1513 History matters: Meares Island

Possessing Meares Island: A Historian’s Journey into the Past of Clayoquot Sound

by Barry Gough

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2021

$26.95 / 9781550179576

Reviewed by Jason M. Colby

*

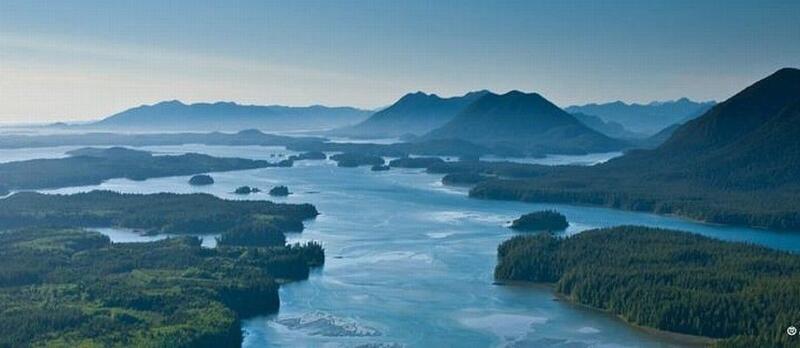

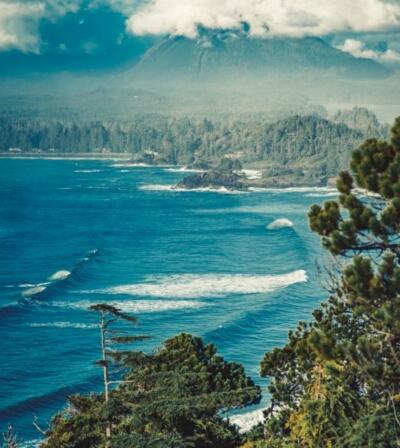

Barry Gough opens his newest book with a phone call that he received in early 1986. On the other end of the line was Jack Woodward, a BC lawyer who was looking for a historian. Specifically, he needed an expert to write a historical report to defend Indigenous title to Meares Island in Clayoquot Sound against a provincial logging license held by MacMillan Bloedel. At stake was not only the survival of some of the most extraordinary old growth trees in North America but also a rising tide of native land claims and litigation that were reshaping the way Canadians understood their nation-state and its history.

Barry Gough opens his newest book with a phone call that he received in early 1986. On the other end of the line was Jack Woodward, a BC lawyer who was looking for a historian. Specifically, he needed an expert to write a historical report to defend Indigenous title to Meares Island in Clayoquot Sound against a provincial logging license held by MacMillan Bloedel. At stake was not only the survival of some of the most extraordinary old growth trees in North America but also a rising tide of native land claims and litigation that were reshaping the way Canadians understood their nation-state and its history.

As always, Gough is a genial and learned guide through the twists and turns of Pacific Coast history. He organizes his story into two parts. The first, “The Empire of Fortune,” accounts for the vast majority of the book, and its tone and content will be familiar to readers of his other work. In it, he offers a deep dive into the events that transformed the coast in the two centuries preceding the Clayoquot crisis of the 1980s.

From the outset, he aims to set readers’ expectations properly. “I have not attempted a social history of the Nuu-chah-nulth peoples over two centuries,” cautions Gough. “This is a book about property and possession” (p. 4). Nevertheless, he gives careful attention to the experience of Indigenous peoples, emphasizing their relationships to land and sea and teasing out their nuanced interactions with Europeans. In doing so, Gough wrestles with the asymmetry of source material that inevitably results from an encounter between an oral culture and a literary culture. Put simply, non-native explorers and settlers tended to leave the written documents that historians have traditionally considered their “primary” sources, thereby privileging European accounts and perspectives. “Of all the challenges the historian faces, this is the most formidable,” he admits. “And so it is with this book” (p. 7).

Nevertheless, Gough manages to convey a superb sense of context and contingency, revealing the complex agency of First Peoples that is often at odds with today’s hindsight. “Empire was not thrust upon them; they invited it,” Gough asserts. “Of course, they could not imagine the future” (p. 41). Likewise, in writing of the Indigenous role in the sea otter trade, he notes that “They richly fed the international economy, particularly the transoceanic link to China, and they entered the global economy without objection and with some enthusiasm, thus aiding and abetting globalization. They were not victims; they were participants” (p. 124).

Throughout the first section, Gough lives up to his reputation as a thorough researcher and careful historian. I frequently found myself marvelling at his command of both broader historical trends and fine-grained detail. Indeed, the only factual errors I found were in his description of grey whales wintering in the Gulf of California and feeding on Arctic krill (p. 53). (The vast majority winter in Baja California’s Pacific-facing lagoons and feed on benthic copepods in the Bering and Chukchi Seas).

Gough’s account is richer in maritime than in Indigenous history, to be sure, and there are moments when his phrasing seems to mimic the diction of non-native sources too closely. At times, this can be innocuous and even charming, such as when he describes characters as “raw-boned” or “well-moneyed” (p. 153). But in other passages, it results in language that demands further analysis. In depicting American expectations on the coast, for example, he writes, “Fresh in their minds was the violence on the coast north of Cape Mendocino, where in August 1788 they had met canoes of fierce and warlike bands addicted to thieving” (p. 97). Likewise, when describing Alexander McKay, Gough notes that “he had been Alex Mackenzie’s right-hand man in that epic 1793 westward passage, and he knew what was described at the time as ‘Indian character’” (p. 114). Yet he leaves these problematic phrases unexamined.

In addition, despite Gough’s careful attention to contingency, there are also passages that seem to hint that history itself was the product of European agency. Of the decades during which European ships bypassed Vancouver Island’s West Coast, for example, Gough writes that “history had passed the place by” (p. 129). Of the British effort to chart the coast and inner waters, he observes, “The navy’s survey of Clayoquot Sound stands at the gate of history: the ancient giving way to the modern, the Aboriginal world view to that of Western science” (p. 155).

The second section, “War for the Woods,” is much shorter, but also rather unique. In it, Gough tracks the history of modern logging on the BC coast, as well as the political and legal struggle over the fate of Meares Island, all the while interspersing bits of reportage and glimpses of his experiences as a member of the legal team. This includes insights on his own research and reflections. “The more I thought about it, the more I saw that British Columbia was an empire by default,” he notes. “The British acquired sovereignty to this great expanse of land out of necessity, not desire. They wanted to keep other nations out” (p. 167).

At times, one can descry the proud Canadian as historian. “Vancouver Island may be seen as a reluctant empire,” Gough writes. “On reflection, it is a phenomenal development—and its legacy was Canada’s window on the Pacific” (p. 167). In a similar vein, he argues that native peoples would have fared much worse under US rule. “In that case, the Indigenous peoples would not be protected under law by what is known as the fiduciary obligation that Canada, by court ruling, is bound to observe” (p. 168). In the same spirit, he asserts that “British — that is, HBC — pressures on the Indigenous peoples were benign in comparison to what was happening in adjacent American western frontiers” (p. 169).

All of these points are debatable. After all, some aspects of colonial control in Canada, such as residential schools, had much shorter lives south of the border. Likewise, the treaties Indigenous nations signed with the US government have given them recourse to federal courts that Canadian First Nations without treaties often lack. Still, there is no denying that the scale of violence and removal in the United States dwarfed that of BC.

In tracking the consistent Indigenous presence on and control of Meares Island, Gough is just as successful in this book as he was in his report for the legal team. And he does an exemplary job of showing how the case both reflected and contributed to changing the balance between federal and provincial views of native rights in Canada. “British Columbia became the key battleground by virtue of the fact that the Government of British Columbia had so long denied Aboriginal title (whereas Canada, following British policy, had always recognized Aboriginal titles and rights)” (p. 195).

In the final analysis, however, it often feels like Gough is wrestling with the same dilemma that has routinely confronted First Peoples and their allies: in order to meet the colonial state’s legal standards for claiming sovereignty (continuous occupation) or existing as a distinct people, Indigenous peoples have to show that colonialism failed to extinguish native title and identity — in this case, never displacing or removing them from Meares Island. The unspoken paradox is that this logic penalizes Indigenous peoples who were historically the target of systematic violence and removal while rewarding those who benefited from benign neglect.

In all of this, Gough pulls back the curtain on the practice and social relevance of history in a way we haven’t seen him do before. The results are revealing and often inspiring. And if the organization and approach of the book are somewhat uneven, Gough has grasped for and revealed a deeper truth that many in our field struggle to articulate: history matters a great deal in the ongoing battles to make the world a better place. Indeed, there is scarcely a political, social, environmental, or policy debate out there that is not, to some degree, framed historically. As such, more historians need to understand the stakes and the importance of sharing their expertise with the public.

As a younger scholar trained in a different time, I may have quibbles with some of Gough’s language or interpretations. I might wish he had integrated environmental and imperial history a bit more, in the model of David Igler’s The Great Ocean (2013), or engaged more directly with Indigenous memory and narrative, in the spirit of Joshua Reid’s The Sea Is My Country (2015).[1] But in many ways, such criticism misses the significance of Gough’s work. In 1986 (when I was still in middle school), Barry Gough learned of the threat to Meares Island and the stakes for Indigenous rights, and he answered the call. Over the following years, he marshalled all of his knowledge, research skills, and intuition as a historian to help save Meares Island and secure Indigenous title. That is the big picture, and he deserves our thanks.

The fight isn’t over, Gough cautions. The extractive and colonial project to log Meares Island remains and could still resume. On this note, I think it is best to give Gough the final word. “Yes, it appears to be First Nations land. But let’s make this clear: it is nonetheless tied up in the red tape of history and regulation, both federal and provincial. It may be a Tribal Park — for which this historian will be eternally grateful — but it is also possessed by the historical tentacles of empire. Empires are based on power, and those powers are seldom relinquished, seldom lapse” (p. 203).

*

Jason M. Colby is chair of the History Department at the University of Victoria and professor of environmental and international history. His most recent book is Orca: How We Came to Know and Love the Ocean’s Greatest Predator (Oxford University Press, 2018). He is currently completing a book entitled Devilfish: The History and Future of Gray Whales and People. Editor’s note: Jason Colby’s Orca: How We Came to Know and Love the Ocean’s Greatest Predator was reviewed by Anna Hall for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] David Igler, The Great Ocean: Pacific Worlds from Captain Cook to the Gold Rush (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013; Joshua L. Reid, The Sea Is My Country: The Maritime World of the Makahs (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015).