1632 Expecting full envelopes

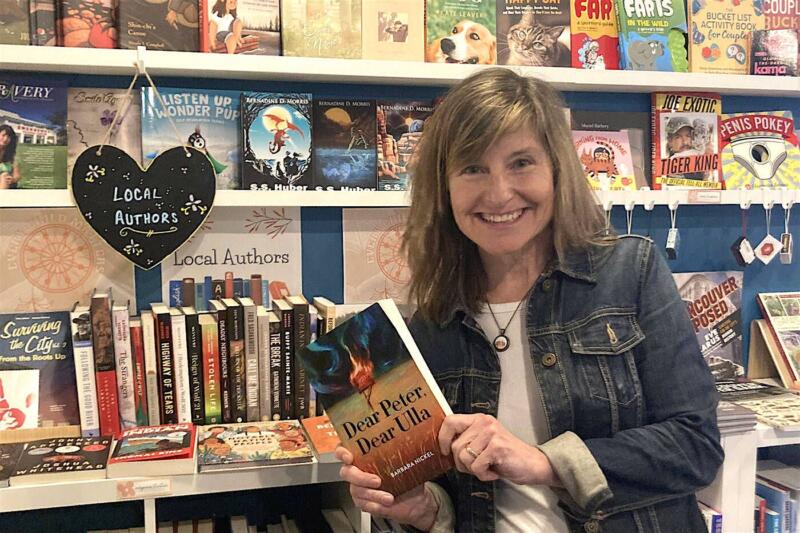

Dear Peter, Dear Ulla

by Barbara Nickel

Saskatoon: Thistledown Press, 2021

$16.95 / 9781771872232

Reviewed by Alison Acheson

*

Barbara Nickel’s Dear Peter, Dear Ulla is a gift. While written for tweens to young teens, many adult readers would enjoy it too. The full cast of characters of all ages are well-developed for their roles, and the blend of epistolary form with narrative creates an insightful and active story.

Barbara Nickel’s Dear Peter, Dear Ulla is a gift. While written for tweens to young teens, many adult readers would enjoy it too. The full cast of characters of all ages are well-developed for their roles, and the blend of epistolary form with narrative creates an insightful and active story.

Just out of the barn door, Peter stumbles and spills the milk. He can’t take his eyes off the sky, huge and strange with something about to happen. He stoops to wipe the bucket’s side and looks up again. There’s a heap of dark clouds like ocean waves, or smoke rolling out of a battleship off to shell the enemy.

This is the opening, and like any strong opening, it foreshadows the end, gives the reader an idea of character, location and — most importantly — the emotional pull. We will learn that Peter is not a young person who cries over spilled milk, even if he feels like it, and that he wipes up and goes on. We learn of his close awareness and connection with the world around him, and how tuned in he is; we learn he cares. It’s no surprise to learn he has a cousin he’s never actually met, yet with whom he exchanges letters and has a great friendship.

Peter is twelve, and his cousin Ulla is the same. Peter lives in a rural Mennonite farming community in Saskatchewan, and Ulla lives in Nazi-occupied Danzig. For years they have been pen pals, but the outbreak of the Second World War brings consistent delivery of their letters to an end.

It does not stop them from writing though, and it does not stop them from living and hoping and learning about the light and shadows of the world around them, and the madness of grownups and other bullies.

In their letters they share their passions: Ulla draws pictures of her world, and Peter works on a piece of music, telling her about it, movement by movement, bringing his farming and winter world to musical life. The sustaining nature of art and music is a strong thread pulled through the story, holding it in place like tent-string pegged to the ground.

Their letters capture their voices with different rhythms and tone. They take the reader to a time when communication was slowed. Even when letters were sent in pre-war years, the back-and-forth would be over a period of weeks. But in this story, the weeks are long. Sometimes three full envelopes turn up at once after months. So different from now, in 2022, when we have the click of a button and passing of seconds to communicate.

But in this story, in communicating, there is anticipation, patience, sharing, thought. When both Ulla and Peter know there’s a chance that their letters might not arrive or be read, they continue to write, even storing away the letters until the time comes to send with certainty that the message will be delivered. There’s wonderful undercurrent in this story-telling, of how we hold those we love in our hearts, and how that holding communicates on an entirely different level. And then there is the reassurance of a timely telegram! A word unfamiliar to so many.

The sacrifices in Ulla’s family, as they support their Polish friends and neighbours, are sizeable. Her father takes a janitorial job when he is removed from his post as a policeman; her mother goes to work in a chocolate factory. They sell the family car. Meanwhile in Canada, Peter must deal with a bully, a boy whose response to the war is to create cruel lines between classmates and friends. And the responses of Peter and Ulla are individual and realistic: Ulla can no longer eat her favourite apple cake — it’s tainted for her. Peter has to re-group to continue creating music. Wounds and healing — and healing well — are significant themes.

Nickel’s research is thorough. When a writer writes historical works, they use at the most ten percent of their research. But the other ninety percent must be done; it becomes a significant part of the place from which they work, all a necessary part of the process. There are no shortcuts. Nickel’s research re-creates the places and the past with just the right notes and details of a fully immersed writer. And her notes and postscripts are rich material: recipes and photos and maps. The care that Barbara Nickel has put into her other historical works is here again (The Mozart Girl, 2019; Hannah Waters and the Daughter of Johann Sebastian Bach, 2006).

The work has now been a finalist and winner for a number of awards, all so deserved: the Sheila A. Egoff (BC Book Prize), the High Plains Book Award, the Geoffrey Bilson Historical Fiction award, and others.

Dear Peter Dear Ulla will fill the reader’s heart and emotional toolbox in the best ways, in the ways literature does. I’ll not use the word “should.” This is not a didactic story. It’s a real and human story, and timeless.

*

Alison Acheson is the author of almost a dozen books for all ages, with the most recent being a memoir of caregiving: Dance Me to the End: Ten Months and Ten Days With ALS (TouchWood, 2019). She writes a newsletter on Substack, The Unschool for Writers, and lives on the East Side of Vancouver. Editor’s note: Alison Acheson has also reviewed a book by Caroline Adderson for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

6 comments on “1632 Expecting full envelopes”