1702 Fragments of grief & mourning

Holden After and Before: Love Letter for a Son Lost to Overdose

by Tara McGuire

Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2022

$24.95 / 9781551528939

Reviewed by Colin James Sanders

*

Human beings, not unlike other creatures, contend with the death of loved ones, navigating grief and mourning in varying ways. Tara McGuire of Vancouver channeled her mourning into an homage to her son Holden, who died of a toxic mix of heroin and alcohol in 2015, aged twenty-one. McGuire’s Holden After and Before: Love Letter for a Son Lost to Overdose presents a poignant and poetic portrait of a young, creative, conscientious son with a sense of social justice who sought to manage his struggles and dilemmas with substance use.

Human beings, not unlike other creatures, contend with the death of loved ones, navigating grief and mourning in varying ways. Tara McGuire of Vancouver channeled her mourning into an homage to her son Holden, who died of a toxic mix of heroin and alcohol in 2015, aged twenty-one. McGuire’s Holden After and Before: Love Letter for a Son Lost to Overdose presents a poignant and poetic portrait of a young, creative, conscientious son with a sense of social justice who sought to manage his struggles and dilemmas with substance use.

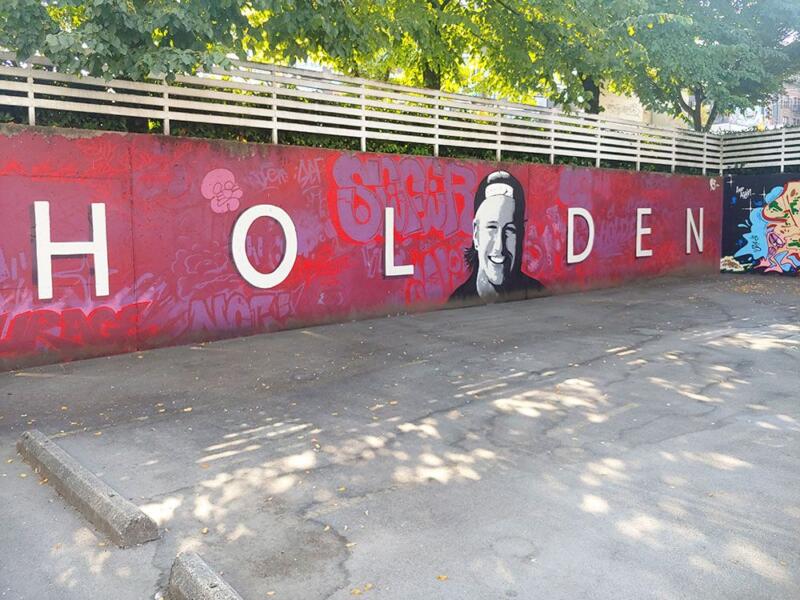

“Holden had the soul of an artist,” McGuire writes. “He was naturally poetic and imaginative” (p. 363). He found meaning in the anarchy of creating street art and, on the basis of a portfolio of photographs of his graffiti, charcoal drawings, and a painting of Bill Murray, he was accepted into the Emily Carr School of Art and Design, which he attended for about one year. On a trip with his mother to New York celebrating his sixteenth birthday Holden tagged the Brooklyn Bridge: that is, he spray-painted his name on it.

Holden could play guitar and piano and, at an early age, “… began to create what we now think of as graphic novels. He called them comix, with an x…” (p. 364). McGuire writes that Holden’s collection of books included “Kerouac, Hemingway, Burroughs, Wolfe, Thompson — the classic list of the disillusioned adolescent” (p. 102). His favourite poem was Beat poet Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl”, which begins, “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by / madness, starving hysterical naked, / dragging themselves through the negro streets at / dawn looking for an angry fix….”

Holden was aware of literature in ways his acquaintances were not. At a party, he asked a young man, “Hey, you like Kerouac?” to which the fellow responded, “I haven’t heard any of their songs … are they any good?” (p. 109).

McGuire writes about emotionally rereading while pregnant The Catcher in the Rye (1951), J.D. Salinger’s controversial novel about teenager Holden Caulfield. On the trip McGuire made to New York with Holden, they visited together The Dakota Apartments, where John Lennon was murdered by Mark Chapman who, when arrested, was holding a copy of The Catcher in the Rye.

McGuire informs the reader that when expecting the birth of her son, she had decided, along with Holden’s biological father, to name the child Holden after his paternal grandmother:

I began to worry that choosing the name Holden might be a mistake. It weighed too much. Anyone who had read the book — which was basically anyone who attended high school in North America — would envision a delusional teenager in a hunting cap at the mention of the name. The kid in the book was just too sad and confused. Lovable, smart, and funny, yes, but also becoming mentally unhinged and largely oblivious to it (p. 101).

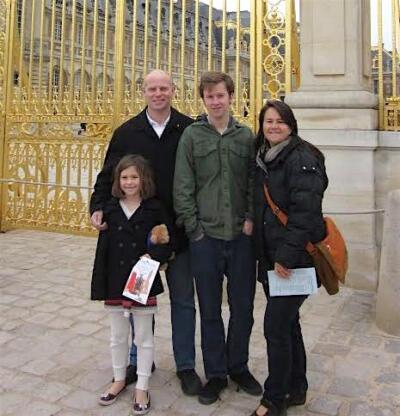

On what turned out to be the final year of Holden’s life, McGuire, her husband Cam, and their daughter Lyla were travelling in Europe. In retrospect, following Holden’s death, McGuire ruminates, “During the dark empty hours, all I could see what the lighthouse of my mistakes flashing error, error, error. I relived every parental wrong I had committed…. But the biggest one was the hardest to bear. I would never forgive myself for missing the last year of his life” (p. 122). “Retrospect is a devastating vantage point” (p. 190).

In writing her love letter to her son, McGuire observes that “I was a private eye building a case with rudimentary forensic investigation skills” (p. 76) in her adroit and articulate reconstruction of Holden’s final year. “I used these fragments and intermittent whispers as wood and nails to construct conversations, to erect whole situations. Holden was resuscitated in the scenarios I built in my mind….” (p. 81). To make sense of a senseless death, McGuire imaginatively reconstructs events leading to Holden’s demise. The fragments and whispers are many, including emails received from Holden and collateral information and anecdotes from conversations with others, including Holden’s physician, the psychotherapist he reluctantly saw and never connected with, the Chief of the Vancouver Police Department, a psychic Holden consulted, and conversations McGuire arranged with Holden’s close friends.

Holden “was often depressed and anxious,” she writes. “He was often optimistic and philosophical” (p. 77). “My son was an enigma” (p. 366). McGuire believed Holden was using substances in an attempt to “settle his soul” (p. 232). What becomes clear is that Holden was thinking of making changes within his life, particularly in regard to substance use, not long before his death.

Perhaps what is important is that Holden thought of making these changes, imagining a radically different way of being in this challenging world. I wonder if he was too sensitive for this world. McGuire tells the reader about finding this confession of Holden’s written on the computer in their home, the page open for her to discover: “Lately I have been feeling an uncontrollable sadness. I don’t know what is causing this. But I feel lonely and insecure. The need to be around people I like is gone. Sometimes I feel that I am the only human being on earth” (p. 48).

Holden’s narrative, while intrinsically unique and extremely personal to McGuire, exists within a context shared by all too many others. In British Columbia, by 2016 it was estimated that 68 percent of 985 illicit drug poisoning deaths involved fentanyl.[1] The fentanyl-contaminated drug supply has evolved since that time in an increasingly destructive way. “At least 1,095 British Columbians are believed to have been lost to the toxic drug supply between January and June 2022, according to preliminary data released by the B.C. Coroner’s Service.” This same provincial government news release observed that, “Illicit drug toxicity is the leading cause of unnatural death in British Columbia and is second only to cancers in terms of years of life lost.” The release further observes that British Columbia “…has now lost more than 10,000 lives to illicit drugs since April 2016.”[2]

It has been estimated that six persons die daily in Vancouver from opioid toxicity-related overdoses. Recently, BC’s NDP Premier David Eby announced policy initiatives intended to further expand mental health support teams and enhance services for persons struggling with mental health and wellness dilemmas coupled with substance use.[3] With this announcement, I found myself holding hope and despair simultaneously: hope that more progressive harm-reduction changes might continue to be implemented in BC, and despair for the lives already lost. Needless to say, despite its moving content and many fine literary qualities, I would be relieved to never again have to read an account such as Tara McGuire’s Holden After and Before: Love Letter for a Son Lost to Overdose.

“He thought a lot about his place in this world, his meaning, what his life was about, which, as you know, can be a very confusing topic. Sometimes I think he just didn’t know where to put all of his thoughts and feelings. They were heavy for him to carry” (p. 366). McGuire’s heartfelt remembering of her son bears witness to his brief life, in all of its contradictions, all of his struggles, and all of his triumphs and accomplishments. “Though he is gone, he is not going away…” (p. 7).

This often heart-breaking narrative will ensure that Holden will be remembered and will live within the minds and hearts of those who knew him as a friend, and the others who dearly loved him.

*

Colin James Sanders, PhD, husband, father, grandfather, lives with his partner Gail and their creature companions on the unceded traditional lands and waters of the Skwxwú7mesh Úxwumixw and the shíshálh Nation on BC’s Sunshine Coast. Amongst his professional accomplishments, Colin co-created a live-in program for young persons struggling with substance use and was a professor from 1998-2018, and a Director of the Master of Counselling Programs, at City University of Seattle’s Vancouver campus. Colin has presented his work throughout Canada and in San Francisco and Havana. Colin has published academic book chapters and journal articles relating to his therapeutic practice over the decades, in addition to book reviews, interviews, and essays on poetry and poetics. Colin is a member of the Editorial Board of The GTEC Reader, an online journal of Vancouver’s Green Technology Education Centre. Recent publications include a two-part essay on the climate crisis and eco-socialism; a poem illustrated by several of his paintings and a memoir recalling his therapeutic praxis in New Zealand’s online Journal of Contemporary Narrative Therapy. Colin spends his time learning from his grandchildren, reading, writing, painting, and travelling. Editor’s note: Colin Sanders has also reviewed books by Amanda Siebert and Keith Warrior for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] Lisa Belzek & Jessica Halverson, Evidence synthesis: The opioid crisis in Canada: a national perspective. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: Research, Policy and Practice. Vol 38, No 6, June 2018

[2] BC Gov News Release, August 16, 2022

[3] See https://strongerbc.gov.bc.ca/safer-communities