1428 Unfinished treaty business

To Share, Not Surrender: Indigenous and Settler Views of Treaty Making in the Colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia

by Peter Cook, Neil Vallance, John Lutz, Graham Brazier, and Hamar Foster (editors)

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2021

$37.95 / 9780774863834

Reviewed by Robin Fisher

*

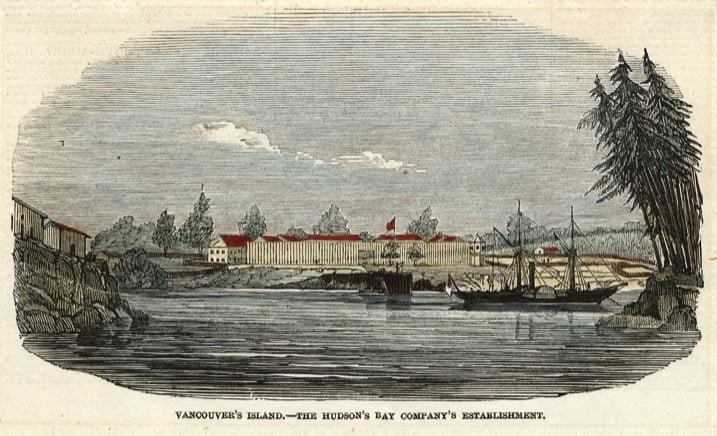

The Douglas Treaties on Vancouver Island that were “negotiated” in the early 1850s marked the one moment in colonial British Columbia when First Nations people were recognized as the owners of their land. Representing the Hudson’s Bay Company, James Douglas believed that, by signing the Treaties, First Nations had relinquished possession of their land in return for reserves that included village sites and cultivated land and the right to hunt and fish on unoccupied land as before. What the First Nations thought that they were agreeing to is entirely another matter. In any event, the treaty-making phase was brief, between 1850 and 1854, and confined to a few localities on Vancouver Island. As Governor first of Vancouver Island and then of British Columbia, Douglas did continue to treat First Nations with some fairness within the colonial context. But soon, with the arrival of more settlers to British Columbia who were then represented by new government officials, Indigenous rights were dismissed as irrelevant. Rather than an example to follow, the Douglas Treaties were ignored for one hundred years leaving the Province with the unfinished business of First Nations rights to land and resources that remains with us today.

The Douglas Treaties on Vancouver Island that were “negotiated” in the early 1850s marked the one moment in colonial British Columbia when First Nations people were recognized as the owners of their land. Representing the Hudson’s Bay Company, James Douglas believed that, by signing the Treaties, First Nations had relinquished possession of their land in return for reserves that included village sites and cultivated land and the right to hunt and fish on unoccupied land as before. What the First Nations thought that they were agreeing to is entirely another matter. In any event, the treaty-making phase was brief, between 1850 and 1854, and confined to a few localities on Vancouver Island. As Governor first of Vancouver Island and then of British Columbia, Douglas did continue to treat First Nations with some fairness within the colonial context. But soon, with the arrival of more settlers to British Columbia who were then represented by new government officials, Indigenous rights were dismissed as irrelevant. Rather than an example to follow, the Douglas Treaties were ignored for one hundred years leaving the Province with the unfinished business of First Nations rights to land and resources that remains with us today.

This volume of essays provides more information on, and new interpretations of, the Douglas Treaties. It arose out of a conference that was a genuine partnership between academics and the Lekwungen (Songhees) and other First Nations groups of the Victoria area and Vancouver Island. The three hundred people at the conference were evenly divided between First Nations and newcomers and the presentations came from both groups. I was tempted to say “both sides of the floor,” but the questions and discussion showed that there was a diversity of views among both the Indigenous and the non-Indigenous commentators. There was a moment of forthright expression seldom heard at academic conferences when a young member of the audience pronounced the scholarly papers to be “boring and irrelevant.” It was an exaggeration that contained a grain of truth. For the most interesting insights on the treaties came from the First Nations recollections of them.

The first few essays describe some of the contexts of the Douglas Treaties. Douglas’s mixed heritage background in Guyana, the First Nations milieu that he worked in as a Hudson’s Bay Company trader and his own Indigenous family were all part of the make-up of the man. Two papers describe the legal context, British and Canadian, then and since, for the Treaties. Other contexts that had a bearing on the Treaties get little or no attention. Land policy in British settler colonies, Edward Gibbon Wakefield’s ideas about systematic colonisation, mid-nineteenth century humanitarianism, treaties in other colonies, particularly New Zealand, along with the negative example of treaty making followed by warfare in Washington and Oregon, get only passing mentions at best, as if they were of little consequence.

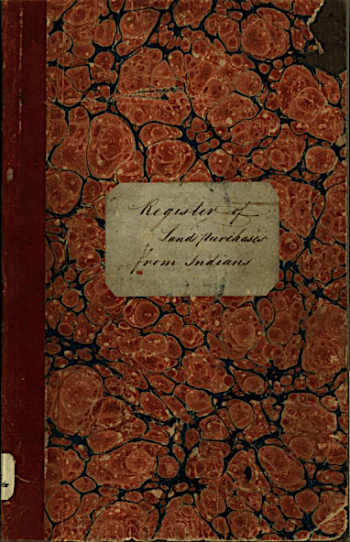

The next section of the book is a fascinating account of First Nations memories of the Treaties. First a word about how the Treaties were arrived at. Douglas or other Hudson Bay Company men would first hold a meeting with a particular group of First Nations People and outline the provisions that would be in the Treaty. Then the band leaders would sign, usually with an “X”, on an empty sheet of paper, the proverbial black cheque, to which the text of the Treaty would be added later. Treaties with Indigenous people where there was a written translation in both languages on the table at the time of signing were fraught enough. The Māori version of the Treaty of Waitangi signed in New Zealand in 1840 had significant meanings that were different from the English version. Those differences have produced years of controversy. On Vancouver Island the distinction is between a verbal description at a meeting and the written document completed afterwards. So it is not surprising that interpretations of the Treaties differ. The line of First Nations evidence is from individuals who were at the Treaty meetings, remembered what was said and then recounted it through third parties in later life. What they heard and remember is that the Treaties were presented as agreements to share resources but not to surrender ownership of the land. Hence the title of the book, To Share, Not Surrender. It has, of course, been the paper version, with its consent to surrender title, that has prevailed.

The last four essays cover the beginning and the end of the Douglas Treaty process. Graham Brazier argues that, at the time of making the Treaties, Douglas was not fully committed to the idea of recognizing First Nations title to the land and the issue was only one of his many concerns. John Lutz presents a close and detailed examination of why Douglas discontinued the treaty making approach after 1854. Using the vivid image of two rutting stags locking horns, he concludes, as others have done, that, while Vancouver Island Assembly and the Colonial Office in London both believed in principle that payment should be made to First Nations people signing treaties to surrender their land, when push came to shove, neither was actually willing to spend the money. Sarah Pike looks at how Douglas balanced settler demands for land to be made available for pre-emption with the need to protect First Nations reserves. Keith Carlson’s essay expands our understanding of Douglas’s intentions about the future of First Nations people in British Columbia. Looking closely at Douglas’s despatches to the Colonial Office in London, Carlson shows that the Governor envisaged a colonial society in which First Nations people played an integral part. The arrival of settlers seeking land meant that his vision was not realized, but that such things were even contemplated in colonial British Columbia is not a part of the public discourse about our history today.

It is easy pickings for a reviewer to raise things that are not covered in a collection of essays by many authors, like this one. At the same time, I am surprised that there is no more than the occasional mention of the White and Bob case that confirmed the legal validity of the Treaties in 1964, exactly one hundred years after Douglas left office. This absence may be a result of the focus on the Victoria area. White and Bob was not initially about title to the land but rather the right to hunt on unoccupied crown land as provided in the Treaty that had been signed in Nanaimo. As he was preparing to bring the case to court, Thomas Berger had to be convinced by Wilson Duff, the Provincial Anthropologist, that First Nations rights to the land were about ownership and not just use. The province brought unsuccessful appeals against the judgement in favour of the Douglas Treaties in White and Bob and the appeal judgements raised the matter of First Nations title even more explicitly. There is a direct line of court cases from Regina v White and Bob to Calder v British Columbia to Delgamuukw v British Columbia and Tsilhqot’in Nation v British Columbia that concluded, after fifty years of litigation, with the recognition of Aboriginal title.

But wait a minute. If, as is argued in To Share Not Surrender, the Douglas Treaties were the outcome of a haphazard process and only about sharing use and not surrendering title, where does that leave us today? Do we have to start again? Yes we do. That is why some Coast Salish groups who signed Douglas Treaties are now negotiating a new treaty under the aegis of the Te’mexw Treaty Association through British Columbia’s current treaty process. It is a much more complex negotiation than it would have been in 1850. They are at stage six of the seven-stage process.

The past is with us and history matters. Read To Share Not Surrender as a great example of how there can be different interpretations of the past. But recognise that all these interpretations are grounded in evidence, otherwise they would not be history. The Douglas Treaties are unique founding documents. It would have saved a lot of trouble if that example, or something like it, had been followed in the rest of British Columbia. That they did not become a prototype for the future is the beginning of an explanation for British Columbia’s unfinished business and why we are still negotiating such fundamental issues more than one hundred and fifty years later.

*

Robin Fisher taught and wrote history as a faculty member at Simon Fraser University before he moved into university administration and contributed to the establishment of two new universities: the University of Northern British Columbia in Prince George and Mount Royal University in Calgary. His books include Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia, 1774-1890 (UBC Press, 1977; second edition, 1992) and Duff Pattullo of British Columbia (University of Toronto Press, 1991). He has now written a biography, Wilson Duff: Coming Back — A Life, forthcoming with Harbour Publishing in May 2022. Editor’s note: Robin Fisher has reviewed books by Art Downs, Richard Boyer, William Frame & Laura Walker, and Michael Layland for The British Columbia Review, and contributed an essay in May 2021, “The Noise of Time” and the Removal of History?

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “1428 Unfinished treaty business”

An excellent review of an important, if flawed, book. Robin Fisher sets it in the context of a treaty history in BC that is only now slowly coming into public consciousness.