1710 Mynett’s Skeena stories

River of Mists: People of the Upper Skeena, 1821-1930

by Geoff Mynett

Qualicum Beach: Caitlin Press, 2022

$26.00 / 9781773860930

Reviewed by Tyler McCreary

*

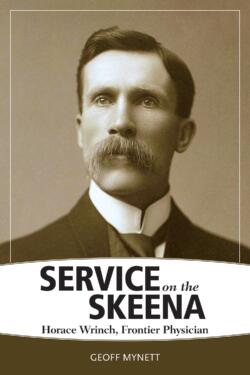

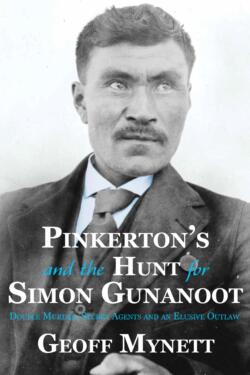

Geoff Mynett has quickly emerged as the leading public historian of the Upper Skeena region of British Columbia. A remarkably proficient and prodigious author, he has now published his fourth book on Hazelton history in the last two years. With each text, he has taken a different tack: first, biography in Service on the Skeena, recounting the story of missionary doctor Horace Wrinch; then, nonfiction detective in Pinkerton’s and the Hunt for Simon Gunanoot, following two private investigators along their failed search for an Indigenous outlaw; third, true crime in Murders on the Skeena, describing the conflict of Gitxsan and settler laws that arose around a series of turn-of-the-century murders. In his most recent book, Rivers of Mist: People of the Upper Skeena, 1821-1930, he uses a series of biographical vignettes to create an account of more than a century of development in the region.

Geoff Mynett has quickly emerged as the leading public historian of the Upper Skeena region of British Columbia. A remarkably proficient and prodigious author, he has now published his fourth book on Hazelton history in the last two years. With each text, he has taken a different tack: first, biography in Service on the Skeena, recounting the story of missionary doctor Horace Wrinch; then, nonfiction detective in Pinkerton’s and the Hunt for Simon Gunanoot, following two private investigators along their failed search for an Indigenous outlaw; third, true crime in Murders on the Skeena, describing the conflict of Gitxsan and settler laws that arose around a series of turn-of-the-century murders. In his most recent book, Rivers of Mist: People of the Upper Skeena, 1821-1930, he uses a series of biographical vignettes to create an account of more than a century of development in the region.

In a series of short entries, he provides captivating episodes from the lives of several dozen frontiersmen. Mynett’s selection foregrounds the narratives of a few dozen newcomers to Gitxsan territories, including explorers, traders, miners, missionaries, policemen, and government agents. The figures he features are overwhelmingly male, reflecting the preponderance of men among the white population on the frontier. Mynett does note the few white women that appear on the historical record, typically frontier wives and nurses as well as the occasional tourist.

Mynett does not include any Indigenous people in his catalogue of historical personae in the region. Despite the numerical predominance of Indigenous people in the region at the turn of the century, none of the historical actors that Mynett describes are members of the local Gitxsan community, or the neighbouring Witsuwit’en (Wet’suwet’en), Nedut’en (Babine), or Tse’khene (Sekani) nations. In the preface, Mynett acknowledges this limitation, disclaiming personal capacity to speak to Indigenous history and instead directing readers to Neil Sterritt’s book, Mapping My Way Home. The problem here is that it assumes that Gitxsan history is separable from white history, and that one can make a meaningfully account of local developments without attending to Indigenous contributions. The effect is that the Indigenous inhabitants of the region appear as a backdrop for the historical unfolding of white settlement and conflicts between different colonial authorities. They are disappeared as historical actors on their own lands. In River of Mists, this gap seems particularly galling as the chosen title is a translation of ‘Ksan, the Gitxsan name for the Skeena River.

Nevertheless, Mynett never claims to present a complete regional history, and indeed notes that his is a partial and episodic account of local history, featuring some significant figures and moments, but also more than a few irreverent ones. The first chapters of the book focus on the early efforts to map the Upper Skeena, building trade links and communication infrastructure to traverse the space. This begins with Hudson’s Bay Company traders William Brown and Simon McGillivray, who sought to expand their commercial activities in the Skeena watershed in the 1820s and 1830s, mapping the network of Indigenous trails and rivers across the region. Then in the 1860s, the Western Union Russian-American Telegraph sought to build communication infrastructure across Gitxsan territories. Although the telegraph project was ultimately abandoned, it extended a new path connecting settlers from the south to the region.

The second part of River of Mists details the period from the 1870s through the turn of the century, focusing on the community of prospectors who came seeking gold in the Omineca. Here Mynett focuses on the various itinerants and occasional settlers to the region who came as prospectors, retelling the foibles of miners such as Jim May or Jack Gillis. Although Mynett ostensibly focuses on particular figures, his account effectively captures how the natural and social environment of the north impacted early placer miners’ experiences. The stories he tells do not simply celebrate the bluster of gold-seeking newcomers; River of Mists details the extent to which these prospectors remained vulnerable to the vagaries of the rivers and wilds through which they travelled. They also depended on the expansion of trade and transportation infrastructure associated with the community of Hazelton. Thomas Hankin, the founder of Hazelton, was a former fur trader who reoriented his commercial enterprise to provision prospectors. Edgar Dewdney, the provincial surveyor, is also historically significant to the region, despite the brevity of his stay, as he built on the old Western Union route to map the trail to the Omineca.

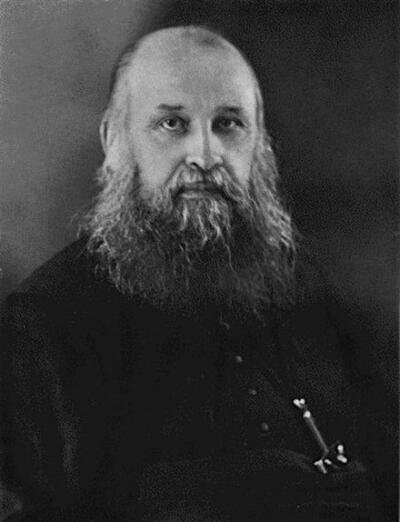

In the middle of the book, Mynett turns his focus to the various figures that sought to secure spiritual and physical well-being, as well as law and order, in the Upper Skeena. He introduces missionaries Anglican Bishop William Ridley and Catholic Father Adrien-Gabriel Morice, following the weave of their epistolary threads. While the missionary enterprise aimed to capture Indigenous souls for Christianity, church records provide a poor account of how Indigenous people understood this encounter. Instead, missionary missives and journals reflect their own aspirations and anxieties as colonial agents of evangelism. Mynett’s account reads along the archival grain of colonial concerns often removed from the lives of their would-be wards. Ridley is foiled against his Anglican competitor, the maverick missionary William Duncan, who has abandoned administering the practice of communion to his flock of Tsimshian converts. Morice appears, unsympathetically, to be a paternalistic pedant intent on exploiting his followers to advance his intellectual standing as a linguist, historian, and ethnographer. Mynett is more sympathetic to the motivations of medical missionary Horace Wrinch, as well as the women who assisted him as nurses in the Hazelton hospital.

River of Mists also presents the struggle over law and order in predominantly moral terms, largely centred around crimes of vice — bootlegging and prostitution. Mynett’s narrative here is an ambivalent one. On the one hand, he portrays sympathetic accounts of early lawmen James Kirby, Sperry Cline, and James Maitland-Dougall, who sought to bring order to the frontier. On the other hand, he highlights recurrent concern with profligate vice in the region and the seeming indifference of certain civic leaders in containing it. The illegal liquor trade was a particular locus of concern for authorities, both in terms of the unlicensed saloons and prohibited sale of alcohol to status Indians in the period. However, as Mynett notes, certain elements of settler society continued these illicit activities, as well as frequenting the homes of sex workers. Mynett describes a particularly instructive feud between the local Indian agent Richard Loring and businessman and provincial magistrate Richard Sargent. Loring wanted to restrict the illicit sale of liquor to Indigenous people, and he believed that Sargent both engaged in such sales and blocked the application of legal punishments for this activity. Loring, however, never succeeded in forcing Sargent from his position in the community.

The final section of the book, which carries the narrative through the First World War and to the Depression, is more scattered. In one of the few chapters centring a female character, Mynett describes the role of trips to the Upper Skeena to the development of Emily Carr’s art. He then details the Great War experiences of men and women from Hazelton. The collection concludes rather oddly with anecdotes about the first airplane visit and political automotive caravan, respectively in 1920 and 1930. Both events were associated with campaigns to extend transportation infrastructure to more effectively link Alaska thru Canada to the continental United States; however, these projects were stillborn in the period with regional airport and highway developments waiting years.

These final chapters skip over the biggest development that would reshape the region—the creation of the railway. While travel in the region had previously relied on trails and rivers, Hazelton was a vital node at the Forks of the Skeena and Bulkley rivers. However, the arrival of the railway reoriented the flow of goods and people. New centres emerged in the region and the scale of extractive development multiplied, antiquating Old Hazelton and its community of small placer miners.

Ultimately, Mynett’s biographical vignettes are most compelling in the period before these transformations. In the stories of the early explorers and missionaries, prospectors and police, he captures the slow unfolding of the first century of colonialism on Gitxsan land. However, Mynett only tracks the white history of this process. It is thus necessary to read his book alongside others, such as by Sterritt, to attend to the impacts of these developments for the Gitxsan and other Indigenous peoples, as well as to recognize the ways in which Indigenous peoples have negotiated, resisted, and modified these changes.

*

Born and raised in Northwestern British Columbia, Tyler McCreary is an assistant professor of Geography at Florida State University, and an adjunct professor of First Nations Studies at University of Northern British Columbia. His research examines how Indigenous-settler relations configure the politics of land, labour, and community life. He has analyzed how environmental governance processes address Indigenous relationships to the land, how Indigenous peoples interact with resource sector labour markets, and how processes of urban and regional governance impact Indigenous families living in towns and cities. He has published over three dozen scholarly articles and book chapters as well as (with Mary Lawhon) Enough!: A Modest Political Ecology for an Uncertain World (Newcastle upon Tyne: Agenda Publishing, forthcoming May 2023), and Indigenous Legalities, Pipeline Viscosities: Colonial Extractivism and Wet’suwet’en Resistance (University of Alberta Press, forthcoming January 2024). Previously, he coedited (with Heather Dorries, Robert Henry, David Hugill, & Julie Tomiak) Settler City Limits: Indigenous Resurgence and Colonial Violence in the Urban Prairie West (University of Manitoba Press, 2019). His first book, Shared Histories: Witsuwit’en-Settler Relations in Smithers, British Columbia, 1913-1973 (Creekstone Press, 2018), which is reviewed here by Keith Smith, won the BC Historical Federation’s Lieutenant Governor’s Medal for Historical Writing for best book published in 2018. Editor’s note: Tyler McCreary has also reviewed two previous books by Geoff Mynett, Gunanoot and Horace Wrinch, as well as books by Robert Budd & Roy Henry Vickers and Keith Thor Carlson et al. for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster