1834 Stuck in the middle of nowhere with you

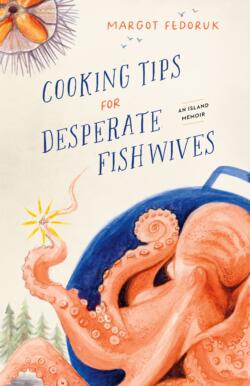

Cooking Tips for Desperate Fishwives: An Island Memoir

by Margot Fedoruk

Victoria: Heritage House, 2022

$22.95 / 9781772033953

Reviewed by Susan Sanford Blades

*

Cooking Tips for Desperate Fishwives, Margot Fedoruk’s island memoir, instantly captures her reader’s attention by beginning right in the thick of things: “The night I ran over Rick with my car, I was over four months pregnant with our first daughter.” Thus ensues an enthralling introduction, full of the despair of a woman whose husband, though well-intended, puts his passion for sea-urchin diving—which takes him away for extended periods of time—ahead of his wife and family. Fedoruk’s writing is honest and heartfelt, full of well-crafted descriptions, such as that of Rick, “moving in slow motion, silently like a crab, across the cold moonscape of the ocean floor.” This introduction is topped, as well, with a recipe for “Killer Lasagne,” the lasagne she had been preparing on the night in question. The book is scattered with recipes—most chapters end with one—the most meaningful of which stem from an incident she writes about in the book, and all of which add to the book’s heart. This is the only recipe I’ve tried so far but can attest it is, indeed, killer. After this introduction, though, and this is really my only qualm with the book, instead of continuing with the momentum she’s built, Fedoruk takes us back to her childhood. We won’t hear of Rick again until page 55, when Margot meets him while tree planting in British Columbia.

Cooking Tips for Desperate Fishwives, Margot Fedoruk’s island memoir, instantly captures her reader’s attention by beginning right in the thick of things: “The night I ran over Rick with my car, I was over four months pregnant with our first daughter.” Thus ensues an enthralling introduction, full of the despair of a woman whose husband, though well-intended, puts his passion for sea-urchin diving—which takes him away for extended periods of time—ahead of his wife and family. Fedoruk’s writing is honest and heartfelt, full of well-crafted descriptions, such as that of Rick, “moving in slow motion, silently like a crab, across the cold moonscape of the ocean floor.” This introduction is topped, as well, with a recipe for “Killer Lasagne,” the lasagne she had been preparing on the night in question. The book is scattered with recipes—most chapters end with one—the most meaningful of which stem from an incident she writes about in the book, and all of which add to the book’s heart. This is the only recipe I’ve tried so far but can attest it is, indeed, killer. After this introduction, though, and this is really my only qualm with the book, instead of continuing with the momentum she’s built, Fedoruk takes us back to her childhood. We won’t hear of Rick again until page 55, when Margot meets him while tree planting in British Columbia.

I don’t mean to say that her childhood isn’t interesting, and it’s not that it doesn’t play into her relationship with her future life partner (as all of our childhoods do, surely). We learn about her two sets of grandparents, her parents, the history of alcoholism and abuse in her family and her mother’s volatile relationships with men. It seems, though, that Fedoruk is working with two storylines that are joined by chronology but not theme. This book is a memoir that, at times, bleeds into autobiography. Given this, there are sections of the book that read like small vignettes that are only there because they were important events in the author’s life, but that don’t contribute to this book’s main purpose, which is to tell her and Rick’s strained love story.

Once we meet Rick, however, Fedoruk settles into the main storyline, the narrative relaxes a little and her writing shines through. It is thick with oceanic description, such as her “jewellery flashing like metal lures,” and draws the reader right into every scene. I could picture every image she paints in the book—at sea as his dive tender, in the various damp, ramshackle cabins she and Rick lived in on Gabriola Island, and even the dry chill of Calgary when they temporarily moved there during a failed attempt to keep Rick anchored in one place for a while.

This love story is as much about love as it is loneliness. I felt keenly the solitude of new motherhood Fedoruk felt, her desperation to talk to a grownup, to find other mothers to commune with, the disappointment when Rick finally came home with no energy left to meet the needs of his waiting, growing family. Paired with the isolation she felt due to Rick, though, is the community Fedoruk found on Gabriola Island. This book is a love letter to the West Coast, and to the little corner of the West Coast that Margot Fedoruk settled into on Gabriola Island.

Fedoruk describes her typical Gulf Island existence—trawling the recycling depot for exciting finds, competitively picking blackberries, making love in an apple orchard, patching together odd jobs such as cleaning houses and teaching children’s art classes with creating items to sell to tourists at the weekly market. She began by selling light switch covers and driftwood that she painted and finally landed on making soap, which she still sells at the Gabriola market. Most importantly, though, she found the communion she’d been looking for with the other women on the island. “During the summer, I sat under the shade of a spreading big leaf maple at Twin Beaches sharing parenting tips with the other moms while our babies crawled in our laps and put sand in their mouths. The older kids would lift up rocks to find tiny crabs or chase each other half-naked through the warm, shallow waters. I had found a community and it was incomparable.”

This book is the best kind of love story. It’s messy and real with equal amounts joy and sorrow. While reading, I felt like I was hearing confession from a friend—one who trusts me with her flaws, her vulnerabilities, her highs and her lows.

*

Susan Sanford Blades lives on the traditional territory of the lək̓ʷəŋən speaking people, the Xwsepsum/Kosapsum and Songhees Nations (Victoria, Canada). Her debut novel, Fake It So Real, won the 2021 ReLit Award in the novel category and was a finalist for the 2021 BC and Yukon Book Prizes’ Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize. Her short fiction has been anthologized in The Journey Prize Reader: The Best of Canada’s New Writers and has been published in literary magazines across Canada as well as in the United States and Ireland. Her fiction has most recently been published in Gulf Coast and The Malahat Review and is forthcoming in The Master’s Review New Voices section. Susan Sanford Blades recently reviewed titles by Pamela Anderson and Sheila Norgate.

Susan Sanford Blades lives on the traditional territory of the lək̓ʷəŋən speaking people, the Xwsepsum/Kosapsum and Songhees Nations (Victoria, Canada). Her debut novel, Fake It So Real, won the 2021 ReLit Award in the novel category and was a finalist for the 2021 BC and Yukon Book Prizes’ Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize. Her short fiction has been anthologized in The Journey Prize Reader: The Best of Canada’s New Writers and has been published in literary magazines across Canada as well as in the United States and Ireland. Her fiction has most recently been published in Gulf Coast and The Malahat Review and is forthcoming in The Master’s Review New Voices section. Susan Sanford Blades recently reviewed titles by Pamela Anderson and Sheila Norgate.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster