1527 Turbulence and eruption

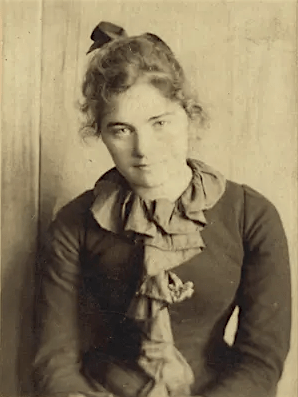

Emily Carr, Unvarnished: Autobiographical Sketches by Emily Carr

by Kathryn Bridge (editor)

Victoria: Royal British Columbia Museum Press, 2021

$24.95 / 9780772679642

Reviewed by Colin Browne

*

Turbulence and Eruption: Emily Carr, Unvarnished

Turbulence and Eruption: Emily Carr, Unvarnished

There’s a scene in Kathryn Bridge’s wonderful collection, Unvarnished: Autobiographical Sketches by Emily Carr, that sticks in my mind. It’s June 1936. Carr, then sixty-four, is camping in “The Elephant” — her van — in the Gravel Pits north of Albert Head near Victoria. She is as enraptured as she would ever be, free to sketch, paint, and write, to gaze deeply into the forest where she encountered traces of the Divine. In an unpublished sketch entitled “In the Van, June 1936,” she describes the early mornings when she ran through the wet grass in her bare feet, swinging her pails and singing, “Oh ye works of the Lord Bless ye the Lord. Praise him and magnify him for ever.” She experienced pure joy. “Life seemed so responsive,” she wrote, “and awefully good. I did up camp cooking over an open camp fire & shouldered my big sketch sack & went off to the woods. In the evenings there were good skies over the sea and pits and when the light was gone & the campfire out the Old Van with the lamp & the hot brick for my feet and my typewriter clicking out the tune of my stories” (p. 126). She didn’t waste a moment. (Please note that the spelling, grammar, and punctuation here have been reproduced as they are in the original manuscript found among Emily Carr’s papers in the BC Archives).

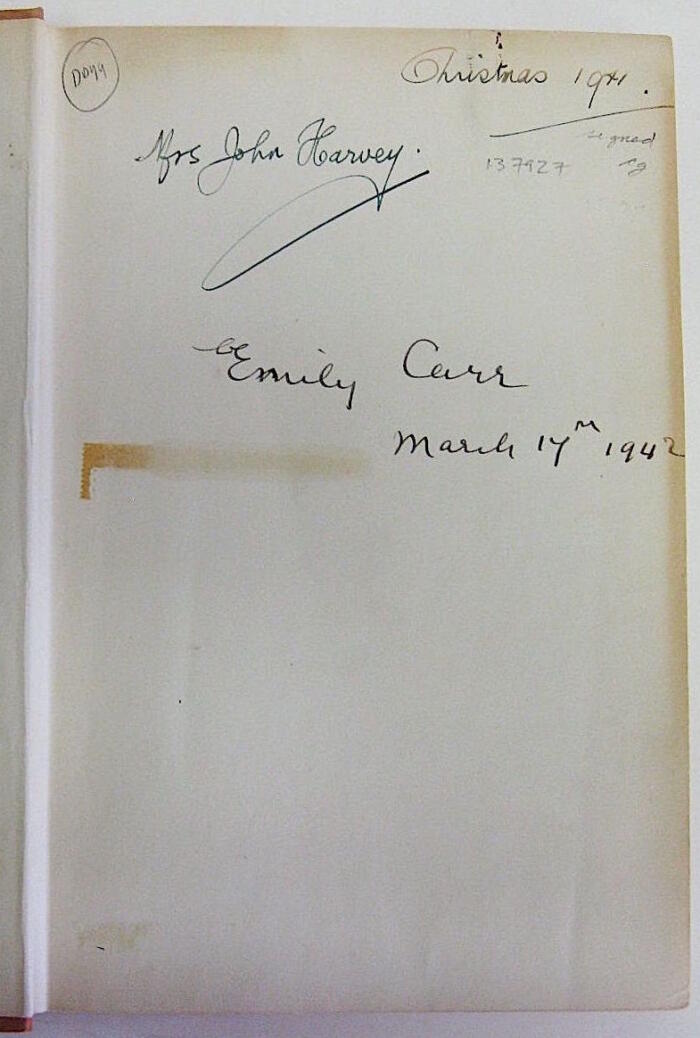

The vision of Carr typing in the glow of a kerosene lamp, surrounded by sleeping dogs, birds, a monkey, and the white rat Susie, reflect her ambition and her ongoing effort to see in a “larger way.” Much of her writing is a conversation with herself, centring on her joys, her frustrations, and her struggles as an artist. “I found writing helped painting,” she wrote, “as painting helped writing. It seemed to make things clearer in my own mind, trying to express them one way or another. It taught me to look deeper with a searching earnestness. I visualized my words and worded my ‘seeings’ and seemed to get a fuller understanding a deeper inlook” (p. 128). Am I right to find a touch of Gerard Manly Hopkins in this phrase? These and many other autobiographical sketches, written out in the pages of two scribblers during the 1930s, make up the larger part of Unvarnished, may be seen as studies or early drafts for her autobiography, Growing Pains: The Autobiography of Emily Carr (1946). They have been arranged chronologically in Unvarnished; one who reads them in order will discover an engaging autobiographical narrative. Those familiar with Growing Pains will be intrigued by the details not included in the published volume.

It’s possible to regard the Unvarnished drafts as a supplement to Carr’s published works, or to consider them of interest only to Carr scholars and aficionados, but they will also serve as a fine introduction to one of Canada’s most significant Modernist artists. The BC Archives hold drawings and sketches by Carr that go back to the 1880s, and, in two inserted signatures of colour plates, Bridge has curated a range of handsomely reproduced images rarely or never seen before. Some are youthful works, comical drawings with funny, awkwardly rhyming poems; political cartoons; and sketches that often poke fun at herself and her sisters.

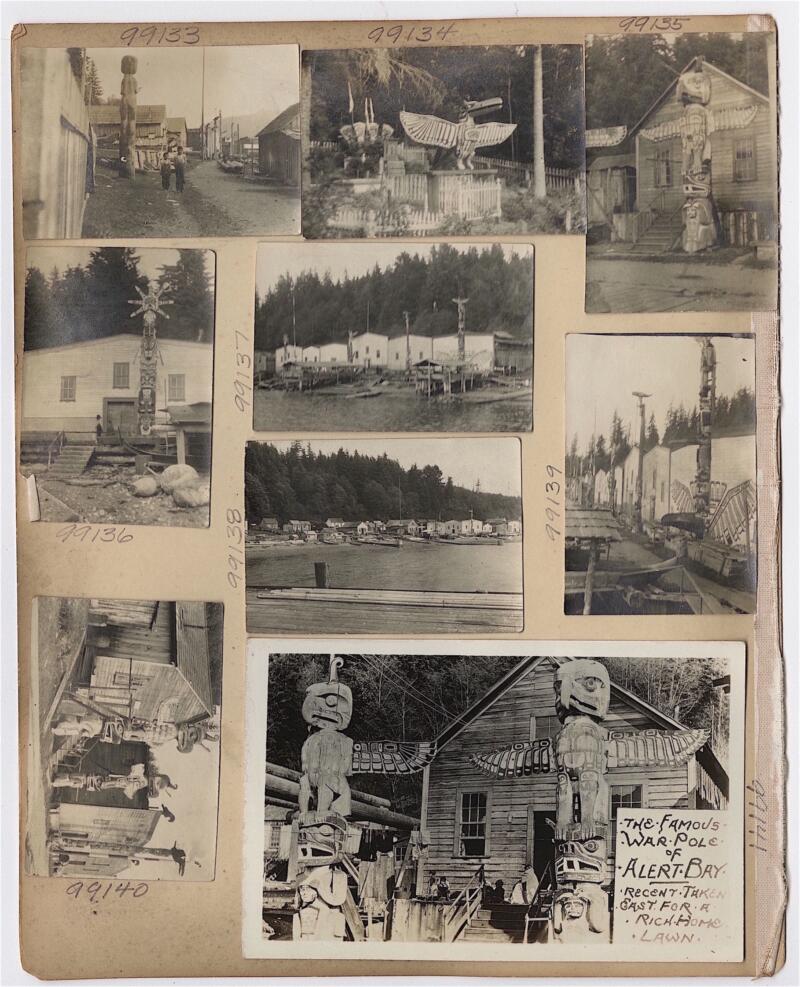

I was drawn also to the pages from her photo album. Some of the snapshots reveal the source of well-known Carr portraits; others concentrate on her beloved pets. As much as she shared her love with them, she also recognized and respected their own instincts and interests. Also included among the colour plates are painted views of Northwest Coast communities, landscapes, and seascapes; and two objects created while supporting herself by making tourist souvenirs with Northwest Coast motifs — a hooked rug and a hand-made pottery lamp and shade decorated with Northwest Coast motifs (1918-1923). Included is a page from her photo album with snapshots of well-known house poles, house frontal poles, and mortuary carvings still standing in ‘Ya̱lis [Alert Bay] during the first two decades of the twentieth century. Carr may have consulted some of these photographs for her paintings.

Unvarnished will be of interest to those who wish to know more about Carr’s sketching and painting in Indigenous villages on Vancouver Island and northern British Columbia. In one entry, recalling her 1908 visit to ‘Ya̱lis, she expresses pride in her ability to paint true likenesses of figures on totem poles:

I boarded with missionaries and worked very hard my drawings were very authentic. I thought, ‘Now this is history & I must be absolutely truthful & exact’ & I worked like a camera. Dr [Charles] Newcombe who was a great authority on Indian stuff came to see my things. He bought three and said would I mind comparing them with his photos of the same poles and possibly adding more detail. ‘The camera can’t take artistic license,’ he added. But when we came to compare there was not a single correction my sketches gave a clearer interpretation than the photographs there was however one bird which lost a wing between the time of his photo & my sketch and this I painted in for him (p. 74) [1]

At the time, most Euro-American settlers, lacking any knowledge of Northwest Coast people, believed that their cultures would soon be lost forever. Carr was one who felt a calling to salvage the standing and fallen posts and poles along the coast by sketching and painting them in situ.

Has any artist in British Columbia written herself into being so insistently, over such a long life, and with such winning guile, as Emily Carr. Her guile was so craftily honed that, invariably, something that has the shape of a deeper truth emerges. The reader may not be surprised to know that she availed herself of mail-order writing courses. Each episode in the scribblers begins with an inviting lede — a strategy reproduced in Klee Wyck and Growing Pains — and is reworked until each takes on a dramatic narrative shape, a model borrowed from magazine journalism. She worked hard to perfect the form, passing the days in hospital while recovering from her two heart attacks in the late 1930s by shaping and editing her autobiographical sketches. It was after her first heart attack in 1937 that she began to record accounts of her visits to Indigenous villages in the North. In her final years she was assisted by her beloved Ira Dilworth who was instrumental in further editing and arranging her work for publication.

Unvarnished reveals a woman who writes compulsively to give shape to her life and the world. She could be unsparing in her criticism of herself. She did not suffer fools, nor did she tolerate disloyalty. She was also a woman who could laugh at herself. And she could be prickly. The artist Lawren Harris believed in her, and provided her with friendship, advice, and support. She describes him in Unvarnished as “calm where I was all turbulence and eruption” (p. 113). During the 1930s, Harris purchased a painting from Carr entitled “Indian Church,” now known as “Church at Yuquot Village.” It remains one of her best-known works. Harris praised it to the skies, too often; Carr lost her cool:

His every letter was full of its praise he spoke as though I had gone as far as I would ever go nothing that I painted after seemed to please him so much as that church. I got angrier every letter he wrote and then I burst out in an angry letter. ‘Stop it! Stop praising that Indian Church. Do you think that is the end of me that I am never to get beyond that beastly little church. Is that picture my limit that you compare everything else I do with it!’ The Indian Church became taboo between us (p. 110).

Those already familiar with Carr’s writing may find themselves pulling out copies of Klee Wyck and Growing Pains to compare with the accounts in Unvarnished. Familiar scenes from her autobiography are now amplified by added details. For anyone interested in her editing process, and the influence of external editors, a comparison of Unvarnished to the other autobiographical volumes offers a window into that process. Kathryn Bridge has provided a superb Preface and an Introduction that explains her editorial approach. If you have read this far, you’ll know already that Bridge has taken pains to make sure that the text remains as true as possible to Carr’s typed and handwritten drafts. Many of the sentences run on without punctuation, some caps and spellings are eccentric, and many references benefit from the endnotes with which the book is so richly endowed. Reading the endnotes alone is an education in Emily Carr’s engaged and complicated life.

Possessed by a strong will and the determination to achieve what she knew she was capable of, Carr spent much of her adult life trying to make ends meet. Misunderstood by her family and the general public, and at the mercy of the constitution she was born with, she was physically susceptible to exhaustion and illness. Her life as a single woman was at times difficult and never far from her mind. Returning to Canada from England in 1904 after spending fifteen months in a sanatorium, she expressed her disappointment with the British approach to art. More distressing for having been bottled up inside was her painful decision to reject the love of a young man who’d travelled to England to propose. (He subsequently lost his life during the First World War). In the sanatorium, doctors encouraged her not to paint or think about art. She was to relax. “Suddenly,” she recalled, “I was aware that the fierce love struggle that had gone on in me for years was dead. I had strangled it after hopeless struggle at last and was glad. While I lay in the sanitorium I had said die, die, die, and at last it had died. It had safeguarded me from many lesser loves & made me suffer furiously. I rejoiced that it was dead at last. But my work the deadness of that was a different manner that must wake again” (p. 65). She was in her mid-thirties.

The final moving entries were written while Carr was a patient in the Royal Jubilee Hospital in Victoria gazing out at Garry oaks. Even these texts were polished through several drafts. Along with the “Introduction,” Kathryn Bridge’s Chronology, endnotes, and Index are thoughtful and generous, equally welcoming to the curious reader and the scholar. The entries in Unvarnished reveal Emily Carr as a seeker, and a scribe, recalling her delights, her despairs, her self-critiques, her self-inventions, her rhapsodic apprehension of the Divine, her love for animals, and the emotionally demanding friendships that left her elated or disappointed. She was as hard on herself as she was on others. In these autobiographical sketches I was reminded of the blissful happiness she experienced when she was living in nature. She sought solace in the forest, in the play of light on new pine needles, and was joyful when she finally solved a painting. Kathryn Bridge has done us all a great service, bringing a more fully realized Emily Carr to life; here she is, unvarnished and alive.

*

Colin Browne is a writer, documentary filmmaker, and academic. His documentary film White Lake (1990) was a Genie Award nominee for Best Feature Length Documentary and his poetry collection Ground Water (2002) was shortlisted for a Governor General’s Award. A longtime professor of film at Simon Fraser University, he co-launched the PRAXIS screenwriting workshop and has been active in efforts to identify and preserve early British Columbia cinema. Other films have included Strathyre (1979), Hoppy: A Portrait of Elisabeth Hopkins (1984), The Image Before Us (1986), Father and Son (1992), and Linton Garner: I Never Said Goodbye (2003). He has been twice nominated for the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize, receiving nods for Ground Water (2003) and The Properties (2013). His most recent collection of poetry is Here (2020). Browne has recently been looking into the surrealist fascination with Northwest Coast cultures; a book is forthcoming from Talonbooks about the surrealist artists who journeyed to the Northwest Coast in 1938 and 1939. His collaborations with composer Alfredo Santa Ana include “Music for a Night in May” (2018) and “Aves, The Four-Chambered Heart” (2023). Editor’s note: Colin Browne’s book Entering Time: The Fungus Man Platters of Charles Edenshaw (2016) was reviewed by Alan Hoover, and the exhibition catalogue, “I Had an Interesting French Artist to See Me This Summer”: Emily Carr and Wolfgang Paalen in British Columbia (2016), was reviewed by Elisabeth Otto for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] Carr sketched and painted in ‘Ya̱lis in 1908 and 1912. She did not meet Newcombe until 1913. He’d have purchased the three paintings at Carr’s studio sale in Victoria in 1913.

One comment on “1527 Turbulence and eruption”

A much needed book and such a splendid review, Kathryn ever in fine fettle as a writer.