1902 Knowing the forest

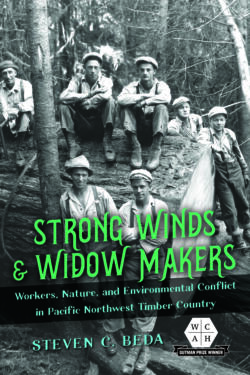

Strong Winds and Widow Makers: Workers, Nature, and Environmental Conflict in Pacific Northwest Timber Country

by Steven C. Beda

Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2023

$24.95 (USD) / ISBN 9780252086823

Reviewed by Gordon Hak

*

The book title might suggest that there is little of interest here for British Columbia readers, who often do not see British Columbia as part of the Pacific Northwest, but this is not the case. Steven Beda, a professor of history at the University of Oregon, casts a wide net, examining the relationship between the conservation and environmental movements, and workers in the coastal forests of the Pacific Northwest, a region stretching from southern Oregon to northern British Columbia, over the course of the 20th Century. British Columbians are part of the story, but even if the province had not been included at all, the book’s themes, perspective, and arguments would still be relevant to Canadian readers.

The book title might suggest that there is little of interest here for British Columbia readers, who often do not see British Columbia as part of the Pacific Northwest, but this is not the case. Steven Beda, a professor of history at the University of Oregon, casts a wide net, examining the relationship between the conservation and environmental movements, and workers in the coastal forests of the Pacific Northwest, a region stretching from southern Oregon to northern British Columbia, over the course of the 20th Century. British Columbians are part of the story, but even if the province had not been included at all, the book’s themes, perspective, and arguments would still be relevant to Canadian readers.

This is not a history of the forest industry overall or the lumber business or mill workers, but rather the focus is on loggers and their families in communities and camps near logging operations. These are not the loggers, often single, sent out from Vancouver hiring halls doing seasonal work, but the more permanent workers with families who lived year-round and raised families in the forest environment, in logging communities. They are a segment of the working class, but significantly also part of the rural world. This is the “homeguard” explored by Richard Mackie in his social history of the people of the Vancouver Island’s Comox Logging Company in the Comox-Courtenay area, a work which Beda draws on.[i] Notably, the bad guys in Beda’s narrative are not the loggers who work in the woods harvesting trees, at times facing off against environmental protesters. Nor are they the logging companies, though they were in the past, and their current logging practices still need to be carefully managed and monitored. Instead, in recent times the bad guys are the activists and supporters who constitute the modern environmental movement.

The book is divided into three sections. The first section examines the development of the logging industry and the establishment of logging communities to the 1920s. Companies encouraged community development and this took on a new urgency in the late First World War years, says Beda, when companies turned to corporate welfare policies, and most importantly, the establishment of families, to extinguish the influence of radicalism. In these family-centred towns and camps people were part of the forest environment. They were not just workers, and life in this environment was remembered fondly by participants, involving picking mushrooms and berries, and fishing and hunting, among many other pursuits, that were both pleasurable and important for survival. Children played in the woods. Moreover, these activities were social, enhancing a positive sense of community and place.

Beda also considers the relationship between the ecology of a forest and logging. Forests, he explains, are not static, but ever changing, naturally going through a number of regenerative stages, and logging can be part of this ongoing process. Indeed, for families the cutover land was more valuable in providing sustenance than the previous old-growth forest. Loggers and their families were conscious of the succession process in a forest’s history, “even if they never used the term, and often argued that they could survive off the forest precisely because it had been altered by logging.” Deer, grouse, and berries, for example, all flourished in the clearcuts.

The second section of the book examines the years from the 1930s to the 1950s, noting the emergence of a more pointed and political conservation mentality among loggers who experienced and witnessed unemployment in the 1930s and who became increasingly aware of the overharvesting of the forests, which suggested the impending demise of the logging industry, and as such the logging communities, if the forests were not better managed. The Co-operative Commonwealth Federation in Canada and New Dealers in the United States promoted measures to deal with these issues. This is also the era that witnessed the establishment of stronger unions in the woods, and Beda links this to the conservation impulse, claiming that forest-management issues launched the 1930s union movement in the woods. Beda develops this theme in his discussion of the formative years of the International Woodworkers of America in the 1930s, arguing that timber-working communities began to realize that they had a special relationship to the forest and that they had to work toward forest conservation to sustain both their way of life and the forest in the face of lumbermen and politicians who had no long-term interest in the forests. The post-war years saw a continuation of this alliance between workers and conservation advocates against the owners. In the 1950s the IWA in the United States allied with the Wilderness Society to enhance the protection of wilderness areas, to keep them from being logged, which might seem like an odd position for the loggers to take, but, says Beda, the IWA believed that setting aside land for preservation would force the companies to better manage the land that was being logged. However, this this link between forest workers, with their conservationist, multiple-use forest ideals, and wilderness advocates did not last, as the politics of the environmental movement of the 1960s moved from a conservation to a preservation perspective.

The third section of the book, which focuses on Washington and Oregon, examines the realignment of forces with interests in the forests, a rearrangement which pitted the new environmental movement, which was most committed to forest preservation–with little seeming interest in the lives of loggers and their families, or their culture and communities–against a new alliance that linked loggers, who were still committed to a balanced conservation, multi-use framework, and their employers. These erstwhile adversaries now stood together to preserve the lumber industry and lumber communities. The rise of the Northwest as an expanding affluent, high-tech urban region with an environmental sensibility was increasingly distinct from the poorer logging communities. The class divide of the first half of the twentieth century that pitted workers against employers, gave way to a rural-urban split, with working-class loggers united with the lumber-industry employers to protect their interests against the attack from city-dwellers.

In understanding this transition, Beda spends much time examining the popular culture of the 1960s and 1970s that increasingly saw traditional working-class people as rather ignorant and backward, and loggers, more specifically, as people mindlessly destroying the forests. Ken Kesey’s well-known 1964 novel Sometimes a Great Notion, which later became a movie, is given pride of place in this transition. Kesey was a high-profile figure in the counterculture of the 1960s. His novel is about a family of Oregon loggers, and the portrayal of the loggers was hardly flattering. Whereas loggers had once been seen as at the forefront of the conservation movement, they were now increasingly seen as a major threat to the forests.

Conflict came to a head in Oregon in the 1980s and 1990s over the preservation of the northern spotted owl, which environmental activists said was facing extinction due to the disappearance of old forests. Beda spends a full chapter analyzing the well-known conflict. He discusses the difficulties predicting the fate of the spotted owl after logging based on insufficient data, and the complications in defining a science-based old-growth forest. Significantly, he draws out the political importance of environmental groups changing their language from referring to “old-growth forests” to referring to “ancient forests.” The term “ancient forests” suggested that forests once logged could never be replaced: “Forests could be returned to old-growth status after logging, but once ‘ancient forests’ were gone, they were gone for good. More than that, ‘ancient forests’ suggested that the Northwest’s forests were part of the world’s shared history, something akin to antiquity, and that saving the owl and the ‘ancient forests’ upon which it depended was an act of preserving our common global heritage.” (p. 192) With the success of the environmental movement, there was a reduced harvest on public lands, and in logging communities crime rates rose as people lost jobs and social problems increased at the same time that rural county budgets declined. There was little sympathy from the booming urban and environmentalist communities.

In the end, Beda is optimistic about the future of the forests and the loggers’ world. He notes that climate scientists and forest managers see younger, faster-growing trees as able to capture more carbon more quickly than older trees. And instead of seeing technological change as the cause of much unemployment, the argument of many environmentalists, he regards technological change as potentially leading to more jobs overall in a technologically sophisticated lumber industry producing engineered lumber and relying on, say, wind power. And an expanding, democratically managed, sustainable logging and lumber industry could help mitigate the use of concrete, a very destructive material in terms of climate change, in building construction. He concludes that the history of the Northwest woods “should encourage us to see forests in new ways, not exclusively as spaces of industrial accumulation, as early twentieth-century lumbermen often saw the forests, nor as exclusively wilderness, as the environmental movement of the late twentieth century too often saw them, but as places with multiple uses and values, as people from timber country have long seen them.”

Beda adeptly employs memoirs and life histories in his story, and the descriptions of the woods, camp family life, and work in logging operations are engaging. British Columbia readers might wish that there were more details regarding the provincial War in the Woods in the 1990s, Canadian unions, the politics of left and right, local environmental groups, and the Indigenous context. However, it is the overall approach that warrants consideration: rather than seeing environmental conflict in timber country as simply the story of jobs versus the environment, as is often the case, this historical study views workers and environmentalism in relation to class, community, ways of life, understandings of nature, forest science, policy alternatives, politics, popular culture, and economics, producing a broader, more nuanced understanding of the topic.

[1] Richard Somerset Mackie, Island Timber: A Social History of the Comox Logging Company (Victoria: Sono Nis Press, 2000).

*

Gordon Hak is Professor emeritus at Vancouver Island University. He has produced two books on the British Columbia forest industry: Turning Trees into Dollars: The British Columbia Coastal Lumber Industry, 1858-1913 (University of Toronto Press, 2000) and Capital and Labour in the British Columbia Forest Industry, 1934-74 (University of British Columbia Press, 2007). In the last decade or so, his writing has been more involved with political questions. The Left in British Columbia: A History of Struggle (Ronsdale Press, 2013) is a historical study of the left in provincial politics, while Locating the Left in Difficult Times: Framing a Political Discourse for the Present (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017) discusses the anti-capitalism left in the western world. More recently, Liberal Progressivism: Politics and Class in the Age of Neoliberalism and Climate Change (Routledge, 2021), part of the Routledge series “Innovations in Political Theory,” examines the modern liberal-progressive left, which includes the broad environmental movement, evaluating it from the perspective of the more radical left and from the perspective of the traditional working class.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster