Slinging hash up north in the ’80s

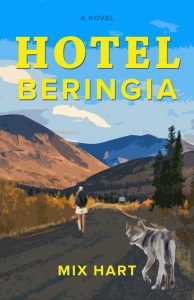

Hotel Beringia

by Mix Hart

New Westminster: Tidewater Press, 2024

$24.95 / 9781990160387

Reviewed by Trish Bowering

*

When I was young and learning how to be an adult, I never had a great adventure away from home. Consumed with my university studies, local work in the city suited my needs and I never really left. I’ve not set foot in the far North but have always wished to visit. All this is to say, I was particularly excited to dive into a novel that promised to showcase a Yukon coming-of-age story in the 1980s. Oh, did I mention that I was a child of the ‘80s?

Mix Hart’s new novel blends self-exploration and wilderness adventure in Hotel Beringia. The novel’s hotel sits hundreds of kilometres north of Dawson City, on a remote stretch of the Yukon’s famed Dempster Highway. It’s a waypoint for adventure travellers, and temporary home to highway workers, miners, and even scientists studying the Arctic tundra. Sisters Rumer and Charlotte, city girls fleeing parental bonds and disaffection with university studies, have taken summer waitressing jobs. The Beringia provides a clean break for the summer but may not prove the escape they hope.

The novel starts strongly. We meet the sisters stepping off the plane in Whitehorse. Written from Rumer’s first-person perspective, we learn that Charlotte is fleeing academic failure. The younger Charlotte is clearly the rebel, “probably more dangerous than she’s ever been,” and as the plane alights, “her mood is silent in its fury.” Rumer, a journalism student, is questioning her future and notes, “Until I figure out what my next life move is, I am a writer.”

Rumer has a naive quality, picturing herself as the heroine in her own story. Disembarking the plane, she says:

I descend the narrow stairs in a pleated miniskirt and strappy sandals, as a Hollywood star from another era might, I imagine, when arriving at an isolated movie location. The sky is different–softer–and the clouds too high above the earth, as though we’ve arrived on a neighbouring planet, farther from the sun. The wind is peppered with icy rain that whips my hair against my sunglasses and lifts my skirt. I stride toward the tiny airport, trying to absorb all the Arctic possible from the tarmac.

She writes in her fresh, crisp journal, “The rainbow is my talisman. I will survive this journey.” Her youthful enthusiasm begs the reader to wonder what is in store for these sisters as they step into the unknown.

The hotel workers who drive them twelve hours north to the hotel are gruff, provocative, and even reckless as they drink and drive up the Dempster Highway. At a pit stop along the way, Charlotte seems like a chameleon, one of the locals already: “The three of them are standing in a row, outside the van, hunched over like high school students smoking at recess on a chilly day. Somehow, in my five-minute absence, Charlotte has assimilated into the odd couple’s road-hard culture.”

By the end of the first chapter, there’s a satisfying undertone of menace as the sisters are set up as conflicted opposites, with a promise of huge personal growth and a reckoning to come. Hotel Beringia answers this promise with mixed success.

The novel is strongest in Hart’s descriptions of the natural world. Rumer, quickly frustrated with her job at the hotel and experiencing jarring interactions with her co-workers and the guests, often seeks escape in the Arctic tundra, with solitary walks north up the Dempster Highway—

I slip off my runners and step from the shale. My feet sink onto a damp, living carpet–a tangle of roots, moss, tiny leaves, and needles. There are so many spaces, textures, layers, in each luxurious step. I try to step lightly, like a caribou, yet I feel like a terrorist, annihilating a miniature world with each step. I slip silently across the spongy carpet until my feet connect once again with the sharp and dusty rocks of the Dempster.

As she takes up the desultory task of waitressing to patrons that range from indifferent to downright awful, one of the nicer men gives her advice: “given the choice between known and unknown paths, choose the unknown. It will scare the bejesus out of you, but it will be your greatest teacher.” Indeed, Rumer’s motto–and perhaps the overarching theme of this book–is “Walk toward wild.”

Okanagan resident Hart (Queen of the Godforsaken) absolutely succeeds in painting a “slice of life” portrait of a young adult who is at odds with her parents, her sister, and her choices thus far in life. Her sense of disconnection and unhappiness–mixed with a tinge of ennui–is palpable.

However, the novel fell short of my expectation for change and movement. Rumer’s youth is evident not only in her romantic journal entries but also in her marked judgemental attitude towards the people around her. A fellow waitress is, “that dumpy woman in the red skirt,” and her hair, “so dull I can’t even call it ugly.” Before we even get to know one particular portly guest who resembles Indiana Jones, Rumer dubs him “Fatty Jones.” Rumer’s derision would be more palatable if her character matured, becoming more adept at seeing the nuance in people rather than the black and white. Instead, her worldview, with its dislike of the hotel and the people in it, stays relatively static.

This is not to say that the folks inhabiting the hotel were uniformly a winsome bunch. Hart was able to effectively showcase Rumer’s experience of sexism that the sisters, and many of the women working in the North, faced. One colleague notes that the sisters were hired not just as waitresses, but as, “Klondike geishas.” Rumer bristles at the label, as she should, and there are some truly disturbing misogynistic comments and attitudes.

Another chance for Rumer’s character to develop might have occurred with a deep dive into the sisters’ conflictual relationship. Charlotte does make wildly different choices than Rumer during their summer sojourn, but after the first part of the book, her character remains largely off the page. Rumer has an overdeveloped sense of responsibility for her sister, reinforced by their parents. She’s resentful of it, but there is no intimate conversation or deep connection between the sisters, so the issue sits fallow, which was frustrating as a reader.

That said, I enjoyed some of the secondary characters. Small Seb, the son of a hotel worker, lent innocence and charm; and the gruff Ode, barkeep and tell-it-like-it-is powerhouse, was a presence who cut through the superficiality. Rumer has a romantic relationship that lends a satisfying arc to the story. Her beau is an ethically challenged scientist, but the dynamic allows Hart to raise truly important issues that have faced the North: environmental degradation, plunder and greed for the Arctic’s wealth.

As the novel moves into its final chapters, Rumer leaves the Hotel Beringia rather abruptly, moving to a denouement that finally allows the author an opportunity to show Rumer’s tentative growth. There is a reckoning of sorts with sister Charlotte, who has landed herself in Whitehorse in less-than-ideal circumstances, as Rumer comes to understand that she is ultimately not her sister’s keeper. Likewise, she negotiates the end of her summer relationship, one that is fraught with deceit and emotional peril. Possibly, Rumer is more apt to see the world in shades of grey rather than black and white: “…maybe I’ve accepted that truth, whether revealed or not, is always muddy.”

At the end, Hart takes us back to the beauty in the North, this time in the fragile construction of the human world. Walking alone along a Dawson City street as she prepares to leave, Rumer muses, “There is a beauty in old. Their histories are no longer contained within their decaying frames; their stories spill onto streets, seep into the earth and surrounding atmosphere, and into my consciousness. I walk slowly along the street–open to their stories–experiencing the odd, fleeting moments of joy, then arduous pain.” There is value in imperfect things. It’s a beautiful sentiment, and a vividly poignant observation.

Hotel Beringia had so much potential to showcase meaningful transformation for protagonist Rumer, but while the novel had its strengths in the evocative descriptions of the Arctic wilderness and a strong sense of place, it didn’t meet my need for narrative depth. In her Acknowledgements section, Hart speaks of her trips to the Arctic and of travelling the Dempster Highway. It’s clear that she’s speaking from her own experience as she pens beautiful descriptions of the Yukon. If there is one overarching theme that Hotel Beringia shouts loud and clear, it’s “Walk towards wild,” something well worth contemplating.

*

Trish Bowering lives in Vancouver, where she is immersed in reading, writing, and vegetable gardening. She has an undergraduate degree in Psychology from the University of Victoria, and obtained her M.D. from the University of British Columbia. Now retired from her medical practice, she focuses on her love of all things literary. She blogs at TrishTalksBooks.com and reviews on Instagram@trishtalksbooks. [Editor’s note: Trish reviewed books by Steve Burgess, Susan Juby, Myrl Coulter, Christopher Levenson, David Bergen, and Debi Goodwin for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” —E.M. Forster