1637 Time regained

The Lost Century

by Larissa Lai

Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2022

$24.95 / 9781551528977

Reviewed by Hanako Masutani

*

“Don’t you read your history books!” Violet Mah, a retired medical doctor and part-time narrator of The Lost Century, berates her niece, a proxy for the reader. Larissa Lai’s latest novel opens in a hole-in-the-wall restaurant on June 30, 1997, Hong Kong’s last day as a British crown colony. To commemorate the occasion, Violet’s niece has begged her aunt to spill the gory details of their family history. Begrudgingly, Violet obliges, packing what she can of a century into the hours spent eating a sumptuous meal. If you are anything like me, in the niece’s shoes, you will drool over the food and confess, no, you have not read your history books, at least, not the ones that aren’t written by the victors. Disguised as the narrative of an extended family made up of the Mahs, Cheungs, and Lees, The Lost Century is an education. Never have I felt so squarely situated within world history. For how can we know Vancouver without an inkling of how the Hong Kong Chinese, Indians, British, Indigenous Canadians, and Japanese have been dancing for, oh, the last 100 years?

“Don’t you read your history books!” Violet Mah, a retired medical doctor and part-time narrator of The Lost Century, berates her niece, a proxy for the reader. Larissa Lai’s latest novel opens in a hole-in-the-wall restaurant on June 30, 1997, Hong Kong’s last day as a British crown colony. To commemorate the occasion, Violet’s niece has begged her aunt to spill the gory details of their family history. Begrudgingly, Violet obliges, packing what she can of a century into the hours spent eating a sumptuous meal. If you are anything like me, in the niece’s shoes, you will drool over the food and confess, no, you have not read your history books, at least, not the ones that aren’t written by the victors. Disguised as the narrative of an extended family made up of the Mahs, Cheungs, and Lees, The Lost Century is an education. Never have I felt so squarely situated within world history. For how can we know Vancouver without an inkling of how the Hong Kong Chinese, Indians, British, Indigenous Canadians, and Japanese have been dancing for, oh, the last 100 years?

Larissa Lai has been writing about Asian history through a political lens since at least 2005. She is also an award-winning poet and scholar. Her earlier novels When Fox is a Thousand, Salt Fish Girl, and The Tiger-Flu wield aspects of magical realism and speculative fiction to explore our collective past. The Lost Century is, by contrast, realist and grounded in fact. But the truth, as they say, can be stranger than fiction.

Lai’s Hong Kong of 1941-42 is a dystopic land where different races oppress and murder one another, often for the idea of empire. There are few “good guys” here. Violet explains:

You could be pro-democracy, but the possibility of being pro-democracy without being pro-British and therefore in favour of European colonialism was not yet available. You could be Pan-Asian and anti-colonial, but then you’d find yourself supporting Japanese fascism. You could be a Chinese Nationalist, but the Kuomintang leadership was notoriously corrupt and actively employed Nazi brownshirts to train its own blue shirts. You could be pro-Communist … but look at how many millions of people were murdered by the Communists later in the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution! (p. 210).

Caught in a net of cruel ideologies, The Lost Century’s cast are drug lords, murderers, rapists, addicts, and smugglers, to name a few. It’s a dog-eat-dog world where the body parts of the tortured are carried out in buckets and literally fed to waiting packs of feral hounds.

Within this bleak landscape, Lai is careful not to draw tidy lines between morality and race. The Japanese Kempeitai are responsible for the story’s worst tortures, but even its military officers are spoken of with tenderness as they sleep. They dream “simply of wives, mothers, children, or lovers, and their own natal villages by the sea or in the hills, not so different from the villages they had plundered and torched these last five years” (p. 351). One of the novel’s most likeable characters is also Japanese-Shigeru Tanaka (or Tanaka Shigeru, according to the Japanese custom of putting surnames first, a custom Century preserves), a translator and musician born and raised in Hong Kong. Similarly muddying the waters is the depiction of the local Chinese, some of whom willingly poison their kinsfolk for profit; others hustle their neighbours across borders at the cost of their own lives. Some UK expats are self-indulgent drunks, others kindly professors. The list goes on and on.

The Lost Century showcases not only Lai’s fair-minded and nuanced understanding of geopolitics, but also her considerable writing chops. Certain lines are sharp reminders that Lai is also a poet: “He became a twisted guide to the underworld, a dreadful shepherd, a broken boatman” (p. 351). Other passages read like theatre of the absurd. During a sinister cricket match between the British and the Japanese, both teams filled out by their respective sympathizers, a ball flies:

high over the stands and right over Des Voeux Road. It sailed so straight that it looked like it would smack the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank right in the crack between the left and right sides of the double door, albeit at an interesting angle. Just at that point, a debtor, going in to pay what he owed at Governor Isogai’s order on pain of death pushed both door panels open. The ball sailed into the bank and bopped Teller number 7 in the forehead (pp. 297-98).

If you are looking for happy endings, you will not find them in The Lost Century. If you are looking for Shakespearean tragedy, likewise. Lai takes her brutally realistic story to its mundanely realistic conclusion — loved ones continue to terrorize and wound each other, though quietly. But like all good historical fiction, The Lost Century provides timely commentary on current atrocities appearing on our e-news, YouTube, TikTok, and Twitter radar. Unfortunately, so far, it is always timely to write about race, violence, and power.

*

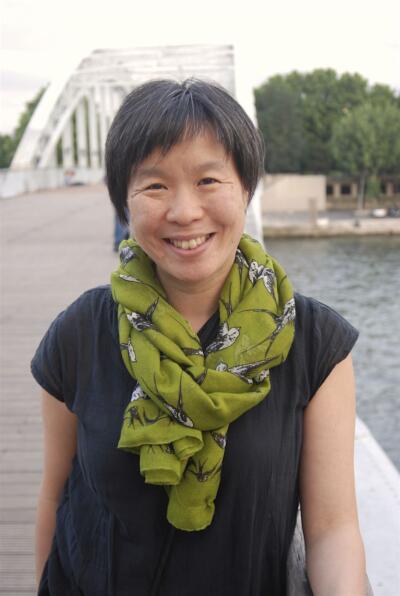

Hanako Masutani is a Vancouver parent, teacher, and writer. Her poem “Charlie Horse” was awarded Arc Poetry Magazine’s Confederation Poets Prize in 2018. Her poems, fiction, and essays can be found in Geist, Grain, The New Quarterly, and Riddle Fence, among other publications. Look for her early reader Emi and Mini, to be published by Tradewind Books in June 2023. Editor’s note: Hanako Masutani has also reviewed a book by Jasmin Kaur for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1637 Time regained”