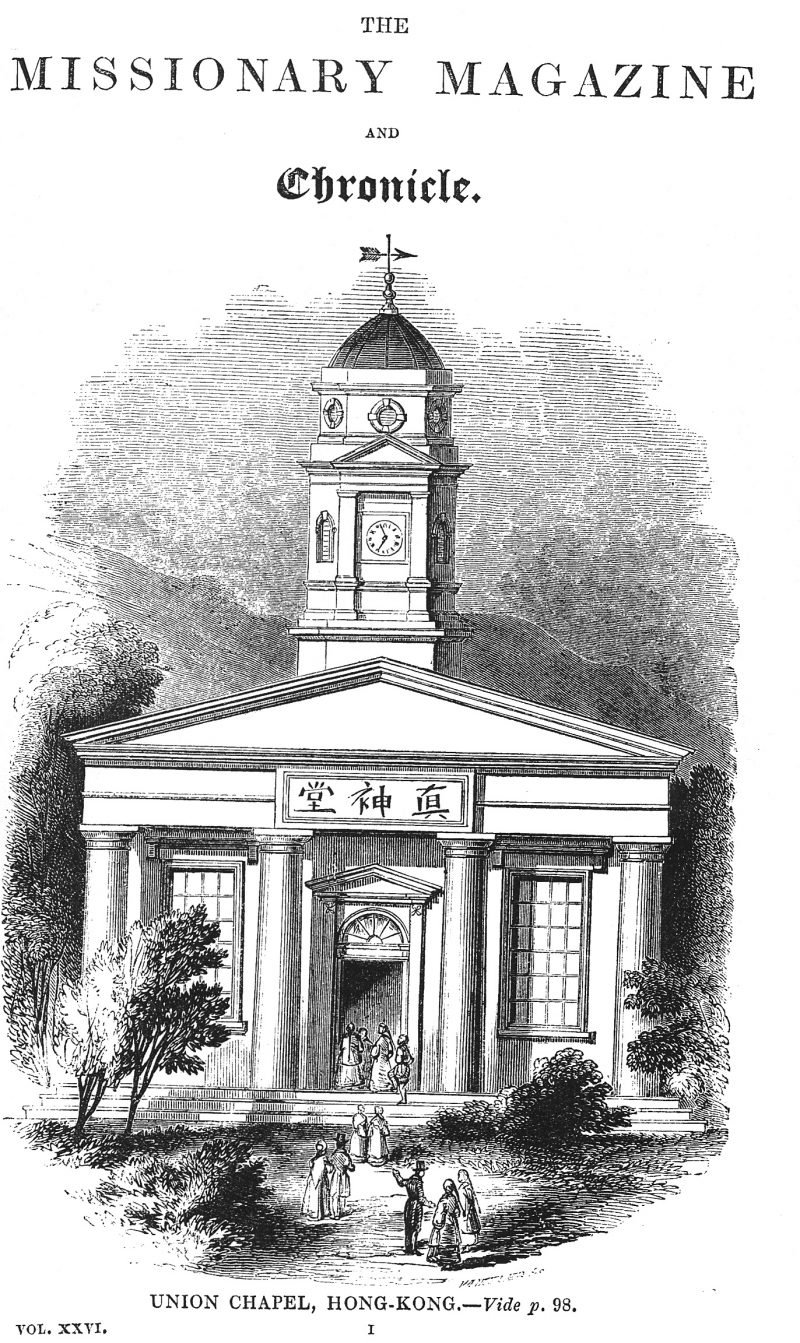

#134 Resuscitation of James Legge

James Legge and the Chinese Classics A Brilliant Scot in the Turmoil of Colonial Hong Kong

by Marilyn Laura Bowman

Victoria: FriesenPress Publishers, 2016

$37.99 / 9781460288832

Reviewed by Norman Girardot

First published June 2, 2017

Born in the Peace River country, Marilyn Bowman studied at the University of Alberta and McGill and taught Clinical Psychology at Queens University and Simon Fraser University, where she also held major administrative positions (Department Chair, Deputy Chair of Senate, Deputy Chairman of the Board) until her retirement in 2005.

Her encounter with James Legge — the Scottish missionary, sinologist, translator, and scholar (1815-1897) — combined her professional interests with an expertise in Asian history. Legge’s challenges in Hong Kong revealed his exceptional linguistic talents and steadfast psychological resilience at a time of great political and cultural conflict.

Bowman’s work on Legge, she writes, “has been great fun, not for a salary increase, not for an academic promotion, not for fame or wealth, but for the joy and enchantment of doing research on a terrifically interesting man in a very exceptional time and place.”

Reviewer Norman Girardot agrees. No one, he writes, “has presented so fully and effectively the broad human and cultural dynamic of Legge’s career in nineteenth century Hong Kong.” – Ed.

*

For almost one hundred years James Legge — the great nineteenth century Scottish missionary, translator of the Chinese Classics, active participant in the shaping of Hong Kong, and first professor of Chinese at Oxford University — had been mostly forgotten in the annals of formative pioneers in the intellectual and cultural history of the Western intercourse with, and understanding of, Chinese tradition.

There were many reasons for this neglect, not the least of which was the prevailing (and often justified) twentieth century secularist bias of a “hermeneutics of suspicion,” or “Orientalism” as it came to be called, regarding the motives of the British imperial agenda which was seen to distort the motives of the Protestant missionary movement.

In this sense, even Legge’s truly groundbreaking achievements as a translator and scholar of the Chinese Classics and the comparative study of Chinese religion were frequently trivialized, criticized as hopelessly one-sided, or simply ignored as an outdated example of a stilted and prejudiced Victorian scholarship. Indeed Marilyn Bowman ends her examination of Legge’s life and work with an Epilogue that interestingly reviews, and in many ways puts to rest, this unfortunate history of neglect.

However, Bowman’s book does not singlehandedly accomplish this resuscitation of Legge’s greatness and ongoing significance. In fact in the past twenty years there has been a boomlet of interest in Legge’s contributions to missionary history, Scottish intellectual tradition, the comparative history of religions, translation theory, British relations with China, and the overall checkered history of cross-cultural understanding. These developments are seen in a series of very substantial books, e.g., my own book (2002) and those of Lauren Pfister (2004), and M. K. Wong (2000), as well as numerous articles and conferences.[1]

With this much recent attention about Legge and his legacy, one may wonder what Bowman’s massive book (614 double-columned pages!) can add to our understanding. In this regard I am happy to report that Bowman, as an academic clinical psychologist with a special interest the human response to existential challenges and Asia, gives us a vastly expanded, meticulously researched, and insightful portrait of Legge’s personal and intellectual development – particularly with regard to his Scottish religious and intellectual heritage and his intimate involvement with colonial Hong Kong’s missionary, educational, cultural, and political history.

Pfister and Wong also deal with many aspects of Legge’s missionary activities in Hong Kong, but no one has presented so fully and effectively the broad human and cultural dynamic of Legge’s career in nineteenth century Hong Kong. My own work focused on Legge’s relationship with Max Müller and the emergence of an academic and “comparative” approach to the study of the so-called “Sacred Books of the East” and the “world religions.”

It is a fascinating and at times quite poignant story that Bowman has to tell, and despite what at first glance appears to be an egregious violation of Lytton Strachey’s dictum that biographers should sacrifice overly abundant detail in the interest of strategic selection and amusing anecdotal dramatization (see his Eminent Victorians, 1918; and I must admit that I am also a sinner in this regard), Bowman writes with a fluid accessibility, a talent for highlighting the entanglement of emotional and intellectual issues, and a merciful avoidance of academic jargon.

Yes, this is a very long book, but it has a momentum and engaging appeal enlivened by telling many evocative tales — whether instructive, comical, or simply sad — associated with colonial life, scholarly bickering, and missionary intrigue. Bowman has written a surprisingly sprightly narrative.

With regard to Hong Kong colonial history, I will only draw attention here to a few broad issues. It is worth noting that in addition to his identity and prominence at a missionary and scholar, Legge’s contributions to Hong Kong social, political, and religious life were amazingly multifaceted. This includes, for example and without trying to assign any special ranking, such accomplishments as his overall civic engagement and progressive social and cultural agenda; his reformation of missionary and public education; his role in the introduction of Western methods of mechanical printing and the use of movable metal type; his liberal attitude toward the establishment of an indigenous Chinese Christian church tradition that did not depend on the gross number of not-very-sincere “converts:” and his atypical public recognition of, and sincere respect, for his Chinese religious and scholarly assistants.

Also instructive are the descriptions of Legge’s life as a family man and the colonial social dynamics in the face of multiple calamities of fever, death, crime, fire, and poisoning; obstruction from the London Missionary Society (LMS); and nationalistic squabbling between British and Americans.

In many ways, Bowman’s account in the sections devoted to Malacca, Hong Kong, and the various trips back and forth to Scotland and England (chapters 16 through 49) gives us informative miniature histories of many different but interrelated and frequently controversial topics, issues, and people. Notable among these are matters relating to the history of, and struggle between, Britain and China and the evolving nature of missionary policy and scholarship such as the rancorous battles over a Chinese version of the Bible as related to the hotly contested “term question” about the translation of “God.”

Also noteworthy are her deft discussions of prominent Chinese such as the reforming scholar Wang Tao and pastor Ho Tsunshin; the complications of the Taiping rebellion and its syncretistic absorption of Christianity; and the eccentricities and duplicitous actions of various prominent missionaries (perhaps most notoriously, Charles Gutzlaff). To say the least, this is frequently quite colourful as well as periodically and sometimes simultaneously both optimistic and disturbing.

Amidst all of the riches of discerning historical description in the many pages devoted to Hong Kong, Bowman’s concluding sections about “Life, Beliefs, and Attitudes” (Parts 13 and 14) are also replete with many shrewd psychological reflections on Legge’s resilient character. Most of all, Legge was someone — throughout his life in Scotland, Hong Kong, and England — who displayed a great “psychological robustness” in the face of extreme personal and professional challenges.

Bowman’s analysis does not add much to theories about how and to what degree or combination “nature and nurture” contributed to a Legge’s psychological make-up. But more helpfully — if somewhat obviously after so much revealing personal detail — she concludes that Legge was fundamentally a “sanguine” person of very rare linguistic and scholarly abilities who was basically “genial, kind, helpful, and self-deprecating.” He could, however, be extremely “assertive” in contentious matters of missionary policy, civic mindedness, and scholarly debate. I will only say that, in keeping with my own assessment of Legge the man and scholar, Bowman’s analysis largely rings true. There was typically an intellectual assuredness on Legge’s part but never any real arrogance or religious righteousness.

In conclusion, it is worth noting the twenty-first century irony of Legge’s specific accomplishments with respect to his role as a missionary to China and his career in Hong Kong. Legge more than most missionaries of his era had strong misgivings about the cultural rigidity of Evangelical Protestant missionary policy and the failure to recognize the antiquity and greatness of the Chinese “classical” and “sacred” tradition. In this regard he also recognized the obvious fact that in the nineteenth century, Christianity had made little headway in terms of becoming an influential part of Chinese religious history. He always felt, however, that the careful laying of a culturally sensitive groundwork of understanding and respect would in due course lead to an authentic Chinese Christianity.

Legge would have wished this transformation to happen sooner rather than later, but he also knew that the foreign religious tradition of Buddhism took several centuries to be assimilated as one of the “traditional” religions of China.

What is so interesting is that it is only now in the twenty-first century that Legge’s hope for a Chinese Christianity is actually becoming a significant reality in the still officially atheistic Peoples Republic of China (see Ian Johnson’s The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao, Penguin 2017).

*

Norman Girardot is University Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Comparative Religions at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania. The recipient of numerous national and international fellowships, his research areas involve Chinese religious tradition, particularly Daoism; the intellectual history of the study of China/Chinese religions and the rise of the historical discipline known as “comparative religions;” the problems of cross-cultural understanding; and the relation of religion and outsider/vernacular/visionary art. His books on Daoism and on James Legge (The Victorian Translation of China: James Legge’s Oriental Pilgrimage, University of California, 2002) have won numerous awards and have appeared in Chinese translation. In 2009 through 2013 he initiated and was a primary investigator for a major Henry Luce Foundation grant that led to inter-collegiate, interdisciplinary, and cross-cultural student programs involving Chinese tradition.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors in all fields and genres. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] Norman Girardot, The Victorian Translation of China: James Legge’s Oriental Pilgrimage, University of California, 2002); Lauren Pfister, Striving for ‘The Whole Duty of Man’: James Legge (1815-1897) and the Scottish Protestant Encounter with China. Vol. 34 in the Scottish Studies International Series edited by Horst W. Drescher (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2004); M.K. Wong, British Missionaries’ Approaches to Modern China, 1807-1966 (Hong Kong: Hong Kong Baptist University, 2000).