1771 Specific to the Okanagan

Ghosthawk

by Matt Rader

Gibsons: Nightwood Editions, 2021

$18.95 / 9780889714045

Reviewed by Kelly Shepherd

*

In what is probably one of the earliest examples of ecopoetry (“Smokey the Bear Sutra,” 1969) the American poet and environmental philosopher Gary Snyder describes the presence of several “great centers of power” throughout the North American continent. The geographical locations he lists, including Walden Pond and Big Sur, among others, are also places of significance in American literature, for example Thoreau’s cabin in the woods was famously located next to Walden Pond. But this begs the question: are these places centres of power because they appear in prominent pieces of writing, or do they appear in the writing because they’re centres of power?

In what is probably one of the earliest examples of ecopoetry (“Smokey the Bear Sutra,” 1969) the American poet and environmental philosopher Gary Snyder describes the presence of several “great centers of power” throughout the North American continent. The geographical locations he lists, including Walden Pond and Big Sur, among others, are also places of significance in American literature, for example Thoreau’s cabin in the woods was famously located next to Walden Pond. But this begs the question: are these places centres of power because they appear in prominent pieces of writing, or do they appear in the writing because they’re centres of power?

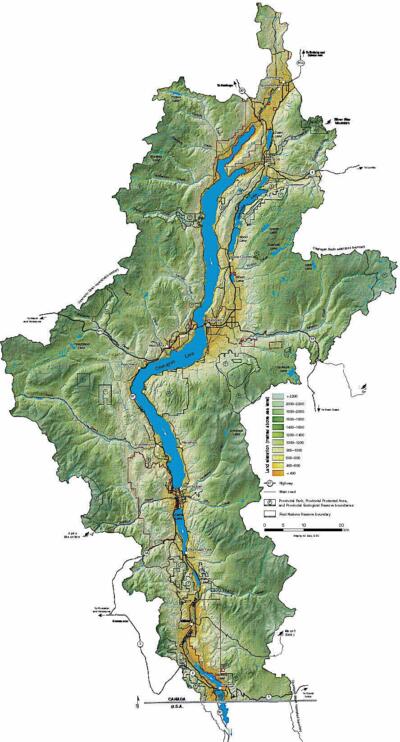

Either way, I think it’s an interesting idea, and (whether we take it really seriously or not, because it’s not clear if Snyder was taking it entirely seriously himself), I wonder if this “centre of power” designation might also be applied to BC’s Okanagan Valley. Because why are there so many poets in this particular area, with a relatively small population? The impressive list of Okanagan poets includes Jeannette Armstrong, Nancy Holmes, Jake Kennedy, John Lent, Lori Mairs (who is sorely missed), Harold Rhenisch, Natalie Rice, Laisha Rosnau, Michael V. Smith, Sharon Thesen. And I know I’m leaving out several others. Musicians and songwriters, like Herald Nix, should also be mentioned here.

Do poets and artists just naturally gravitate to warm weather and vineyards? Or is there more to it than that? Is the Okanagan actually a hotbed of poetry and creativity because it’s a centre of power? I’m not going to answer this question, which might after all be unanswerable; but I think it’s a good way to start a conversation about Ghosthawk. Rader hasn’t lived in the Okanagan as long as some of the writers listed above, but these poems are proof that he is putting down roots, so to speak, in the valley.

*

In 1986 Tom Wayman published “Articulating West,” a poem that describes a May drive from the Prairies, through the mountains, into British Columbia. The speaker’s eventual destination is Vernon, in the Okanagan Valley. And it’s a poem about transformation: along the way the air and the landscape change, orchards bloom beside the roads, and everything becomes greener. This is a familiar enough observation. If you’ve ever made that drive, then you’ve experienced the striking transition — a shift from winter to spring, or from spring to summer — that takes place in a single day.

Wayman’s poem takes a surprise turn, though, when the poem’s speaker (the driver of the car) notices that vegetation is also proliferating inside the vehicle, including “tendrils and stalks and unfolding leaves / poking out of the glove compartment / and around the edge of the floormats.” The accelerated change of seasons, from Prairie snow and grit to Okanagan warmth and greenery, is all-encompassing. The car and its driver are overwhelmed with vegetation. The car’s front end disappears in foliage, the passenger seat turns into a blossoming flower bed, and the tires become tree trunks. The entire vehicle is broken down and transformed, from a speeding metal machine into a slowly rolling garden. By the time the speaker arrives in Vernon, his car has fallen apart entirely, and he is “left sitting / in a pleasant arbor.” The poem ends with the line, “all I could say / by way of explanation / was: / I’m home.”

I mention this poem as an introduction to this discussion of Matt Rader’s 2021 book Ghosthawk, because this book is also filled with green and growing things, and because it’s also about transformations. And like Wayman’s “Articulating West,” Rader’s poems are specific to the Okanagan Valley: Rader lives in Kelowna, and teaches Creative Writing at UBC Okanagan. This is a book about a person’s relationship to a specific place, but these are not simply idyllic landscape poems. There are also hints of regret, and depictions of illness. And there is tension, exemplified in both the opening images of snakes (pp. 13 and 27) and in the closing image of a taut kite string, a “quivering line of gravity” (p. 119). And indeed the lines themselves should be paid attention to in this collection: the poems are mostly composed of short stanzas, but the deliberate line-breaks and occasional enjambment means the pages are more densely packed than they first appear.

This collection includes many memorable depictions of the natural world, for example the description of the way a bat can “origami / evening air // into its own image / and send it / hurtling // through darkness” (p. 116). Is the bat folding its wings, or is the night folding itself around the bat? And what is hurtling: the bat or the evening air? Either way, when you encounter the word “origami” used as a verb, you have to slow down, and reread the line. Elsewhere Rader captures the feeling of surprise when confronted by the sheer otherness of more-than-human beings: “the sudden animal / that’s so much // itself it can only be imagined / as something else” (p. 105). Like the bat, the “sudden animal” is hard to pin down. And so it should be! And why, Rader seems to be asking, would we even try?

But more than anything, I was reminded of Wayman’s green metamorphosis because there are so many botanical references in Rader’s book. Wayman’s “Articulating West” is an impressionistic depiction of the Okanagan region in the springtime, and especially its welcoming climate and abundant flora; the speaker in Rader’s poems identifies even more personally and intimately with the valley’s plant life. At one point, he claims that the names of flowers “title all [his] feelings” (Rader, p. 23). Some of the many flowers named in the pages that follow are mariposa lilies, forget-me-nots, buttercup, morning glory, and yarrow. Other vegetation, including lichen, ponderosa pine, sagebrush, snowberry, and thimbleberry also appear throughout these poems.

These plants are described realistically, with a naturalist’s eye; many of them are also utilized for their symbolic or metaphorical qualities. The book’s cover art depicts a mythical, combinational figure made up of human, butterfly, snake, and flower. And its single watchful, perhaps mournful, green eye gazes out at the reader from the centre of an Arrowleaf balsamroot blossom. This particular flower is significant, partly because of its beauty — in the spring months these blossoms cover the rounded hills and slopes of the Okanagan like constellations in the night sky — and partly because of its usefulness, and its cultural importance. The entire plant is edible: it’s a staple food in the Syilx people’s traditional diet. This species also has symbolic value, because it’s a sunflower: a symbol of the sun. In one poem, the sun is referred to as “the giant reactor / the balsamroot // modelled its flower on” (p. 89).

An interesting common thread in these poems is the image of repetition, and regeneration, which resembles what Mircea Eliade, the great Romanian scholar of religions, called the “Myth of the Eternal Return.” Among other things, this is a refutation of the linear approach to time that modern Western society has adopted, and a reminder that the natural world does not operate that way. “Nature does not travel in straight lines,” as someone once said, and neither does time. Rather, everything moves in circles and cycles. Eliade cites dozens of Indigenous and traditional cultures around the world who view the world, including human life and the passage of time, in this cyclical pattern. This thinking calls into question our modern notions of “progress,” and even our understanding of the self as a distinct and separate individual.

While not all these ideas are stated explicitly in the poems of Ghosthawk, their speaker clearly identifies with flowers and plants, and specifically with their cycles of death in the winter, and rebirth in the spring. Images of repetition, return, and regeneration appear throughout the book: in one poem the speaker remembers the “exact moment / we reincarnate as ourselves” (p. 78); elsewhere he asks, “[w]ho comes back / exactly / as they were?” (p. 111). And reincarnation, or rebirth, is alluded to in a description of a forest: “being born / a million times without / death, without / end” (p. 112). Butterflies and snowflakes are called “fractal” (pp. 20 and 41, respectively), and a quaking aspen tree, with its “quiver of selves,” proclaims “[h]ere I am again, and again, / and again” (p. 81). These are descriptions of plant life and the natural world, but the human speaker continues to identify himself with the flora, and the line between them is never entirely clear. The phrase “the liver will regenerate” (p. 60) is one of several references to an illness or malady that is never clearly explained, but it uses the same language of return and rebirth.

These recurring cycles and returns, along with the speaker’s claim that “each / disruption / of the pattern // is a new pattern” (pp. 45-46), prompted me to look for larger patterns within the book itself. And indeed, the entire collection is arranged in a repeating pattern. There are five sections, with differing physical shape of the poems on the pages. The first and fifth sections are “stand-alone” poems, with titles, in tercets with very short lines. The second and fourth sections are suites of short, untitled poems, in long horizontal couplets. And the third, or middle, section is a suite of prose poems, blocky-looking stanzas like paragraphs on the page, with ten lines each. Considering the preponderance of plant and flower imagery throughout the book, and the sun / sunflower imagery in particular, this larger symmetrical or repeating form itself might be seen as a flower: the poems in tercets are its various leaves, the long thin couplets are stem-shaped, and the prose poems in the centre are the blossoms. “I give you now / the face // of the sun / in a diaspora of leaves” (p. 117). “Leaves” can also refer to pages. Is this line meant to be a picture of the entire book?

But I may be wandering too far afield here; Rader may never have intended anything resembling this pictorial meta-interpretation of his manuscript. Regardless, it’s an intriguing collection and I’m sure I won’t be the only reader tempted to approach it as some kind of puzzle. And even if you don’t read them that way, these poems provide some wonderful glimpses into the process of deeply connecting, through careful observation and imaginative engagement with its flora and fauna, to a place. To quote the speaker of Tom Wayman’s “Articulating West” poem, “I’m home.”

*

Kelly Shepherd’s second poetry collection Insomnia Bird (Thistledown Press, 2018) won the 2019 Robert Kroetsch City of Edmonton Book Prize, and it was shortlisted for the 2019 Stephan G. Stephansson Award for Poetry. Kelly has written eight poetry chapbooks (the eighth is forthcoming from The Alfred Gustav Press), and he is a poetry editor for the environmental philosophy journal The Trumpeter. Kelly has a Creative Writing MFA from UBC Okanagan, with a thesis on the intersections of work poetry and ecopoetry, and an MA in Religious Studies from the University of Alberta, with a thesis on sacred geography. Originally from Smithers, he currently lives and teaches on Treaty 6 territory, in Edmonton.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster