#24 Mike Agostini: The Usain Bolt of 1954

Mike Agostini: The Usain Bolt of 1954

by Glinda Sutherland

*

The Bannister-Landy Miracle Mile at the Commonwealth Games in Vancouver in 1954 is the subject of perhaps the most famous photo ever taken in BC, capturing that poignant moment when Landy looked over his shoulder as he was being passed by Bannister.

The world’s first sub-four-minute mile, as well as the heartbreaking plight of champion marathon runner Jim Peters of Great Britain–who entered Empire Stadium seventeen minutes ahead of his nearest competitor, ten seconds ahead of his world record time, only to deliriously collapse and wobble, so dazed he could not complete the race–have almost entirely erased the memory of another great athlete at the Vancouver games, the Trinidadian sprinter Mike Agostini.

Almost erased, but not quite…

Once upon a distant time Mike Agostini was the Usain Bolt of his era. Born in 1935 at Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, he was the first athlete from his country to win a gold medal at the Commonwealth Games when he won the 100-yard spring on July 31, 1954. He later became a Vancouver resident.

The news of Agostini’s recent death in May of this year is reason enough to record “Agostini-mania” in 1954. Not quite Beatlemania perhaps, and not deemed worthy of statue, but a phenomenon nonetheless.

As Glinda Sutherland recalls in her personal essay below, Mike Agostini, who won the the 100-year final in 1954 as the “fastest human,” was a mesmerizing presence, particularly for women.

Here is the story of how one girl’s infatuation eventually led her to write to him as a woman decades later and say, “By the way, over fifty years ago, when I was eight years old, I was in love with you.”

— Richard Mackie

*

When Vancouver hosted the 1954 British Empire and Commonwealth Games, I was but a little girl of six years. My father, Peard Sutherland, who had died in June of that year, had worked on publicity for the Games, so our family wished to attend the games in his memory.

I do remember we went to track events at the newly-built Empire Stadium; I can very faintly recall watching the Miracle Mile, called the Mile of the Century. Dr. Roger Bannister and John Landy raced to the hair’s breadth finish, both completing the famous race in under four minutes.

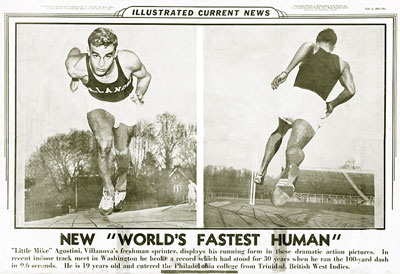

One week before the Miracle Mile, a young sprinter representing Trinidad and Tobago blazed to the gold medal in the Men’s 100 yards. His name was Mike Agostini and he had been catching world track eyes for some time. The nineteen-year-old phenom had already set records in the United States, including a world indoor record. When Agostini beat Canadian Don McFarlane and Hector Hogan of Australia in Vancouver, he solidified his position as a golden man of track and field.

But I hadn’t attended that event.

At age six, I still did not know anything about Mike Agostini.

After my father’s death, my mother, Dorothy, decided to build an apartment building in Kitsilano; in the spring of 1956, my mother took our sad and lost little family, my eighteen-year old sister Rill and me, now eight, to live in our new home. I hated my new school and I missed my old friend Ruth (Lorimer) James.

From our second floor windows, we could look out on the water and mountains. I could also look down on the lane below, which was adjoined by a duplex with a double garage. Upstairs from us was a roof deck that everyone wanted to see.

My sister’s friends were eighteen so they were “Big Girls” to me. They soon came to visit and Rill took them to the roof deck. I decided to tag along. The girls walked all round the deck to admire our grand view, while I stood back near the door, just watching them. One girl, Betty Bryden, moved over to the fence then looked down towards the lane. She burst into a shriek, “Look, it’s Mike Agostini! There is Mike Agostini!”

Having got to know Vancouver in 1954, evidently he had returned to live and work in the city where he’d won his gold medal.

In one sweep, the other girls moved towards Betty to see if they could see too. I did not move but held my place. There they were, peering into my lane, pointing and giggling and squealing with delight, as young women will with the sight of a beautiful young man.

I kept watching and finally uttered, “Who is Mike Agostini?”

They breathlessly told me, “He is a runner; he won the 100 yards; set a world record; he is the world’s fastest human – and he is just so good looking! He is a living doll.”

I walked forward to peer over the fence myself but by then he had disappeared. Had he gone into the garage? At that moment, I determined one thing — I would be the one to meet Mike Agostini.

After the day on the roof, I staked out my position. In the late afternoon, I would sit by the window, keeping my eyes focused on the lane and the garage doors — one was closed and the other was usually open revealing a table tennis set. My “child’s patience” was strong and several days later, he appeared.

I raced out of my house and began to ease myself very slowly across the lane. I was slight, very fair, and my almost blonde hair was drawn back into a little ponytail. I was very shy but my eight-year old determination was complete and intact. I stared at him for a moment. He came forward and smiled at me.

“I am Glinda Sutherland,” I said. He asked me where I lived. I pointed up to the apartment. I didn’t say much more, but I watched him and he was very beautiful. He had bronzed skin, smiles for me, and eyes that to me looked forever.

I would visit whenever I saw him, pretending to watch the table tennis games. He seemed to be laughing with life. There were always girls with him — girls of about eighteen. I did not like them at all, in fact I absolutely hated those girls! But very often he would give over his play to talk to me. He would walk forward to begin a little conversation, “How is school? What are you working on?”

He did not always have to look down to speak to me; sometimes he bent his knees, those beautifully formed knees, lowering his body so that his eyes were level with my own. Then, he asked, “Is that better? Now can we talk?” His eyes concentrated on my response as he kept the lowered height for a few moments, long enough for me to know that I was a very special person in his life.

But those older girls: they just tried to interrupt or prevent conversations. This was a problem. My sister’s friends had already told me that when he worked at the Men’s Wear department at the Hudson’s Bay store downtown, groups of girls would descend to gaze at him.

Our neighbour was Jack Harrison, a police inspector, track coach, former Olympian and, as the owner of the duplexes, Mike’s landlord. He was a giant of a man in both physical size and heart. One day he said to me, “I hear that you have met Mike.”

Mike Agostini was studying at Fresno State in California but came home from time to time to stay with Jack. And I absolutely adored Jack both as our friend and as a glorious source for information about Mike Agostini. I tried not to appear too eager but Jack always seemed to know what I needed to know.

My own knowledge of track and field was developing on its own. We had subscriptions to both the Sun and the Province, so when I got in from school, I would rush to lay the papers out on the living room floor. My scissors were at the ready. I would read the sections on track and field then take my shears to cut around the pictures and articles. Through the years 1956 to 1958, Mike Agostini articles were aplenty and they all ended up on my wall.

The first newspaper clipping appeared on my wall in 1956. I climbed onto my bed, moved on my knees towards the headboard. As I leaned forward, fingers clutching the clipping and tape, to carefully affix the article in place with my eight-year-old arms. I moved back on the bed to look at the article with a photo of Mike Agostini.

After the cutting each new article, I would take the tape and place the precious article in a remaining vacant place over my headboard. In time, the articles almost met the ceiling.

One could read headlines such as, “Mike in the US,” “World’s Fastest Human,” “World Records in 220 yards/200 metres,” “Double Finalist in the Melbourne Olympics of 1956.”

The newspapers carried pictures of Mike running, but they very often used the same photograph — the one that became my special one: a black and white picture of his face taken almost at an angle, from the side. His hair was very short and it showed itself as a black frame to his face, eyes laughing at the camera, the face that I knew so well. When I looked at that photograph and watched those eyes looking back at me. I thought to myself, “Those eyes and smile are mine. And he is my friend.”

Now that I had my special friend, Mike Agostini, I was set. This was massively exciting, not like the regular little companions at the school, and Mike was not like their friends. He was famous and very often away, but his picture appeared in the paper almost every day. I was so very lonely, but with articles arriving constantly it was almost like a having a visit.

One day, Jack turned to me and said, “Mike is in Trinidad. Why don’t you write him a letter and then you can say everything you want?”

I carefully wrote out the address and penned the letter. Jack was to assure me later that my letter had arrived safely but Mike was just leaving the island. By this time I was nine years old in 1957, very ready to turn ten. Mike had named me his “little girl friend,” so at least I had a title.

There was one occasion when Mike Agostini visited his little girl friend in her own house when Jack brought him over to visit me and my family. The twenty-two-year old athlete walked round our living room and then lay face-down on the carpeted floor, a cushion under his chin, for the duration of the visit while he talked about where he would live and run. There was considerable consternation about his plans but I could hardly concentrate — there he was on our floor!

I decided that I must be in love. I had absolutely no idea about love or lovers, but a clue came from a film released that year with a song called “Tammy.” The young woman in the film sat by a window singing, “Does my lover feel what I feel when he comes near?” This was the feeling I had. “Tammy, Tammy, you love him so, Tammy, Tammy, can’t let him go.” Now I understood. I sat by my own window, stuck my head out to sing the words, “You love him so, can’t let him go.”

To celebrate British Columbia’s 1958 Centennial, Summer Games were held at Empire Stadium. My sister, Rill, told me that she would take me to see Mike compete. It was thrilling because I had never before seen him run.

After the meet, we walked down to the track field to find him. When he saw us, his face broke into that smile and he rushed over to greet us. I was wearing a little locket round my neck, which he gently opened. “Mum and Dad,” he said, looking in to my eyes.

I was almost eleven years old. Mike had told me that when I was eighteen, he would take me out on a date, which now seemed almost within reach. But for now, another parting and I looked into those eyes, the eyes that looked forever. We bade farewell.

In 1958, Mike Agostini represented Canada at the British Empire and Commonwealth Games in Cardiff, Wales, taking a bronze medal in the 100. After that, he was to come back to Vancouver, but as time went on I began to think that his return was taking a very long time. Then, one day Jack came over to see us and said, “Mike has moved to Australia.”

I felt the very worst pounding in my ears and my heart. I thought, “I shall never forget this, ever.” I could not believe that he had left, and for many months I sat by my window and looked down at the garages. Sorrow stayed with me for a very long time. The clippings eventually came down from the wall to be tossed away, even the one bearing my special photograph, but all my thoughts of the young man from Trinidad were sealed and contained in that one little picture.

Jack told me later that Mike had gone into teaching and then sports broadcasting. In 1961, I read his article in Sports Illustrated, “My Take-Home Pay as an Amateur Sprinter.” By that year, I was well into secondary school with a new friend, swimmer Mary Stewart, a natural choice for me as a veteran reader of the sports pages. By the time of the 1962 Commonwealth Games, in Perth, Australia, Mary was a seasoned competitor; she had set an outstanding world record in the butterfly that July, so the Canadian press were well on to Mary’s chances for a gold medal.

Like a mad fifteen year old, I pestered my friend, “Please see if you can find Mike Agostini”.

Mary did come home with the gold! But she let slip that Mike had not quite remembered my name.

Throughout the years, I would occasionally think of the long-ago little girl. Someone would ask, “And how did you learn about track?”

And if I ever met a Trinidadian, a smile would be brought to their face: “How did you know Mike Agostini?!”

My wistful memories, ready laughter, and some sense of loyalty reminded me that someday I would try to find him.

*

I knew that Mike had become a well-known author in Australia and I was able to find a mailing address for him. As the 2008 Beijing Olympics approached, I felt that the time had come — the time to find this long-ago friend.

One morning in early 2008, I received a call from former Olympic swimmer and world record holder, Mary Stewart McIlwaine. “Glinda,” said my long time friend,” I have found my diary from the 1962 Commonwealth Games in Perth and there is a note which says, I met Mike Agostini.” My response was immediate, “I am going to write to him.” Mary’s words came just as quickly,” “He would love it!” A few months later, Mary inquired about the letter. “I shall know when the time is right,” I said.

By July, the urge to write had deepened. It had been fifty years since I had stood before him on the field at Empire Stadium. Now, I wondered if the famous sprinter could ever recall, from his Vancouver days, the little girl who lived across the lane. And indeed, it had been exactly fifty years ago.

I wrote to him on 13 August 2008. I described some scenes of those early days and was able to recall almost exactly the address of his home in Trinidad. “Can it be that I can really recall the names,” I asked myself. “Certainly, it is not perfect — after all, it was fifty years ago.”

In my letter I simply touched upon my childhood attachment, not wishing to say too much. I concluded by asking him to respond if he wished, and I included my email address. How long would it take the letter to reach Australia?

In the evening of August 30, I paused to smile for a moment, ”I think he has the letter,” I said to myself. The next night when I opened my screen, the name, MIKE AGOSTINI appeared. I began to read, “Thank you for your delightful letter which has prompted me to respond immediately.” In those moments, my heart and spirit were holding on to each other. He continued, “Australia has been my home since 1959 — although it might as well have been Vancouver.”

He went on to say, “Your memory of my address in Trinidad is astonishing.” And he wrote of Jack Harrison, “He is still that wonderful person he has always been and also my oldest living friend in the world.” He closed by asking more about my own life, “so that I might get a clearer perspective.” It was a very generous and welcoming letter indeed.

Soon after receiving the letter, I had to write to Mike to tell him the sad news of his friend Jack’s death at the age of ninety-nine years.

It was not until well into 2009 that I finally wrote him the letter about my own life. I acknowledged that with his international track career, academic life, and many women admirers of the time, he could not be expected to remember me. I wrote, “How could you know that this child had chosen you for her special friend?” Our correspondence continued and he invited me to call him “any time.”

I sat down to write the first draft of this story in August 2009. As I set to work, the crisp little black and white newspaper clipping came to my eyes: the photograph. It was as though it had been held safe in time’s locket, waiting to be opened once again, this memento from a little girl’s years that now jumped forward to my memory’s present.

The most important person for me to tell was Mike Agostini himself, and by September I made a deadline to make the telephone call. My anxiety was massive for, in a sense, I did not know him and here I was ringing up to say, “By the way, over fifty years ago, when I was eight years old, I was in love with you.” I felt it was worth pursuing both to honour my first love and for some kind of personal closure.

I put off the call for a couple of days, creating semi-comforting excuses, until the determined eight-year-old inside me took over and pressed the numbers for Sydney, Australia.

“Hello,” said the voice.

“Hello, may I speak to Mike Agostini.”

“This is Mike Agostini”

“Mike, this is Glinda Sutherland calling.”

“Hello, Glinda Sutherland!”

I told him the whole story of my deep infatuation. It was the strangest of sensations to be speaking to him, to be bringing the tale home to him.

He received it with amazement, tenderness, and laughter. At one point, he interrupted me and told me what so many others had told me already: “Glinda, you must write this story!”

After a year of many telephone conversations, I travelled to Sydney to visit with him — our first meeting in fifty-two years.

My story’s dream had stepped into reality and I had to pinch myself to find out if I am there. To me, he looked the same, the eyes that laugh more softly now, but legs that still look as though they can run.

In the evening, I took his arm for the walk through his park, the walk before dining. I looked over at his face as his eyes found our way through the dark paths. As we walked, I thought of the little girl inside me. She would not have had this any other way.

In the afternoons, Michael stood by as I looked through the old scrapbooks, the ones his father kept during his running years. He watched my hands turn the pages of the yellowed and fragile paper. My eyes kept looking for “the photograph” — then I turned the page and there it was. I leaned down to search its details more carefully, and

then I sat back as a shiver embraced me. It was the little photograph I had not seen in fifty years. I placed my fingers gently by the paper as my body gave a slight shake. Tears from my childhood met the beginning of my smile.

“No one has ever looked at my clippings in the way that you do,” he said.

*

Glinda Sutherland was born, raised, and educated in Vancouver, B.C. After graduating from UBC (Sociology ) she worked in the women’s movement, serving as Ombudswoman for the Vancouver Status of Women. In the early 1990s she served on the Board of Directors for the West Coast Women’s Legal Education and Action Fund. She then managed her mother’s apartment building until retiring in 2005. She is working on two books: Finding The Ombudswoman and Landlady Red, Landlady Blue.

*

[In 2014, The British Columbia Sports Hall of Fame hosted a special reception for the launch of their exhibition to commemorate the sixtieth anniversary of the 1954 British Empire Games in Vancouver. It was called ‘A Week You’ll Remember a Lifetime: Celebrating the 60th Anniversary of the 1954 British Empire and Commonwealth Games.’ Glinda Sutherland attended the reception. Also invited was Trinidadian-born Wilbur Walrond, who had conducted a fund-raising programme to give the gift of a trip to Vancouver to Mike Agostini. This was supported by The B.C. Sports Hall of Fame. Mike Agostini wrote the organizers to say he was not well enough to make the trip. On 12 May 2016, Mike Agostini died of pancreatic cancer, knowing how loved he was by so many people in British Columbia, especially one person in particular.]

8 comments on “#24 Mike Agostini: The Usain Bolt of 1954”

Dear Glinda, I hope you get this. I was at school with Mike from 1942 going forward to 1952 and can tell you things about him that are certainly not in all I have read from you and Wikipedia. He got expelled from school to be able to spend more time running, then in 1952 beat Herb McKinley in Jamaica. Herb was the winner of the 100 yards in the Olympic Games that year in Helsinki. Herb told him he could get a scholarship to go to University in California but he would have to get the equivalent of our Senior Cambridge examination. It was catholic school and he had to beg the principal to accept him back. He was eventually accepted at Villanova and then Fresno. There is plenty more I know.

I’m a second cousin to Mike Agostini and sprinting certainly runs in our family. My uncle ran for Ohio State, his daughter had a track scholarship at St. John’s University, and my cousin ran in the senior games at the Penn Relays

Dear Mark,

How lovely to see your message.

It is amazing to me that people are still finding my little story. Thank you for writing.

Glinda Sutherland

Ok, this is one of the most heartwarming stories I’ve read in years!

Beautifully thought out as memories flow back through the years to become words.

Thank you for sharing this amazing tale.

Dear Dan,

Thank you for your lovely comments.

I am delighted that you enjoyed this piece. Mike Agostini died in 2016… he loved this story too!

There will be more stories from me in the time to come.

Comments are closed.