#84 The coast was not clear

The Queen of the North Disaster: The Captain’s Story

by Colin Henthorne

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2016

$24.95 / 9781550177619

Reviewed by Jan Drent

First published Feb. 8, 2017

*

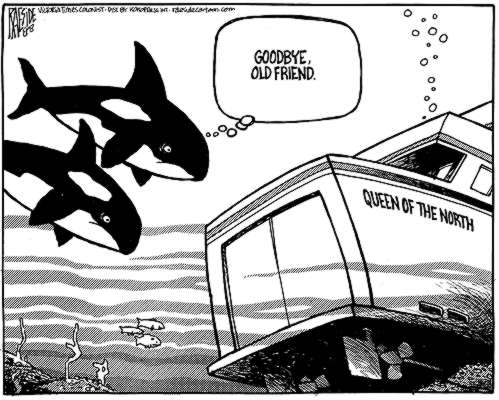

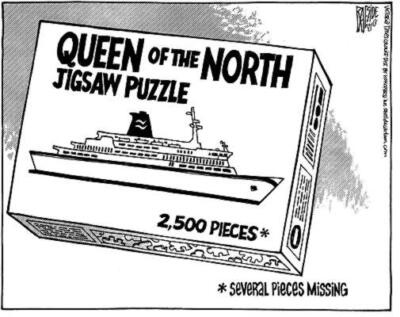

Ten years after the sinking of the Queen of the North in 2006, the vessel’s captain, Colin Henthorne, provides a first-hand account of why the ship struck an underwater ledge off Gil Island, 135 kilometres south of Prince Rupert.

The impact tore open the ship’s bottom, ripped out both propellers, and sent the ship to the bottom of Wright Sound with the loss of two lives.

Reviewer Jan Drent, who commanded destroyers in the Royal Canadian Navy and served as Canadian Naval Attaché in Moscow, Helsinki, and Warsaw, assesses the decisions made on the bridge of the Queen of the North on that fateful night on the Inside Passage –Ed.

*

At twenty minutes after midnight on Wednesday, March 22, 2006, the BC Ferry Queen of the North, well off her normal track, drove onto an underwater ledge at 17.5 knots (32.4 km/hour) on a remote stretch of the Inside Passage.

At twenty minutes after midnight on Wednesday, March 22, 2006, the BC Ferry Queen of the North, well off her normal track, drove onto an underwater ledge at 17.5 knots (32.4 km/hour) on a remote stretch of the Inside Passage.

The underwater hull was fatally damaged but momentum carried the vessel into deep water where she filled with water and sank eighty minutes later. The ship was being operated by a crew of forty-two on a routine run from Prince Rupert to Port Hardy.

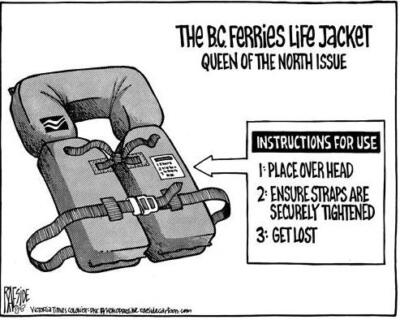

Fortunately, although her maximum passenger capacity was 650, there were only fifty-nine on board during this winter voyage. In favourable weather conditions there was sufficient time for an orderly evacuation of passengers and crew into lifeboats, life rafts, and a rescue boat carried by the ferry.

The captain, Colin Henthorne, was among the last to leave the ship thirty minutes after the grounding. Other vessels in the area and people at Hartley Bay, six miles away, had heard the ferry’s distress call and responded promptly. Help began arriving even before the Queen had sunk. Tragically, two passengers — Gerald Foisy and Shirley Rosette from 108 Mile House — had disappeared and were later declared dead after a prolonged RCMP investigation.

Queen of the North, just out of a $3.3 million refit, was a well-equipped modern vessel crewed by experienced mariners on a familiar voyage. How could this horrific accident with the loss of two lives have happened?

Colin Henthorne sets out his version of the sinking and its aftermath in The Queen of the North Disaster: The Captain’s Story. His story is complex. He writes clearly, explains issues unfamiliar to general readers, supports his narrative with welcome footnotes, and includes a comprehensive glossary of nautical terms. This book has been nicely produced by Harbour Publishing and contains a useful index.

The sinking became notorious almost immediately amidst intense public interest. It became known that the only crewmembers on the bridge, Fourth Mate Karl Lilgert and Quartermaster Karen Briker, had recently ended a relationship.

Rumours and speculation abounded because they and the Second Mate, Keven Hilton, who was the senior officer on watch, but who was on a meal break, all refused to explain to initial investigators and the media what had happened.

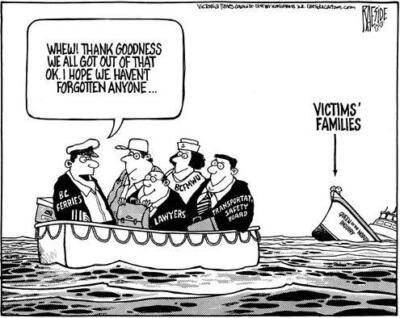

What followed were two official inquiries, other hearings, a coroner’s report, and finally a trial seven years after the event, which found Karl Lilgert criminally negligent in the deaths of the two passengers.

Captain Henthorne was one of five crewmembers whose employment was eventually terminated by BC Ferries. His book tenaciously disputes many of the findings in the official inquiries and the trial and challenges the termination of his captain’s position.

Henthorne and other crew members were questioned promptly by a BC Ferries team, which released a “Divisional Inquiry” in March 2007, one year after the sinking. Meanwhile, the federal Transportation Safety Board, which investigates the causes of accidents but does not recommend any disciplinary actions, had its own inquiry underway and sent the Sidney B.C.-tethered submersible ROPOS down 427m (1,400 feet) to the wreck to recover the hard drive from the electronic chart system.

The Transportation Safety Board inquiry was not released until March 2008, two years after the event. The Supreme Court of British Columbia had declared the two missing passengers presumed dead in April, 2007. The orphaned children of Gerald Foisy and Shirley Rosette sued BC Ferries for damages due to wrongful death; but without the cash required to take their cases to trial, they settled out of court in 2009. A coroner’s report on the death of Gerald Foisy was completed in September 2010 as part of the evidence required for the criminal trial.

Henthorne’s employment with BC Ferries was terminated by the company in January, 2007. The following year, he won a Workers’ Compensation Board appeal about his dismissal and was re-instated in May, 2009. He then worked three, two-week shifts as Master of the Queen of the North’s replacement ferry starting in November, 2009.

Meanwhile, BC Ferries had successfully appealed the original Workers’ Compensation Board decision, and Henthorne’s employment was terminated for a second time in March, 2010. His subsequent appeals of the WCB Tribunal decision, first to the Supreme Court and then to the Appeals Court of British Columbia, were unsuccessful. He has now painfully re-established his career as a Canadian Coast Guard Rescue Co-ordinator in Esquimalt.

The inquiries by BC Ferries and the Transportation Safety Board identified various issues requiring action by BC Ferries and Transport Canada. However, both found that the ship had been adequately equipped and crewed. BC Ferries had not provided an emergency evacuation plan for the ferry.

Henthorne reveals that, during the sinking, the crew used a cabin search system that he had designed and exercised during weekly fire drills. He reveals that some crew members had to escape from accommodation that was being flooded below the car deck, and that therefore some crew members earmarked for the search were not available. The search was also hampered because the chalk was missing that was supposed to be used to mark cabin doors as they were cleared of occupants. Later, because of conflicting head counts, it took a long time to establish definitely that two passengers were missing.

Both official inquiries determined that actions by the Fourth Mate caused the grounding. The Supreme Court ruled that he had failed to safely operate or navigate the Queen of the North, causing the death of two passengers.

Captain Henthorne explains that the ferry’s deck watches worked in two twelve-hour shifts. There were two certified Mates in the night shift, but only one was normally on the bridge except in restricted visibility or when transiting “the more challenging passages.”

Fourth Mate Lilgert took over conduct of the ship on the bridge from Second Mate Keven Hilton in good visibility shortly before midnight on March 21, 2006. The ferry was being steered by its autopilot system. Soon afterwards, she entered a broad stretch of the Inland Passage called Wright Sound. Mate Lilgert called Prince Rupert Marine Traffic to report that he would be altering course 17 degrees to port to take him clear of Gil Island, which jutted out into the Sound four miles ahead. However, the Queen of the North maintained course for fourteen minutes beyond the planned alteration without changing speed and eventually ran aground.

Henthorne does not say whether he and his officers had been alerted to unfavourable weather through weather forecasts or reports during the voyage. The Transportation Safety Board inquiry cited an Environment Canada analysis that the passage through a Cold Front had brought gale force southeasterly winds and heavy rain through the area.

The Queen therefore encountered heavy rain and high winds around the time she entered Wright Sound. The BC Ferries Divisional Inquiry established that, when Mate Lilgert took over the watch in the channel leading to the more open waters of Wright Sound, winds were already westerly at twenty knots. Lilgert told his trial that the ship encountered a squall that reduced visibility shortly before entering Wright Sound.

The post-accident investigations determined that a shrimp boat, which had been pointed out to the Mate on taking over conduct as being four miles ahead, moved north out of Wright Sound to shelter from the squall. Lilgert testified that he decided to delay his planned alteration of course because he was concerned about a contact ahead, which he had lost on radar.

Moments before striking the underwater ledge just off Gil Island, the Mate ordered his quartermaster to alter course to port. As she left her chair to make the change, both Lilgert and Quartermaster Briker apparently sighted trees off the starboard bow. The Mate ordered his quartermaster to switch to hand steering, but she told him that she did not know how to do so.

The Transportation Safety Board determined that the ferry’s course did in fact begin to alter to port shortly before striking the ledge. The impact sheared off both propellers and the Queen eventually drifted off to the northward. Meanwhile, Captain Henthorne had been summoned to the bridge, where he took charge.

Henthorne writes that he had long wondered what happened on the bridge and formed a theory only after the criminal trial, seven years after the accident. He firmly disposes of the rumours of salacious activity.

In his view, poor bridge layout and defective equipment contributed to the ship’s loss. During the recent refit, one of the two radars had been replaced and the system for switching between automated and manual steering had been modified. By the time the ferry was lost, Henthorne and his crew had accomplished three round voyages between Prince Rupert and Haida Gwai and one round trip to and from Port Hardy using the new systems. The Queen of the North’s other regular crew had previously operated the ship successfully for twelve days in the same waters.

The BC Ferries inquiry noted that no crew members had reported defects in bridge equipment. The high winds and heavy rain brought by the squall encountered in Wright Inlet would have caused clutter on radar displays.

Henthorne postulates that Mate Lilgert was so preoccupied in trying to find a target previously seen on radar through clutter that he lost situational awareness. He does not speculate on how long the squall lasted. When the ferry grounded, it was not raining and the evacuation of the ship was not hampered by winds.

Henthorne is particularly scathing about the new radar systems that had been installed in the recent refit, stating that he told the trial that they were “third rate” (p. 70). An electronic navigation system that displayed the ship’s position based on GPS input on an electronic chart was at the front of the bridge.

The Transportation Safety Board inquiry learned that Mate Lilgert had turned down the brightness on the electronic navigation system to avoid interference with night vision, and the inquiry learned that other bridge officers were in the habit of doing the same thing. As a result, Lilgert would have been unable to readily observe what the electronic navigation system was telling him about the ship’s position.

Yet Henthorne writes that the electronic navigation system was “almost unusable” because of “massive faults” (p. 100). One of the navigational techniques using radar is called parallel indexing. Henthorne provides a concise description backed by a clear diagram (p. 89), but in his opinion the ship’s equipment was so cumbersome that parallel indexing was “practically useless.”

He does not speculate on why the Mate, even if concentrating on trying to locate a target on radar through sea return, did not observe land echoes growing closer (“sea return” occurs when waves reflect a radar echo, hampering target identification).

In June, 2013, following a trial by a Supreme Court of British Columbia judge and jury, Mate Lilgert was found guilty of criminal negligence causing the death of the two passengers and sentenced to four years in prison. The relevant section of the Criminal Code specifies that everyone is criminally negligent who (a) in doing anything, or (b) in omitting to do anything that it is his duty to do, shows wanton or reckless disregard for the lives and safety of other persons.

The trial heard expert opinion that Karl Lilgert failed to reduce speed in restricted visibility, to keep a good lookout, to call the Second Officer or the Captain, or to call the standby deckhand as an additional lookout, as prescribed.

Henthorne concedes that all of these actions could have been appropriate, but he feels that the “real problem was with the Fourth Mate’s assessment of the situation. All evidence points to the fact that he did not perceive how close to the island he was” (p. 104). Henthorne rejects the notion that Lilgert was negligent.

While elsewhere stressing Mate Lilgert’s professional competence and experience, Henthorne writes that the issue was “proficiency not criminality” (p. 76), and he adamantly disputes the notion that the Mate was distracted by the presence of Quartermaster Briker.

Henthorne writes that “no one has been able to determine exactly why” Mate Lilgert failed “to determine his position or course made good over the last few minutes” before the grounding, “and this is the one essential thing that needs to be determined” (p. 99). He suggests that an equipment failure or difficulties in using the bridge systems might well explain the problem.

Elsewhere, Henthorne asserts that investigators failed to probe the “human factors” that led Lilgert, who he states had more than 10,000 hours of navigational experience, to make faulty decisions. Indeed, Henthorne is so determined to dispute the results reached by painstaking inquiries and a four-month trial that he offers judgements that are open to question. Thus he suggests that because “There are so many ways to go wrong navigating the confined waters of the Inside Passage, it is seldom necessary to posit gross dereliction of duty as an explanation for an accident. Slight miscalculation is often a fully adequate reason” (p. 76).

But what became a disastrous situation on the bridge unfolded in just under a quarter of an hour. Was not realizing that the ship was standing into danger really a “slight miscalculation”?

Colin Henthorne apparently has over thirty-four years of experience as a ship’s master. He also has an aircraft pilot’s licence. Readers of this book will learn a lot about crewing in BC Ferries and the impact of the traumatic sinking on passengers and crewmembers. And indeed, lessons were learned. Management and the unions instituted a new program called SailSafe — not cited here — to identify and deal with safety issues called.

BC Ferries now operate with two certified navigation watch-keepers plus a trained Quartermaster on the bridge at all times, but Henthorne is grudging about the effectiveness of the Bridge Resource Management training provided after the accident.

The Queen of the North Disaster, while written by a thoughtful and highly seasoned mariner, strains credulity about why this ship was lost, largely because the author is so one-sided in challenging what was determined by official inquiries, hearings, and a trial.

*

A graduate of UBC, Jan Drent was a career officer in the Royal Canadian Navy. He commanded He commanded two destroyers and a 22.000-ton replenishment ship on both coasts and served ashore in Canada and overseas. Since retiring to Victoria with his wife, Jan has been active as a volunteer. He has pursued interests in languages by doing freelance translations from Russian and German. His nautical writings have included articles and book reviews in periodicals in Canada and the UK. His hobbies include sailing, walking, and reading.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster