1942 Teenage girls, ‘unredacted’

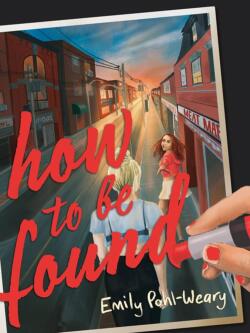

How to Be Found

by Emily Pohl-Weary

Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2023

$19.95 / 9781551529356

Reviewed by Rhea Tregebov

*

Emily Pohl-Weary’s YA novel, How to be Found, makes for propulsive, compelling reading.

Emily Pohl-Weary’s YA novel, How to be Found, makes for propulsive, compelling reading.

Sixteen-year-old best friends Michie and Trissa consider themselves sisters and offer each other both standard sisterly grief and fierce sisterly loyalty. Only-children to single moms, they have grown up together in a dilapidated brownstone duplex in Toronto’s tough Parkdale neighbourhood. Trissa is “the queen of not giving a shit,” as evidenced by the novel’s opening scene of her flashing the circle of friends gathered in an empty condo apartment. Meanwhile, Michie, the first-person narrator, has conducted a life constrained by chronic health issues: “Cardiac arrhythmia and asthma were two of the four million health issues I’d been born with.” The two couldn’t be more different: Trissa a risk-taker who makes extra money weekends as a cage-dancer at a local club, Michie a shy semi-invalid whose favourite pastime is reading A Girl’s Guide to Murder, a book she’s (bewilderingly, given her pacific nature) infatuated with. But despite occasional spats and grudges, their bond is unbreakable.

Pohl-Weary’s writing is deft and powerful. She animates her characters’ world with abundant sensual details, from the garbage-bin back alleys the kids roam to the bargain-bin clothing they wear. The author’s choice of first-person narration lets readers see this world vividly through Michie’s eyes. Pohl-Weary does excellent work capturing the point of view of this bright, likeable, self-aware but also self-conscious adolescent.

The author also excels at portraying her female protagonists’ various strategies to cope with the sexism that envelopes their lives. Michie describes the unwanted hugs from her high school history teacher as “horrid” but tolerates them for their practical value: “I’d made sure that [history] was my home room for two years in a row. Since he would try to hug me anyway, why not have a spotless attendance record in exchange?” Adult readers may cringe at the compromise Michie has struck with what she clearly understands as her teacher’s inappropriate behaviour, but the intended audience of young readers is likely less judgemental, recognizing as necessary the survival tactics these young women employ.

It’s not merely this relatively mild expression of sexism that the protagonists have to contend with. Vancouver’s Pohl-Weary (Not Your Ordinary Wolf Girl) portrays with shattering realism their vulnerability to the gendered violence surrounding them. In the opening chapter, one of the male teenage characters alludes jokingly to the West End Strangler, a serial killer whose victims have been young women Michie and Trissa’s age. And when, early in the book, the bold and daring Trissa mysteriously disappears, the girls’ vulnerability becomes explicit, a central concern of the plot, over which the shadow of this serial murderer hangs heavy.

In her recent memoir, Recollections of My Nonexistence, Rebecca Solnit addresses the culture of violence in which women live, calling it an “undeclared war,” and noting how “[e]ach death of a woman [is] a message to women in general.” While Pohl-Weary’s feisty, resilient young protagonists are capable of both declaring and engaging in battle in this war, the visceral challenges they face are chilling.

While the police are immediately informed of Trissa’s disappearance, rather than applying resources to finding Trissa, their main concern seems to be intimidating the already fearful and anxious family members. The scenes in which they descend on Michie and Trissa’s home are devastating. They treat Charlene, Trissa’s mother, like a suspect rather than a distraught mother, and wind up hauling everyone off to the police station in the middle of the night.

Rachel, Michie’s mother, suffers from lupus and in order to treat it, grows her own cannabis legally. In order to make ends meet, however, she also sells some cannabis product on the side (as well as some “organically grown” psilocybin mushrooms). The police are more focussed on pursuing these infractions than on finding Trissa, and Rachel herself ends up being arrested.

With the police worse than useless, Trissa vanished, Charlene incapacitated by grief, and Rachel under arrest, Michie’s on her own. Nonetheless, she resolves to find Trissa, no matter the cost or risk. The rest of the book unfolds as Michie frantically follows the baffling trail of Trissa’s disappearance, learning uncomfortable and frightening facts about the life of the sister/friend she thought she knew so well.

One of Pohl-Weary’s many strengths is her ability to create credible, three-dimensional characters, both in her teenage protagonists and in the adults who orbit their complicated and disquieting lives. Rachel and Charlene are identifiably human and humanly flawed. Candace, the mother of Michie’s love interest, Anwar, is a source of anxiety rather than support for Anwar, as she remains devastated by the accidental death of her young daughter in a hit-and-run car accident. Despite their faults and limitations, the adults in the book are not reduced to caricatures or villains.

The traumatizing event of Anwar’s little sister’s death, which occurred four years earlier, feels so central to the story—and to the psychological damage that all the main characters are coping with—that it’s tempting to want it to have been directly included in the narrative, rather than alluded to. There are other blips in the plot, some dropped threads and red herrings, that nonetheless do not impede our profound engagement with this fast-paced and captivating story.

Pohl-Weary notes on her website that How to Be Found “is probably my most autobiographical fiction yet,” and the authenticity with which she writes is gripping and deeply moving. While this gritty portrayal of the emotional and sexual lives of sixteen-year-olds may have adults who read the book wincing in concern, its piercing honesty is likely to resonate strongly with its intended teenage audience. It is also recommended reading for parents who would like a window into the unredacted lives of the young people they love.

*

Rhea Tregebov is an award-winning poet and the celebrated author of five children’s picture books as well as two novels, Rue des Rosiers (2019) and The Knife Sharpener’s Bell (2009). She lives and writes in Vancouver, where she is Associate Professor Emerita at the School of Creative Writing at UBC. She served as Chair of the Writers’ Union of Canada from 2021 to 2023. She is currently completing her eighth collection of poetry, which will be published by Véhicule Press in Spring 2024. [Editor’s note: Rhea recently reviewed Chelsea Wakelyn in BCR. Her Rue des Rosiers was reviewed in BCR by Paul Hendrick.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster