#109 From exclusion to equality

Great Fortune Dream: The Struggles and Triumphs of Chinese Settlers in Canada, 1858-1966

by David Chuenyan Lai and Ding Guo

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2016

$26.95 / 9781987915037

Reviewed by Tzu-I Chung

First published March 27, 2107

*

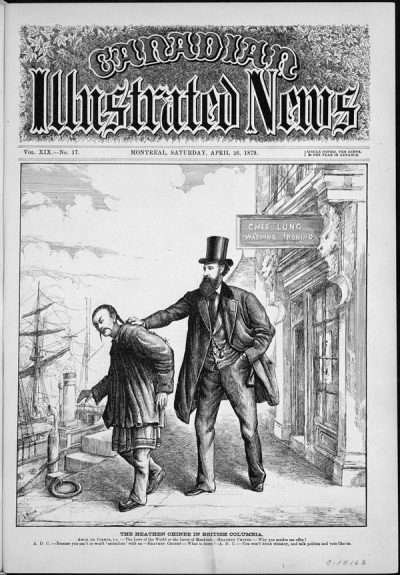

In Great Fortune Dream, David Chuenyan Lai and Ding Guo tell of the struggles and triumphs of Chinese settlers in Canada in the century after 1858 as they navigated immigration policies that ranged from free entry, to a head tax, outright exclusion, selective entry, and finally to the points system initiated in 1967.

In Great Fortune Dream, David Chuenyan Lai and Ding Guo tell of the struggles and triumphs of Chinese settlers in Canada in the century after 1858 as they navigated immigration policies that ranged from free entry, to a head tax, outright exclusion, selective entry, and finally to the points system initiated in 1967.

Reviewer Tzu-I Chung of the Royal B.C. Museum takes a close look and finds Great Fortune Dream “a welcome addition to the growing literature on Chinese Canadian history.” – Ed.

*

As a field of study and a topic of interest, Chinese Canadian History has received increasing scholarly and public attention in the past decades. Dr. David Chuenyan Lai and Ding Guo add to this field in Great Fortune Dream, a translated and abridged version of a book originally written for a Chinese readership and now adapted for a Canadian audience.

This interdisciplinary book focuses on Chinese Canadians’ pre-1967 challenges and contributions to Canada. It ends in 1966, a year before the Canadian government adopted the universal immigration policy, which applied a points system for selecting potential immigrants and effectively stopped the historical discrimination against Chinese migrants in the preceding “selective entry” era.

Great Fortune Dream’s major appeal lies in its integration of first-person or family narratives with historical accounts of Chinese Canadians’ responses to challenges of discrimination. Such narratives and accounts derive from both Chinese and English-language sources.

The book is divided into four chronological periods based on Canadian entry policy for persons from China: the free entry era of 1858-84, the head tax era of 1885-1922, the exclusion era of 1923-46, and the selective entry era of 1947-66. This structure highlights the impact of immigration policies on the Chinese in Canada.

Against this background of discrimination in government policy, the book reveals Chinese Canadians’ real life experiences, struggles, cultural practices, and most importantly their assertive roles as agents of change and contributors to the building of this nation.

Interestingly, Chinese Canadians’ active agency in the face of challenges is also supported by official Chinese and English-language accounts, such as four methods to “evade the expensive head tax” revealed by Royal Commissioner Justice Dennis Murphy (pp. 65-7) and the groundwork of resistance to the head tax provided by the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association and Chinese government.

In addition to its focus on the Chinese Canadian contribution to Canada, Great Fortune Dream also draws significantly on Chinese Canadians’ lesser-known contribution to the “transformation of China” (p. 138), a reminder of the importance of transnational connections in shaping Chinese Canadian lives.

Owing to the book’s original Chinese audience, the book contains some rare accounts of Chinese Canadians in China, such as the stories of the Overseas Chinese Volunteer Army in 1915 (p. 146). Such vignettes, with stories of real people, illustrate the unexpectedly far reach of Chinese Canadians.

Great Fortune Dream, with its emphasis on the narrative of Chinese Canadian challenges and contributions, combined with its accessible language, makes a nice complement and addition to From China to Canada: A History of the Chinese Communities in Canada by Edgar Wickberg, Harry Con, and others (McClelland & Stewart, 1982) — but Lai and Guo break new ground in section IX on the “selective entry” era of 1947-66, a period not covered by previous general histories.

Here, the authors describe the transitions and struggles that Chinese Canadians went through even after 1947, despite being granted voting rights and the lessening of other discriminatory measures.

As a general history, I must also note that Great Fortune Dream draws on Chinese Canadian lives in British Columbia more than in other parts of Canada, which is due in part to the longer development of Chinese Canadian communities in B.C. and the deep contribution of scholars such as Dr. Patricia Roy and Dr. Lai himself.

Future researchers on Chinese Canadian history would do well to work with existing community projects to find and popularize stories from different corners of regions and provinces in Canada and to address other nuances that inform the diversities of the intercultural relationships that shape Chinese Canadian communities.

The authors also acknowledge differences in social classes and political orientation within Chinese Canadian communities, and Great Fortune Dream provides some intriguing findings. For example, Chinese Canadians in B.C. gambled a million dollars in the 1910s (p. 126) – but I was left wondering what the source of this estimate is, and how it compared to gambling within non-Chinese communities of similar population and size.

The authors also mention that “many Chinese doctors” trained in western medicine were practicing in the 1920s (p. 188) – an exciting finding but on the face of it a puzzling one, given that most Chinese could not practice medicine in B.C. at the time.

This book would make a greater addition to the academic field if it came with supporting citations and notes. If another edition is contemplated, I hope the authors will provide some justification and clarification in the use of certain terminology. For instance, Lai and Guo state that in 1872, “The Chinese were prevented from voting, even though they were Canadian citizens” (p. 44). However, the status of “Canadian citizen” was not created until the Immigration Act of 1910. Prior to that, Canadians were classified as British subjects.

Despite these caveats, with its broad temporal sweep and interesting new details, Great Fortune Dream is a welcome addition to the growing literature on Chinese Canadian history.

*

Dr. Tzu-I Chung is a cultural and social historian, broadly interested in transnational migration between North America and the Asia-Pacific regions. Since becoming a Curator of History at the Royal B.C. Museum in 2011, Tzu-I’s research has focused on B.C.’s diverse cultures and communities and their transnational connections. Her work is enriched by her experience in community outreach and her own cross-cultural and multi-lingual background.

Dr. Tzu-I Chung is a cultural and social historian, broadly interested in transnational migration between North America and the Asia-Pacific regions. Since becoming a Curator of History at the Royal B.C. Museum in 2011, Tzu-I’s research has focused on B.C.’s diverse cultures and communities and their transnational connections. Her work is enriched by her experience in community outreach and her own cross-cultural and multi-lingual background.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

—

BC BookWorld

ABCBookWorld

BCBookLook

BC BookAwards

The Literary Map of B.C.

The Ormsby Review