1718 The rhetoric of Imitation Crab

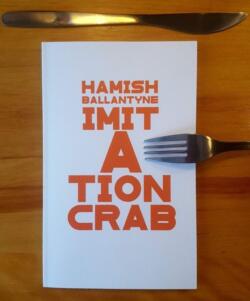

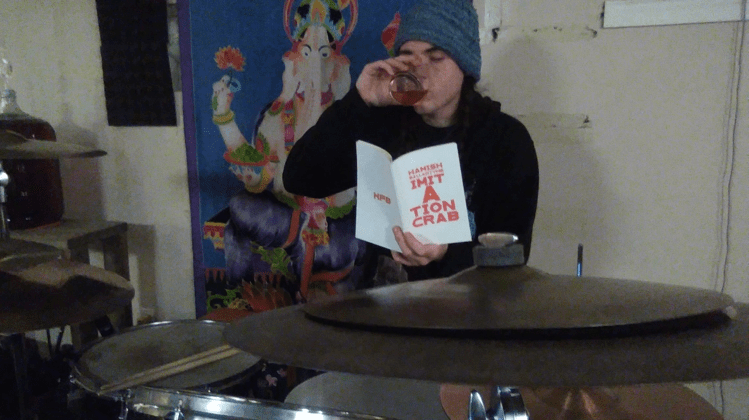

Imitation Crab

by Hamish Ballantyne

Toronto: Knife/Fork/Book, 2020

$15.00 / 9781989355268

Reviewed by Terry Trowbridge

*

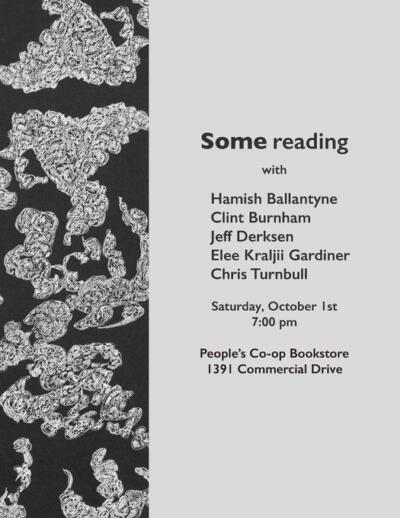

Rhetoric in Hamish Ballantyne’s Imitation Crab and Future Literacy in Canadian Publics

Rhetoric in Hamish Ballantyne’s Imitation Crab and Future Literacy in Canadian Publics

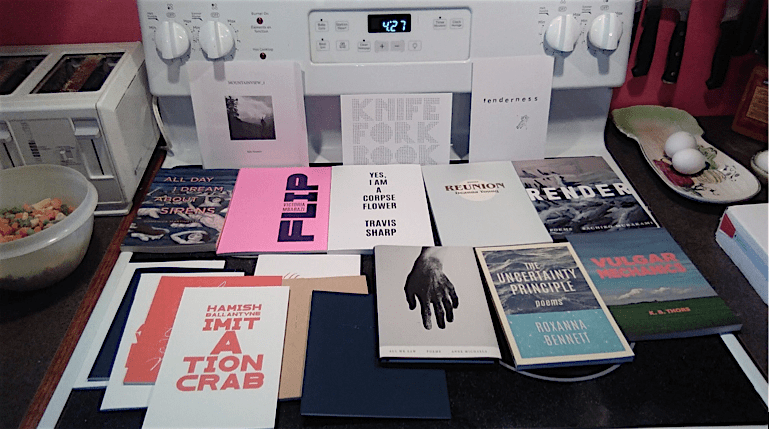

In the Autumn of 2022, Toronto publisher Knife/Fork/Book restructured their operations. They closed their street-level bricks-and-mortar retail store, opting for online sales and to focus more energy on the annual poetry festival Fertile Festival of New & Inventive Works. Part of Knife/Fork/Book’s restructuring process was to offer extraordinarily discounted bundles of books called feasts (Kirby, 2022a, 2022b). Canadian readers and writers enjoyed unboxing and sharing pictures of their feast books online, surprised by the volume of volumes, especially high-quality chapbook art that was as much visual treats as they were texts. Hamish Ballantyne’s chapbook Imitation Crab, published by Knife/Fork/Book in 2020, was part of many feasts that were sold. Thanks to the sale and its timing, Ballantyne’s chapbook is now in wide circulation on collector bookshelves and, presumably, circulated once more thanks to holiday gift-giving traditions across the country.

Hamish Ballantyne’s tone fits the late-Autumn tone of unboxing feasts. The poems parallel gothic horror, the Twin Peak-y ominousness, that hints at oncoming seasonal depression, while entering Iqaluit, leaving Montreal, visually scanning twilit Kentucky forest backroads. Poetry chapbooks do not need to be read in the order that their pages are numbered, but in this case, Ballantyne sets a tone of passing time. Some short poems squeeze into the top left corner of long pages of white space. Other poems are formatted with hyperbaton that places phrases and words on the page in a manner that turns the act of reading into the unfolding of time, in the style shared by (for example), Earle Birney and John Terpstra.

Some of the poems are phenomenologist writing. They meld the unfolding of time with the ungrammatical internal monologue of a narrator half-lost in thought, through the use of hysteron proteron (syntax or sense out of normal logical order) bordering on Dadaism. The longest poems include anastrophe through strikeout font reminiscent of Greg Betts, that implies indecisiveness and ambivalent amphibologia. Although, the second-last page reveals the entire chapbook might be dreaming with the lines, “dreamed crossing/so often/its traverse” (p. 40). Perhaps his use of hyphens and dreamwork is connected with Emily Dickinson’s syntax. All of this rhetorical analysis (drawn in loving abecedarian poicilogia from Lanham, 1991), is to say that Ballantyne’s English poetry is emotional, postmodern, and sets the pace for the reader’s heartrate and respiration through the use of typography and eerie pathos. The book is a paragon example of moody chronographia, description of time; and shoreline topographia, description of places.

Owls are repeating imagery of hunters and scavengers. On the first page, owls are “many hands/seek/murky vittles” trapped in tide pools and observe the narrator who hates to leave the night ditches of Gabriola Island and their fauna (pp. 1-9). Owls accompany synchesis where the mixed-up arrangement of words about time, cooking, and habitat pile up into a camping tableau (p. 12). Ballantyne channels David Lynch, “many crimes traced/back to the influx of/owls” (p. 20). The gizzard of owls in implied in “the right/solemn for /illness-for/news—” (p. 33).

Owls are repeating imagery of hunters and scavengers. On the first page, owls are “many hands/seek/murky vittles” trapped in tide pools and observe the narrator who hates to leave the night ditches of Gabriola Island and their fauna (pp. 1-9). Owls accompany synchesis where the mixed-up arrangement of words about time, cooking, and habitat pile up into a camping tableau (p. 12). Ballantyne channels David Lynch, “many crimes traced/back to the influx of/owls” (p. 20). The gizzard of owls in implied in “the right/solemn for /illness-for/news—” (p. 33).

A page of poetry about cormorants is ambiguously one or two poems. Ballantyne’s cormorants are comic foils, demonstrated with silly antistoecon when “small eggs” are substituted with “smool oggs” and the joyful plunge into water offers a not “wet dream” but the rhyming “wet scream” (p. 7). Ballantyne undignifies cormorants by using strikeout font and classical malapropism (vulgar error trough an attempt to seem learned), replaced with neologisms that would fit in Edward Lear’s Book of Bosh (1992), in the lines “brandt’s pelagic nor double-crested/renounce observation/go gumwiggle/my nets for fishies” (p. 7).

Even though Imitation Crab has gorgeous playful elements of style, the narrative arc to which it does justice tends toward seasonal sadness. It is a document of the English rhetoric of camping and rain, although with silliness suggestive of Bill Watterson’s take on camping and rain. Even when the poems offer the optimism of springtime, they are April in frozen Iqaluit. On one hand, Ballantyne’s verse “gasping/candlefish…recipe for sausage O/sole mio” (p. 25) parallels the verse of They Might Be Giants’ imagery in their cover of the song Fish Heads. On the other hand, when Ballantyne’s poems seem to be describing mountain hikers, they end “in the car/twenty times/to the same funeral” (p. 32).

The poems describe Kentucky, Montreal, Iqaluit, as places that Ballantyne has been to, but the British Columbia coast as the place where he belongs. He writes with more specific place names, like Trincomali Channel and Mount Tzuhalem. Both are features inside the Gulf Islands archipelago with few mapped pathways. As such, they indicate localized, insider knowledge of BC and writing to an audience that, in the spirit of his narrative, are also part of a British Columbian diaspora that has travelled afar and returned many times. (In that way, Ballantyne’s work is comparable to the autobiographical poetry of Catherine Owen and George Bowering).

Ballantyne does reveal that there are both provincial politics and uniquely local politics in the British Columbia where he lives. He writes of “local knowledge—/—island politics/donna nameless/trustee attended a secret ceremony/snuneymuxw the petroglyphs” (p. 36). The appearance of Snuneymuxw artifacts and ceremony in Pacific coastal island politics suggests that reading Imitation Crab with western traditional rhetorical devices of Richard Lanham (1991) is an insufficient literacy. What kind of meanings could be understood by a reader equipped with the decolonizing Indigenous poetics of Mareike Neuhaus and the skills of holophrastic reading (2015)? Someone recognized by both a common law Trustee and a nameless ceremonial title suggests legal pluralism (see: Aronson, 2022), and overlapping culturally specific meanings. As we readers simultaneously reconstitute our literary public, our local politics, and our post-pandemic worlds, hopefully someone can respond to Ballantyne’s poems with exactly that sort of holophrastic reading, or write an Indigenous counter-narrative that offers a synthesis of Ballantyne’s literary devices and holophrastic literature. Let us decolonize as we establish new literary societies and new supply chains.

Knife/Fork/Book was transformed during the pandemic. Now, in 2023, Canadian readers and publishers face the polycrisis (see: Lawrence et al., 2022). Knife/Fork/Book found a way to restructure their business while ensuring that their contributions, and other publishers’ work that were in their retail space, reached audiences and reviewers. Knife/Fork/Book ensured Hamish Ballantyne’s poetry will continue to be part of Canada’s literary conversations, although the discounts and shipping costs involved must have been a tense entrepreneurial gamble. That gamble gave reviewers more opportunities to read, review, and discuss the literary moment. So that the polycrisis does not overwhelm our culture, we need to review books like Hamish Ballantyne’s Imitation Crab so that our critical conversations can be part of the pandemic strata on which we build our future.

*

Terry Trowbridge’s poems have appeared in The New Quarterly, Carousel, subTerrain, paperplates, The Dalhousie Review, untethered, Quail Bell, The Nashwaak Review, Orbis, Snakeskin Poetry, M58, CV2, Brittle Star, Bombfire, American Mathematical Monthly, The Academy of Heart and Mind, Canadian Woman Studies, The Mathematical Intelligencer, The Canadian Journal of Family and Youth, The Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, The Beatnik Cowboy, Borderless, Literary Veganism, and more. His lit crit has appeared in Ariel, Hamilton Arts and Letters, Episteme, Studies in Social Justice, Rampike, and The /t3mz/ Review. Terry Trowbridge lives in Beamsville, Ontario.

*

Works cited:

Aronson, Arthur, [Media relations]. (30 march, 2022). Historic action plan guides UNDRIP implementation in B.C. Victoria: Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation. Web.

Ballantyne, Hamish. (2020). Imitation Crab. Toronto: Knife/Fork/Book.

Kirby. (29 September, 2022a). I want to send you a box of poetry… Twitter.

Kirby. (10 October, 2022). Been joyously boxing/shipping… Twitter.

Lanham, Richard. (1991). A Handlist of Rhetorical Terms, Second Edition. London: University of California Press.

Lawrence, Michael, Janzwood, Scott, and Homer-Dixon, Thomas. (16 September, 2022). What is a Global Polycrisis? And How is It Different from Systemic Risk? Technical Paper #2022-4, Version 2.0. Royal Roads University: The Cascade Institute.

Lear, Edward. (1992). A Book of Bosh. London: Puffin Books.

Neuhaus, Mareike. (2015). The Decolonizing Poetics of Indigenous Literatures. Regina: University of Regina Press.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

6 comments on “1718 The rhetoric of Imitation Crab”