1429 A fine Edwardian melodrama

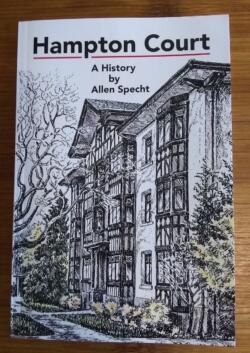

Hampton Court: A History

by Allen Specht

Victoria: Privately Published, 2021

$15.00 / 9781778350450

Available at Books & Shenanigans (347 Cook Street) and Ivy’s Bookshop on Oak Bay Avenue, Victoria, or by contacting the author at <awspecht2@gmail.com>

Reviewed by Martin Segger

*

The domestic arrangements that distinguish a ménage à trois from a ménage à deux are sometimes somewhat fuzzy. And this is certainly true pertaining to the conception of the idea for Hampton Court constructed in the heart of Victoria’s Fairfield neighbourhood in 1912. As suggested by the eponymous reference to a more famous Tudor palace on the upper reaches of the Thames, this was intended as a high-end luxury apartment building.

The domestic arrangements that distinguish a ménage à trois from a ménage à deux are sometimes somewhat fuzzy. And this is certainly true pertaining to the conception of the idea for Hampton Court constructed in the heart of Victoria’s Fairfield neighbourhood in 1912. As suggested by the eponymous reference to a more famous Tudor palace on the upper reaches of the Thames, this was intended as a high-end luxury apartment building.

As recounted by Allen Specht in his very readable social architectural novella, Hampton Court: A History, a summary plot line runs something like this.

Wealthy English professional moves to British Columbia to indulge his passion for hunting and fishing. Wife decides provinciality, sporting society, and probably husband also are not for her, so decamps with children for England. Husband is befriended by sportsman buddy who is a principal in one of the largest design-build companies in Victoria. Abandoned husband moves into the capacious family home of his friend and fancies his divorced sister. Avoidance of scandal demands a creative solution. Result: creation of Hampton Court in 1913, designed and constructed by friend’s family company.

Sister, needing employment, assumes role of building manager and moves into a suite of rooms complete with servants. Admirer takes a bachelor suite across the hall. Then, as in all good Edwardian melodramas, tragedy strikes. A scant two years later, during a journey to a Cowichan fishing camp, a fatal Malahat traffic accident interrupts the cozy Hampton Court arrangement. A last will-and-testament is read. The bulk of deceased’s estate goes to the estranged widow and children in England, half of the apartment building goes to the object of the deceased’s desires. She proves a competent manager and lives well on the income for many years.

Specht opens the book by recounting this story in greater detail, weaving it into the social life of Victoria’s upper-middle-class society as the world slipped into the Great War.

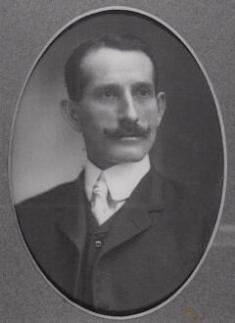

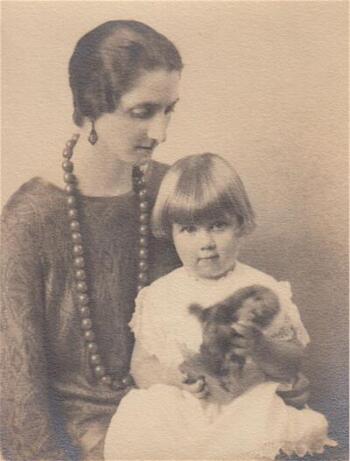

The Englishman was retired dentist Dr. Arthur Pallant. Sporting buddy was George Charles Mesher, partner of the father-and-son very successful C. Mesher and Co. The heroine in the piece was George’s sister, Annie Marie Cooke. While supervising the many construction projects of the contracting firm George also mastered, with considerable competency, the intricacies of architectural design. As contractor for many of the larger commissions of Samuel Maclure and his circle, he also developed a sympathy for the popular local Arts-and-Crafts aesthetic.

As Specht tells it, the peculiar requirements of the clients together with the talents of the architect-builder, resulted in the edifice which, on completion in 1913, was christened “Hampton Court.”

What Mesher produced was essentially an inflated Maclure hall-house. This was a formula local contemporary society architect, Samuel Maclure, had developed for his wealthy clientele to accommodate a social program of at-home entertainments. It was essentially a cross-axial arrangement of rooms on two levels pivoting from a central open hall. The ground floor often featured a massive fireplace and dramatic stairway connecting to a second-floor gallery. The hall was key to circulation through to the rooms of both floors. On the main floor sliding doors allowed rooms such as the parlour and dining to open out into the hall, according to the demands of both numbers of visitors and types of entertainment. Interiors were finished in lavish displays of native woods, the exteriors in shingle or half-timber Tudor-revival detailing in deference to prevailing late Victorian and Edwardian Arts-and-Crafts taste.

In form and massing Hampton Court was essentially a scaled-up version of Maclure’s symmetrical Georgian house-type dressed in a Tudor-revival envelope. Positioned on a street corner in a quarter block of landscaped garden, the building steps back beneath the eves of its capacious hipped roof. The three-and-half storey entrance frontage with its upper floor balconies above a central pillared entrance overlooks Beacon Hill Park. And while this manor house does not own its Romantic rural setting, it is certainly a rather clever visual conceit that borrows this element from the adjacent public park.

However, the high-point of the design, at least for its inhabitants, was the three-storey central hall (or as Specht insists “atrium”) with a feature staircase accessing two levels of galleries. The vast space was flooded with light from a central roof-top skylight. Pallant imported 10 gilt-framed oil landscapes, some depicting the countryside around his birthplace in Maidenhead, England. To this was added a large dining table and an antique grandfather clock. This assemblage lent import to achieve the desired baronial effect. In 1996 the paintings were sold at auction by Sotheby’s raising $130,000 to help cover the costs of damage caused by the collapse of the roof in the catastrophic 1996 winter snowfall. (Full disclosure: the reviewer assisted in the research and preparation of the paintings for sale).

All this is covered in chapter one. The following chapters recount the comings and goings of cooks, maids, house-keepers, furnace stokers, gardeners and delivery people who kept the numerous larders stocked, while a parade of Victoria’s social elite came-and-went against the backdrop of fading fortunes, with accompanying social slippage, that re-shaped post-war Victoria’s establishment families: widows and widowers, remittance men, clerics, senior government administrators, local celebrities, pensioned civil servants and British Colonial army officers. An archdeacon and his wife moved in, only to soon decamp for the Cathedral “palace” on his election as Bishop. Other Meshers took advantage of the opportunity. Indeed, the longest serving residents were George Mesher’s daughter and husband who over a 30-year tenancy raised two daughters there. Husband, Captain Richard Ley, after a military career, became chief inspector of the Liquor Control Board. Their daughter, Sage, received her dates in the hall: “[S]he would make the grand descent down staircase wearing a glamorous gown, with the young man waiting below to hand her a corsage.” Since the 1930s the hall has hosted a large Christmas tree to adorn it through the festive season.

Hampton Court proved a successful investment amid the post-war years of Victoria’s genteel decline in the shadow of Vancouver’s rise as new-monied entrepreneurial fortunes changed the political and economic power structures of the Province.

Tenants changed over the years but so did owners. Perhaps it was through British social connections that the Pallant family sold it in 1958 to the Duke of Westminster (or probably his international property holding company, Grosvenor Properties). And then in 1969 to George Weston’s British American Mortgage Company, who flipped it to a developer. Perhaps ironically, subject to the same forces as those of its post-First World War tenants in Victoria society, the old building had languished. But as Specht recounts, another fortuitous alignment of the stars would lead to rejuvenation. In 1976, noting possible pending demolition, the City recognized its architectural and social historic value with designation under the new B.C. Heritage Conservation Act. (Also full disclosure: this reviewer was a member of the Victoria Heritage Advisory Committee in support of the designation). Wealthy local shipping magnate Gordon Elworthy noticed the plight of a building he had become enamoured of while delivering groceries to its inhabitants as a teenager. Hampton Court was purchased, restored, retrofitted, and updated — then converted to condominiums under the new BC Strata Title act.

Since then a series of sensitive and dedicated Strata Councils have curated Hampton Court’s unique fabric, and reputation, with diligence and care.

Allen Specht, a former resident himself, also retired archivist and historian, knows his material. He wrote the biographical entry on George Mesher for Donald Luxton’s tome, Building the West. A brief list of sources and bibliography is included. Illustrations are numerous, if somewhat grainy. A series of short appendices act in place of footnotes to elucidate some points raised in the text that would otherwise impede the pace of the story.

Hampton Court: A History is a delightful romp through 10 decades of Victoria’s social history set against the evolving backdrop of a significant piece of the City’s architectural fabric.

*

Martin Segger is a museologist and art historian whose career has included academic and administrative posts at the Royal British Columbia Museum and the University of Victoria. He has taught museum studies and art history at the University of Victoria since 1973. Author of numerous publications on the architectural history of BC, including (with Douglas Franklin) the path-breaking Victoria: A Primer for Regional History in Architecture 1843-1929 (1979), he also enjoyed a long career as a gallery curator focusing on BC historic and decorative arts. A recent publication, concerning the Modernist architectural heritage of Victoria (1935-1975), Conservation Guidelines for Modernist Architecture in the Victoria Region (2020), is available in a free on-line digital version. Martin currently serves as honorary art curator for the Union Club of British Columbia and for Government House, Victoria, and he is group-co-ordinator of the UNESCO Victoria World Heritage Project. Editor’s note: Martin Segger has recently reviewed books by Liz Bryan, Michael Kluckner, Marc Treib, Daina Augaitis, Allan Collier, & Stephanie Rebick, Leslie Van Duzer, and Richard Cavell for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

9 comments on “1429 A fine Edwardian melodrama”

Great history of the area. My great-grandmother’s uncle was W.J. Macaulay who built the Pinehurst in James Bay and later the Highland on Terrace Ave above Rockland. His daughter Lily married into the Peabody line who owned the Blackball Ferry. Edwardian style can be seen all over the city.

George C Mesher the prominent architect and builder was my great grandfather and Allan Specht has done a tremendous job of researching my family history and documenting the facinating stories of those who have resided at Hampton Court.

Congratulations Allen! I am so pleased that you finally published the book. I will try and find a copy

A great synopsis of the history of a wonderfully storied building. Congrats to Allen Specht, who is a former colleague, for such a well-researched and readable book.

Wonderfully done!

I’ve often cycled past Hampton Court and wondered what sort of stories unfolded behind those windows and walls.