#70 Getting tipsy in Victoria

Aqua Vitae: A History of the Saloons and Hotel Bars of Victoria, 1851-1917

Glen A. Mofford

Victoria: TouchWood Editions, 2016

$19.95 / 9781771511896

Reviewed by Martin Segger

First published Jan. 10, 2017

*

For a community that has been known to present its history as a Edenesque garden-city on the fringes of the British Empire, Victoria exhibits a certain precosity when addressing matters of alcoholic beverage manufacture and consumption.

In recent times the City has boasted the first craft brew-pub (Spinnakers) and one of the first brew-pub hotels (Swans), also the densest urban concentrations of micro-breweries in North America. That not all these claims are verifiable matters not.

Since 1918 Victoria hosted the head office of the Provincial Liquor Control Board (originally the Prohibition Commission) with its own legacy of colourful chief commissioners. Typical of the many anecdotes recounted by Glen A. Mofford in Aqua Vitae, he notes Victoria’s first commissioner, W. C. Findlay, was also the first person to be convicted of bootlegging, then fined and jailed under the new Prohibition Act of 1918.

Since 1918 Victoria hosted the head office of the Provincial Liquor Control Board (originally the Prohibition Commission) with its own legacy of colourful chief commissioners. Typical of the many anecdotes recounted by Glen A. Mofford in Aqua Vitae, he notes Victoria’s first commissioner, W. C. Findlay, was also the first person to be convicted of bootlegging, then fined and jailed under the new Prohibition Act of 1918.

Aqua Vitae is both serious history and an entertaining arm-chair guide to the early drinking establishments of Victoria, their proprietors and patrons. The narrative framework is the regulatory history of alcoholic consumption in the City from the first granting of liquor licences by Governor James Douglas in 1860 to the end of the public saloon era with prohibition in 1918.

Prior to this the first hotel in Victoria, Bayley’s, located on the corner of Yates and Government streets in 1857, was accompanied by the establishment of a chapter of the American society, Sons of Temperance, foreshadowing things to come fifty years later.

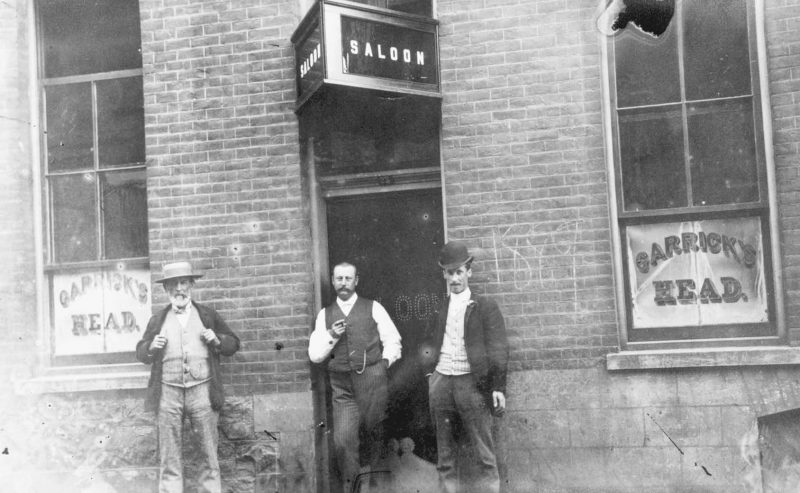

Five chapters, generally chronological, then trace the economic and social history of drink through portraits of 46 establishments that dotted the city landscape over those years.

Chapter 1 covers “Pioneer Hotel Bars 1851-59;” Chapter 2, “The Rough Edges of Town, 1860-69;” Chapter 3, “Strictly First-class;” Chapter 4, “The Golden Age, 1870-99;” Chapter 5, “Restrictions to Prohibition, 1900-17.” The conclusion is aptly titled “Bottom of the Glass.”

Along the way we meet shrewd entrepreneurs, colourful publicans, and raucous clientele along with corpses excavated from beneath barroom floor boards and midnight escapades to steal confederate flags. There are murders, injuries, suicides, litigations, bankruptcies but also acts of philanthropy and outstanding citizenship.

At the time of confederation in 1871 Victoria boasted 85 drinking establishments clustered in and around the city core. By 1909 there were a 109 such establishments, including several multi-room luxury hotels. These housed and serviced Victoria’s swelling and swilling visitor population. The Pacific Base at Esquimalt of the Royal Navy alone poured a $500,000 into the community. Sealing and whaling fleet crews also over-wintered in the hotels and rooming houses that clustered around Rock Bay. Waves of gold seekers, adventurers, and remittance men came and went along with saloons such as the Boomerang, Klondike, Horseshoe, Bismarck.

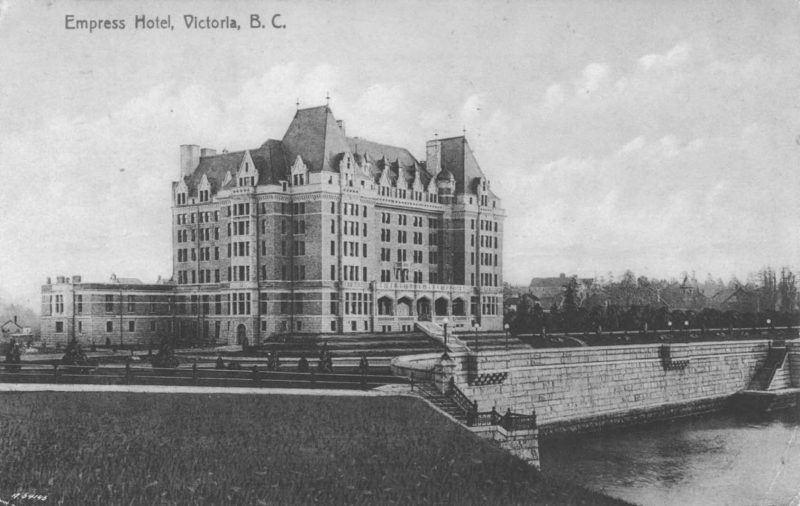

The completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway ushered in an era of international tourism with luxury hotels in its wake: the Driard, Empress, Western, Leyland, Balmoral and others. And, as Mofford points out, each found its special demographic niche according class, income, politics, profession, nationality, or just interest.

Competition in the liquor industry was fierce. Both saloons and hotels offered amenities well beyond their barrooms: banqueting halls, reading rooms, bowling alleys, billiard parlours, bathing facilities, some even free meals (with purchased beverages). Simeon Duck, a stone-mason by trade, provincial politician and some-time minister of finance, built the prestigious Duck Block on Broad Street which housed the Canada Hotel Bar and Grill, snooker parlour, meeting hall of Knights of Pythias, and facilities of the Pacific Athletic Club along with his carriage company and a bordello on the upper floors.

Of particular interest is the number of women active in the industry as investors, owners, and also very successful managers. Some establishments were husband and wife partnerships; widows inherited and ran the business until it could be sold. But some were pioneer entrepreneurs.

One of the most successful female bar owners was Margaret J. G. White who, over an extensive career, operated a saloon, the Victoria Theatre and four hotels. Her last was the prestigious Balmoral Hotel which she operated from 1896-1903, owning it until 1912. The Balmoral Hotel in Victoria made history when the suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst walked into its bar and demanded service. Refused, she took the case to the B.C. Supreme court and won the right for women to drink in public bars of the Province.

Aqua Vitae is a well-crafted social history of a new type which demonstrates the power of on-line research supported by the proliferation of British Columbia historical data bases which can be mined for information. These range from the recently digitized British Colonist newspaper and B.C. Directories to on-line sites such as B.C. Vital Statistics and British Columbia Archives Visual Records.

Furthermore, the book itself is a distillation of the author’s long-running cumulative blog on the subject called History of Drinking Establishments of British Columbia: A history of the hotels, saloons, beer parlours, cocktail lounges and pubs of British Columbia from 1851 to today.

https://raincoasthistory.blogspot.ca

Each chapter is prefaced by a location map for the saloons and hotels discussed. Many are illustrated with historic or occasionally recent black-and-white photographs. The appendices include a quick-reference time-line, bibliography and index. The result is a very readable balance of entertainment, reference and original scholarship.

*

Martin Segger is a museologist and art historian whose career has included academic and administrative posts at the Royal British Columbia Museum and the University of Victoria. He has taught museum studies and art history at the University of Victoria since 1973. Author of numerous publications on the architectural history of British Columbia, he also enjoyed a long career as a gallery curator focusing on B.C. historic and decorative arts. He currently serves as honorary art curator for the Union Club of British Columbia, and Government House, Victoria.

Martin Segger is a museologist and art historian whose career has included academic and administrative posts at the Royal British Columbia Museum and the University of Victoria. He has taught museum studies and art history at the University of Victoria since 1973. Author of numerous publications on the architectural history of British Columbia, he also enjoyed a long career as a gallery curator focusing on B.C. historic and decorative arts. He currently serves as honorary art curator for the Union Club of British Columbia, and Government House, Victoria.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Comments are closed.