1425 Greta, Cassandra, Athena

ESSAY: Greta, Cassandra, Athena: Visions of Justice

by Jennifer Moss

*

Davos, Switzerland. January 25th, 2019: A small, serious, 16-year-old girl in bright purple pants perches on the edge of her chair at the widely televised World Economic Forum. She shuffles her papers for a moment, looks briefly at the camera, and begins with the simple words, “Our house is on fire.” In under 5 minutes’ time she has quietly delivered one of the most damning, incendiary speeches ever given, calling out the world leaders gathered in the audience for their lack of action on the climate issue, and warning them, “We are facing a disaster of unspoken sufferings for enormous amounts of people. And now is not the time for speaking politely” (Thunberg, No One is Too Small to Make a Difference, p. 17).

Troy, Anatolia. Late Bronze Age: A young priestess, desperate to save her people, tries in vain to warn her father, head of the Trojan army, that the wooden horse the Greeks have left perched just outside the city gates is not an acquiescent token of their defeat, but a clever trick to sneak enemy soldiers into the city. “Fools! ye know not your doom: still ye rejoice with one consent in madness, who to Troy have brought the Argive Horse where ruin lurks” (Quintus Smyrnaeus, 574-575). Everyone knows how that story turned out.

Based on the highlights of these two narratives, it’s tempting to brand Greta Thunberg, the young Swedish climate activist, as a kind of modern-day Cassandra, the cursed Trojan prophetess who foresaw the fall of her city. Parallels abound. Both women are young, visionary, and “different.” Both strive with passion to be heard, and both, all too often, are disbelieved. But applying the metaphor of Cassandra’s sad story to Thunberg’s ongoing and vital role in the high-stakes planetary survival game currently playing out across the globe, forms an incomplete picture that denies many aspects of Thunberg’s fascinating character, not to mention her achievements. Undoubtedly these women have traits in common, but if Greta Thunberg is to be compared with any of the mythological ancients, she lines up more closely with Athena, Goddess of Wisdom and War, and wielder of democratic justice. For it is Athena who first defines justice, in Aeschylus’ trilogy The Oresteia, as a concept rooted in passion, but delivered through reason, deliberation, and participation. And it is ultimately Thunberg’s unique mixture of passion, reason, and consensus-building that makes her such a formidable force for ecological justice.

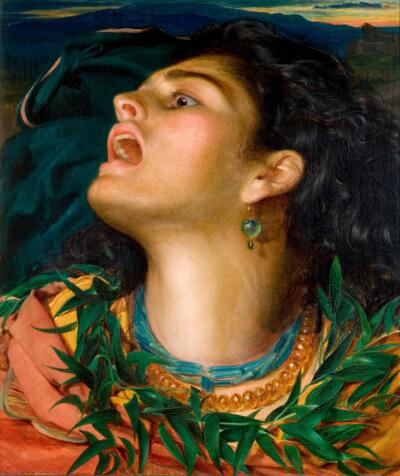

Seeing the Future: To better understand what makes Cassandra and Thunberg different, it is important to first explore where they overlap. Certainly, the two young women share the common trait of focusing intensely on the future. According to the Cassandra myth as outlined in Aeschylus’s Agamemnon, part of the Oresteia Trilogy, Cassandra was a virgin priestess given the gift of prophecy by the powerful sun-God, Apollo. At first, she promised to marry him, but soon after receiving her magical future-vision abilities, she went back on her word. Perhaps she foresaw what life married to a fickle and all-powerful god would be like. So, she refused to kiss him. The angry Apollo could not take back a divine gift, so he “added” to it instead. Spitting into her mouth, he uttered the curse that nobody would ever believe her prophecies. This curse has made Cassandra an object of fascination down through the ages. Women, who have fought patriarchy ever since Apollo first took over management at the temple of the She-Serpent, tend to relate personally to her story of being unilaterally dismissed. Cassandra’s story makes every woman who reads it flinch, not in fear or horror, but in recognition.[1]

So far as anyone knows, Greta Thunberg has never had a brush with an arrogant curse-casting God. Rather, her visionary outlook emanates from her sincere concern, even obsession, over the future of this planet. While not a cloistered virgin priestess, she does stand somewhat apart from regular society in the sense that she has Asperger’s Syndrome. Having this kind of high-functioning Autism means that she has difficulty with social interaction and sensory reception. She tends to focus on details, and dive deep into learning about particular subjects. By her own admission, she sees things as either black, or white. In No One is Too Small to Make a Difference, she writes:

They keep saying that climate change is an existential threat and the most important issue of all. And yet they just carry on like before. If the emissions have to stop, then we must stop the emissions. To me, that is black or white. There is no grey area when it comes to survival (Thunberg, p. 6).

We see here how Thunberg, strongly driven by logic, is essentially incapable of denial. When the world’s leading scientists use logic and evidence to describe the catastrophic potential of climate change, she takes them quite literally. She sees planetary destruction as the direct consequence of our current actions, and advocates that the only way to avoid it is to change the way we operate. She has devoted several years of her young life to “prophesying” the doom we will all face if we don’t mend our ways, simply because she believes the science, and has accepted it as the truth.

Dismissed and Abused: Besides their shared obsession with the future, and the truth, the other place where Cassandra and Thunberg’s personalities overlap is through their common experience of character assassination. There are many versions of the Cassandra myth, but in each of them, she is openly reviled for her critique of King Priam (her father) and his tactics, and her perceived disloyalty to the cause of Troy. In Christa Wolf’s Cassandra: A Novel and Four Essays, Wolf’s imagined Cassandra laments how even her father has come to disdain her for her dire predictions. “It was I, of all his children my father believed, who betrayed our city and betrayed him” (Wolf, p 14). In Wolf’s contemporary reimagining of the myth, Cassandra’s credibility is further undermined by Troy’s early successes in the war, which seem to disprove her visions. “The progress of the war seemed not to bear me out. Troy was holding its ground […] for some time it was not under threat” (p. 106). Her predictions about the fall of Troy are therefore roundly ignored. In Homer’s Iliad, “Priam’s loveliest daughter” (Homer, Iliad, transl. Eagles, 13:424) is disgraced and bartered off, first as a war bride to an ally of her father’s, and finally as a sex slave to the conquering Greek king, Agamemnon. In spite of all this, Cassandra remains loyal to Troy until, according to Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, she is ultimately killed for this allegiance. Agamemnon’s wife Clytemnestra, jealous that her husband has returned from Troy with Cassandra in tow, murders both of them in cold blood — but not before Cassandra predicts her own demise.

Oh, oh! Agony, agony!

Again the awful pains of prophecy

Are on me, maddening as they fall….

Ye see them there … beating against the wall?”

Poured out like water among them. Weep for me….

Ah! What is this place? Why must I come with thee….

To die, only to die? (Aeschylus, 1130-1149).

In every version of the story, her prophecies make her unpopular, and set her apart. Yet to the bitter end, Cassandra passionately insists on the truth of her visions. In Wolf’s version, even though she understands her death is imminent, Cassandra vows, “I will continue a witness even if there is no longer one single human being left to demand my testimony” (Wolf, p. 22).

Greta Thunberg also knows a thing or two about being doubted, set apart and reviled. Like the Trojans who doubted Cassandra because Troy appeared to be winning, there are those who still doubt Thunberg’s statements about climate change, citing circumstantial evidence as “proof” that climate change isn’t real. For instance, the former president of the United States, Donald J. Trump issued dozens of tweets suggesting that a spate of cold weather disproves climate change. He also took Thunberg on directly via Twitter, painting her as a hysterical child with an “anger management problem.”[2] The personal attacks did not stop there. The fact that Thunberg has Asperger’s Syndrome is often used as grounds for dismissal by her critics. As Jennifer O’Connell notes in The Irish Times in 2019:

The Australian conservative climate change denier Andrew Bolt called her “deeply disturbed” and “freakishly influential” (the use of “freakish”, we can assume, was not incidental.) […] Brendan O’Neill of Spiked called her a “millenarian weirdo” (nope, still not incidental) in a piece that referred nastily to her “monotone voice” and “the look of apocalyptic dread in her eyes” (O’Connell, Irish Times, September 2019, “Why is Greta Thunberg so Triggering for Certain Men?”).

Such vitriol might slow down another teenage girl, sending her rushing to the mirror to critique her fragile self-image. In Thunberg’s case however, while she no doubt feels these barbs, she deals with her critics calmly and directly.

I’ve seen many rumours circulating about me and enormous amounts of hate. This is no surprise to me. I know that since most people are not aware of the full meaning of the climate crisis (which is understandable since it has never been treated as a crisis), a school strike for the climate would seem very strange to people in general (Thunberg, p. 23).

At the UN Climate Change Conference in Poland, 2018, she called out the adults who dismissed her as a mere child, or tried to soften the urgency of her environmental message. Like Cassandra, she refused to back down in the face of those who would deny the truth. “You are not mature enough to tell it like it is,” she said, “Even that burden you leave to your children. But I don’t care about being popular. I care about climate justice and the living planet” (Thunberg, p. 13).

A Question of Voice: Where Thunberg’s story finally begins to peel away from the Cassandra myth is in both the timbre, and the source of her predictions. Cassandra’s voice signals hysteria, a heightened form of passion, while Thunberg’s embodies logic and reason. As a priestess, Cassandra channels the voice of Apollo. While Apollo is the God of Reason, he speaks through Cassandra, rather than to her. He effectively takes over her internal airwaves like some kind of guerrilla signal, which has a disorienting effect on Cassandra herself. Under Apollo’s curse, Cassandra functions like an ancient Greek version of the possessed Victorian parlour medium, or an overzealous southern preacher, speaking in tongues. Christa Wolf’s Cassandra explains, “We have no name for what spoke out of me. I was its mouth and not of my own free will” (Wolf, p106). There is a note of elevated hysteria to Cassandra’s predictions. In Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, she screams aloud to the chorus, “I lose my screams, they find me again! / The dread work of prophecy buckles me / down to its BAM BAM BAM – / Do you see…?” (Aiskhylos, Agamemnon, 907-910, translated by Carson, p. 54). But the people do not see. If the way the Greek chorus in this version of the story responds to her predictions is any indication, they totally misunderstand her. After Cassandra delivers a symbolically complicated and gory prophecy involving dripping entrails and dead children, predicting the murder of Agamemnon himself, the chorus still claims to be mystified, saying, “I get that one, it makes me cold with fear, after that, you were unclear” (Aiskhylos, p. 56, 933-934). Cassandra’s curse is that she won’t be believed, no matter how truthfully she speaks. But as this passage indicates, the curse may run even deeper than that. While her knowledge of future events is clear, her God-infused communication style is often opaque. She regularly spouts bloody symbols and arcane visions. Effectively, Cassandra, as a mere mouthpiece for Apollo, is cursed to be unable to express herself in a way that others can fully understand. Her dying wish is therefore quite naturally to sing her own dirge — thus freeing her voice from its captivity. She makes one final utterance, one last prophecy for humankind. “I’m just a killed slave, easy fistful of death. But you, o humans, o human things—when a man is happy, a shadow could overturn it. When life goes wrong, a wet sponge erases the whole picture. You, you, I pity” (Aiskhylos, p. 60, 993-1007). In this speech we see the crux of Cassandra’s problem: the gift of foresight has allowed her to see clearly the extreme state of vulnerability that humans live under. And this vision pains her. It literally makes her seem crazy, so much so that she lacks the clarity of expression that would allow others to easily understand her meaning.

Nothing New Under the Sun: Cassandra’s is a dilemma many women, in particular, can relate to, given how often women’s voices have been subjugated and sidelined throughout history. Women, frequently dismissed as “worriers,” live daily with Cassandra’s burden. In Cassandra Speaks, a book that re-examines foundational myths from a feminist perspective, Elizabeth Lesser notes that, “The American Psychological Association dropped the term ‘female hysteria’ in 1950. It was replaced with the more Freudian term ‘Hysterical neurosis’ which was not dropped from the Diagnostic Manual for Mental Health until 1980.” Even today, the theory of a pathological “uterine fury” follows us, demeans us, and causes us to doubt and silence ourselves (Lesser, Cassandra Speaks, p. 55).

Women are diagnosed with anxiety disorders at nearly twice the rate of men, according to a 2016 study in the journal Brain and Behavior (Remes, et al). This happens mainly from puberty to age 50. Our “worrying” is in part due to our historical vulnerability to rape, or rather, to the patriarchal tendency of some men to rape. Many women have, as a result of this age-old pattern, developed the ability to foresee potential negative consequences down every dark alley. Our concerns are borne from experience, and a desire to keep ourselves and our loved ones safe. Yet women often find themselves ridiculed or dismissed for taking an overly anxious, morbid, though arguably informed view of the world. That said, Cassandra’s predicament resonates for anyone who has attempted to make a rational argument about a subject that matters deeply to them, but found themselves overcome by emotions or fears, found themselves choking on their own words, crying or hysterical, thereby effectively undermining their own message. It is an unenviable position.

Our Very Own Complex: The “Cassandra Complex” is a highly gendered term first coined by French Philosopher Gaston Bachelard in 1949, describing a psychological phenomenon in which an individual’s accurate prediction of a crisis is ignored or dismissed. In her well-known book The Cassandra Complex: Living with Disbelief — A Modern Perspective on Hysteria (1988), psychologist Laurie Layton Shapira explores underlying social causes of “The Cassandra Complex.” Shapira lays out the connection between ancient Cassandra the prophetess, subsequent oracles, later clairvoyant mediums, fainting couch Victorian hysterics, and contemporary women with mental health problems such as narcissistic personality disorder. She talks about the “hysterical woman” as a woman who is actually oppressed by the poorly articulated but nevertheless present and real troubles of her time, a woman who is plagued by the dark side of the subterranean collective unconscious. This type of hyper-sensitive woman is so incapacitated by those problems (and her inability to express them or be heard) that she becomes “hysterical.” She functions as a “canary in the coal mine” for whatever ails society at the time. Using this reasoning, the tight corsets worn by Victorian women were merely the physical manifestations of that society’s spiritually crushing, patriarchal, uptight insistence on sexual repression, female domesticity, and its generalized fear of the body. Repressed sexuality and boredom, rather than restrictive undergarments, were arguably the real reasons women constantly fainted on couches during that era.

Subterranean Blues: This line of thinking raises the question, what are the underlying, poorly articulated troubles of our time? And what neuroses are they provoking? If you ask anyone from Greta Thunberg’s generation, they will not hesitate to tell you: They fear extinction. They fear environmental collapse. They fear a planet that will no longer sustain life. They fear. So much so, that many of them are foregoing having children. According to a recent article in The Atlantic, “Miley Cyrus vowed not to have a baby on a “piece-of-shit planet.” Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez mused in an Instagram video about whether it’s still okay to have children,” (Green, The Atlantic, “A World Without Children” Sept 20 2021). In a recent survey by Yale-NUS College in Singapore published in the Journal of Climatic Change conducted with 600 people aged 27 to 45, 96.5 percent said they were “very” or “extremely” concerned about the wellbeing of their potential future children in a climate-changed world. One 27-year-old woman said “I feel like I can’t in good conscience bring a child into this world and force them to try and survive what may be apocalyptic conditions” (Schneider-Mayerson, et al, “Eco-reproductive concerns in the age of climate change” Climatic Change, 163, 1007-1023).

Critics dismiss this viewpoint as hysterical, or extreme. Older people, who have lived through other forms of adversity, tend to write this off as the hyperbole of the younger generation. But young people, people like Greta Thunberg, feel this heightened level of discourse is warranted. Remember, they believe in science. They watch the numbers, and take the long view because, quite simply, they will live longer than their parents and grandparents. As Thunberg said in her 2019 speech at the United Nations Headquarters in New York:

The popular idea of cutting our emissions in half in 10 years only gives us a 50% chance of staying below 1.5 degrees [Celsius], and the risk of setting off irreversible chain reactions beyond human control. Fifty percent may be acceptable to you. But those numbers do not include tipping points, most feedback loops, additional warming hidden by toxic air pollution or the aspects of equity and climate justice. They also rely on my generation sucking hundreds of billions of tons of your CO2 out of the air with technologies that barely exist. So a 50% risk is simply not acceptable to us — we who have to live with the consequences (Thunberg, p. 97).

Here we see how Thunberg defends her vision about the impact of our current actions on the future, using logic and reason. She feels passionately, and has, on occasion, even seemed close to crying in delivering her words.[3] But the words themselves are rooted in facts. Empirical evidence. Detail. In this way, she diverges from the god-channelling, hysteria-tinted, parlour medium-like prophecies of Cassandra.

No Mere Mouthpiece: Unlike Cassandra, Thunberg is no mere mouthpiece, though she has certainly been accused of being one. Her critics, perhaps unable to fathom that such a young woman could hold such well-informed and strategically-timed views, have postulated that she must be governed by political forces behind the scenes. For instance, Thunberg was called a “puppet of Western politicians” on Chinese social media outlet Sina Weibo, after she publicly targeted China on its annual emissions (Global Times, May 21, 2021). She handles such critiques as neatly as she folds her single sheet of paper when giving one of her globally televised speeches. In 2019, she posted on Facebook:

Many people love to spread rumours that I have ‘people behind me’ or that I’m being ‘paid’ or ‘used’ But there is no-one behind me except for myself. Even my parents were as far from climate activists as is possible before I made them aware of the situation. I am not part of any organization. I sometimes supported and cooperated with several NGOs that work with climate and the environment, but I am absolutely independent and I only represent myself. And I do what I do completely for free (Thunberg, p. 22).

In her efficient, unemotional response to critics and her determined refusal to take her eyes off the larger issues, Thunberg neatly sidesteps the Cassandra Complex, and displays none of the self-defeating neurosis, or hysteria can sometimes occur when you are disbelieved by the people around you. While she often speaks passionately, Thunberg always speaks with great clarity, in a way that is difficult to ignore or misconstrue. At her UN Headquarters speech, for instance, she pleads with the adults in the room, while on the verge of tears, “This is all wrong. I should not be up here. I should be in school, on the other side of the ocean. Yet you all come to us young people for hope. How dare you?” From these words, and from her demeanour when she delivered them, we can deduce that Thunberg feels deeply about the issue of climate warming. Yes, it upsets her. Safe to say it probably infuriates her. But it does not hold her back from laying out her argument, and in this speech, we see a remarkable young woman channelling her fury into cold, hard facts.

Meanwhile, many young people are, sadly, so demoralized by their climate anxiety, they have dropped out of the environmental debate altogether. Others feel so desperate they have chained themselves to old growth trees or gone on hunger strikes. Some are so angry, even vengeful, that they have joined eco-terrorist groups to plant spikes in trees to stop logging. Thunberg, on the other hand, believes in applying reason — the common currency of “adult” discourse — to the situation. She calls upon us all to join her movement, to act, before it is too late. She puts the blame squarely on the shoulders of the world’s adults, refusing to let us squirm out of our responsibilities. In this way, Greta Thunberg begins to resemble not Cassandra so much, but Athena, Goddess of Wisdom and War, and instigator of deliberative justice, the foundation of Athenian democracy. Like Athena, Thunberg believes power lies squarely with the people, and that we must never forget that solutions are within our grasp. In Davos 2019, she declared “Homo Sapiens have not yet failed. Yes, we are failing, but there is still time to turn everything around. We can still fix this, we still have everything in our own hands” (Thunberg, p 18).

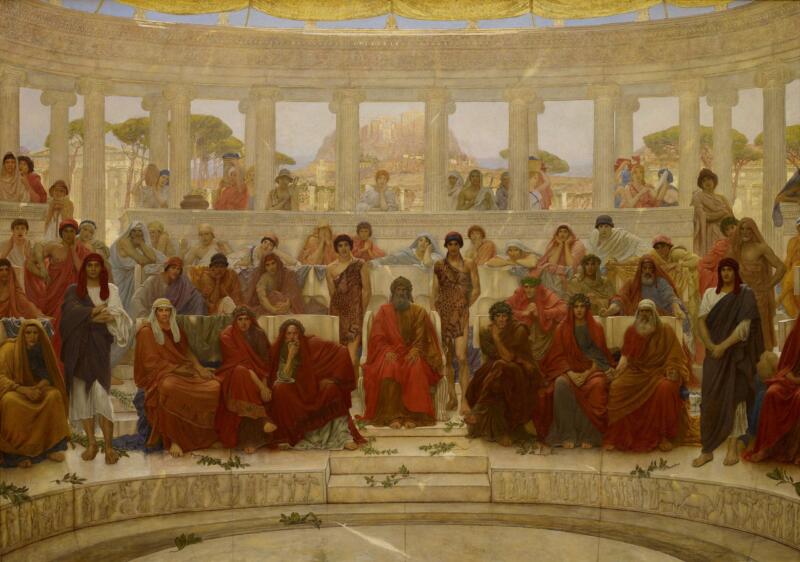

Fury vs Consensus: In the latter half of the trilogy The Oresteia, after Cassandra’s screams have died out, Aeschylus’s exploration of vision, belief, retribution and justice continues. In the story, Athena plays a key role. Her actions illustrate the reason she is associated with deliberative justice, that is, justice based on mutually-arrived-at understanding rather than vengeance. It has to do with the role she plays in the trial of Orestes in the third play, The Eumenides. By his own admission, Orestes has murdered his mother, Clytemnestra. Recall that Clytemnestra herself is also a murderer, having killed her own husband Agamemnon, along with Cassandra. Agamemnon, in turn, was a king who had coldly sacrificed his and Clytemnestra’s teenage daughter in the public square before heading off to war in Troy, to appease the gods and raise the winds for a safe journey. He argued that the Gods made him do it, but it’s little wonder his wife was mad at him. In old-school Greek mythological logic, Agamemnon had been acting on the orders of the Gods, so his murderous actions are considered semi-sanctioned. But Clytemnestra, by killing her husband in unbridled revenge, had clearly upset the natural (or Apollonian) order. Apollo therefore sends a message through an oracle to her son, Orestes, that he should restore balance by killing his mother. Orestes does so, but eventually must stand trial for his actions. The murder trial of Orestes is essentially the culmination of several generations of finger-pointing and revenge killing in the House of Atreus. Not unlike Thunberg making her motivating climate speeches against a backdrop of forest fires and floods, Athena arrives at the eleventh hour, when this prominent family is knee deep in blood and transgression, to help sort it out.

The Greek’s ancient law of retaliation was enforced by old female deities known as The Furies. According to Aeschylus, Destiny gave them this role at the dawn of time: “you’ll give me blood for blood, you must! … Wither you alive, drag you down and there you pay, agony for mother-killing agony!” (Aeschylus, The Eumenides, Griffith et al, lines 262, 265). The Furies take issue with Orestes’ tendency towards matricide, despite the fact that he reportedly has Apollo on his side. They show up at Orestes’ trial to exact vengeance and uphold the ancient cycle of violence begetting more violence — blood for blood — because they believe that the law of retaliation is absolute (Anderson, Justice in the Oresteia).

Apollo is counsel for the defence, arguing that Orestes has spent years wandering the earth, atoning for killing his mother, and is now a changed man. He also points out that it was he who gave Orestes the idea to kill Clytemnestra in the first place. In broad strokes, Apollo stands for reason, rationality, the tidy patriarchal world order. The Furies represent the feminine power, the underworld, and the old ways. In The Eumenides, they sing a wild chant, calling upon instinct, revenge, and the triumph of righteous rage, or hysteria, over intellect.

Over the beast doomed to the fire

this is the chant, scatter of wits,

frenzy and fear, hurting the heart,

song of the Furies

binding brain and blighting blood

in its stringless melody (Aeschylus, The Eumenides, lines 328-333).

Enter Athena, Goddess of War, but more pertinently here, of Wisdom. She acts as judge at the trial, listening to both sides, making her views occasionally known, but largely hanging back so that others may weigh the facts of the case. “…by all rights, not even I should decide a case of murder-murder whets passions” (lines 486-487). The central question at the trial is whether this new form of persuasive argument leading to consensus will be able to bridge the gap between Apollo’s coldly reasoned interpretation of Zeus’ almighty will, and the ancient vengeful laws of the Furies. These are complex moral questions that Athena asks a mortal jury (The Chorus) to consider. She realizes that if she were to simply declare a winner without soliciting consensus, the curse on the House of Atreus (Orestes’ family) will never end. Athena is not, in this instance, vengeful, spiteful, or destructive. She invokes a higher wisdom and asks the jury to apply a kind of justice that takes the specifics of the case into account. During the trial, she admonishes the chorus, “You wish to be called righteous rather than act right. […] I say, wrong must not win by technicalities” (Aeschylus, The Eumenides, line 430). In how she addresses the jury, and ultimately (after consideration) sides with Orestes, Athena presents a logical, connected, and bold version of justice. In his article “Athena’s Way: Jurisprudence of The Oresteia,” legal scholar Desmond Manderson notes, “Athena demonstrates a vision of judgment as a participatory and transformative process. Above all, she insists on the essential role of public legal argument and public accountability” (Manderson, Law, Culture, and The Humanities, 2019, Vol. 15, p. 253).

Athena’s Way: Arguably, we are to Thunberg what the Greek chorus is to Cassandra, and what the jury is to Athena in The Oresteia. We listen to her speeches. We weigh the words coming out of her mouth. We decide where we stand on the issues she raises. We are the ones who must act, or not act, upon her recommendations. But Thunberg’s words are not cloaked in symbolism as Cassandra’s often were. Therefore, while some of us may disagree with her, we cannot pretend to misunderstand her. Nor are Thunberg’s words composed of pure rage in the absence of evidence or circumstantial deliberation like the Song of the Furies. Therefore, we are forced to acknowledge the logic of the factual information that underpins her passionate argument. We may stomp our feet, fury-like, and reject her, but through her prolific speech-making and clear-headed presentation, through her networking and advocacy, she stands at the helm of the proceedings, like Athena in the trial of Orestes, to ensure that we must at least hear the evidence first.

At the end of the trial of Orestes, after hearing everyone’s testimony, ultimately Athena upholds Apollo’s argument that Orestes was justified in killing his mother. She is able to acquiesce to the idea that he has suffered enough, seeing as he has already wandered the land for many years atoning for this violent and misguided action. Interestingly however, she makes a point of acknowledging the continued role of the Furies. Instead of banishing their sensibilities of passion and vengeance to the underworld altogether, she uses the power of her persuasive words — and the facts of the case — to convince them to reinvent themselves into the Eumenides, or “well-meaning, soothed goddesses” (“Erinyes,” Encyclopedia Mythica, 17 March 1997). They become, effectively, goddesses who were angry, but are now soothed, because they have seen real justice done. This palimpsest of new ways overlapping but not obscuring the old consummates the sense of balance, or “all’s well that ends well” in the play. We feel satisfied that Orestes’ crime was called out, addressed, and eventually ruled on — with appropriate actions taken, given all the facts and persuasive arguments. The play introduces not blind obedience to the law, but rather an exploration of the way the law can be interpreted and enacted. Fury, vengeance — the old “blood for blood” principle — is sublimated but not altogether discarded. As Manderson puts it, “A logic of equivalence lies at the very heart of the law, then and now” (Manderson, p. 261). This is “Athena’s way.”

This is also Thunberg’s way. Looking again at Greta Thunberg through the prism of Greek Mythology’s story of Cassandra, and foundational figures of western justice like Apollo, the Furies, and Athena, it would be a mistake to present her as either a cold, purely rational Olympian, or a hysteria-spouting, rage-wielding vessel for arcane visions. Either extreme interpretation makes her too easy to dismiss. True, she has Asperger’s Syndrome, which allows her to present herself especially logically in the face of adversity. However, as her tearful and passionate speech at the UN Headquarters in 2019 demonstrates, she also feels deeply, and is strongly motivated by a fury-like sense of outrage at the adults of the world who have created the mess that she and her peers must inherit. In all her public discourse, she pulls in facts about climate change, and attempts to use them to build momentum for the cause, in order to see real justice done for the planet, and for her generation.

It’s also a mistake to place either Thunberg or Athena on a binary scale of “feminine” vs. “masculine” justice. Neither advocates reason without passion, nor passion without reason. Instead, they demand a kind of justice that fuses both forces, simultaneously. As Manderson notes:

Ultimately, in the figure of Athena, Aeschylus undoes any simple gender binaries. For the judgment inaugurating a new legal order, a new process and system, is founded on Athena’s act of lawless freedom – the application of supposedly feminine subjectivity tempering the objectivity of the existing law (Manderson, p. 65).

Here, Manderson refers to the way Athena employs dialogue, in the form of both passionate persuasion and logical argument to challenge the status quo — which is blind acceptance of the ancient “blood for blood” law.

Change is Gonna Come: Like Athena presiding over the trial of Orestes, Thunberg seems to know that — while the laws of nature are as old as the Furies, and the earth demands the blood of those who disrespect it — there will be no true action against climate change, no true environmental justice, without consensus. In “Athena’s Way,” Manderson reinforces this sentiment by citing Blaise Pascal, who said, “justice without force is helpless; but force without justice is tyrannical’’ (Manderson, p. 35). Thunberg’s relentless campaigning, her track record of school strikes and speeches, attest to her understanding of this reality. She recognizes that fury alone is not enough. Dire predictions without action do nothing. Mere lip service to justice will not advance us, but neither will violence. Just as Athena ushered in a new era of informed and participatory justice by asking the Chorus to reconsider their blind acceptance of the old ways, Thunberg is ushering in a new way of thinking about the future, and she is not doing it alone. She, and the millions of school-aged children and adults who now support her, beg us to reconsider our use of fossil fuels, to embrace the circular economy, and to get serious about rewilding nature. Thunberg has spurred-on a dramatic change in how young people see themselves and their role in society. For one who undoubtedly has flashes of the Goddess about her, Thunberg is all business. She’s blunt, and matter-of-fact about her mission. “We are changing the world. So that when we are older we will be able to say we did everything we could. And we will never stop doing that. We will never stop fighting for the planet and our future” (Thunberg, p. 105). Truer words were never spoken.

*

Jennifer Moss is a Master’s student in the Graduate Liberal Studies program at Simon Fraser University. In her other life, she’s a new media producer, runs a podcasting company, and teaches Creative Writing for New Media and Podcasting at the University of British Columbia. Her writing focuses on the migration of ideas and stories across geography and spaces. She is also an audio storyteller with a long history of writing and producing for radio, and she’s the Creative Director at Vancouver’s JAR Audio. She is most interested in cross-genre and cross-departmental collaboration, and in continually exploring how emerging technologies open new doorways for writers. Editor’s note: Jennifer Moss has previously written two short stories, Friendiversary and A Modest Silence, and a Pandemic Letters poem, Sit Down, Death, for The British Columbia Review.

*

Endnotes:

[1] According to the Suda, a 10th century Byzantine encyclopedia, Apollo’s main temple at Delphi took its name from the Delphyne, the she-serpent (drakaina) who lived there and was killed by the god Apollo.

[2] After Thunberg was voted Time Magazine’s Person of the Year in 2019, Trump tweeted, “Greta must work on her anger management problem then go to a good old-fashioned movie with a friend. Chill Greta, Chill.”

[3] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N94eP2jKQWw

*

Works Cited:

Aeschylus. The Agamemnon of Aeschylus; Translated by Murray Gilbert, New York, London [Etc.] Oxford University Press, 1 January, 1970

Aiskhylos, Sophocles, and Euripides. An Oresteia: Agamemnon by Aiskhylos; Elektra by Sophokles; Orestes by Euripides. Translated by Anne Carson: Faber and Faber, 2013.

William Anderson, “Justice in The Oresteia,” in SchoolWorkHelper, 2019.

Griffith, M., Glenn W., Lattimore, R. Greek Tragedies 3: Aeschylus’ The Eumenides; Sophocles’ Philoctetes, Oedipus at Colonus, Euripides: The Bacchae, Alcestis, University of Chicago Press, 2013

Aeschylus, The Oresteia, Translated by Robert Fagles, William B. Stanford. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1979.

Cheung, Helier. “What Does Trump Actually Believe on Climate Change?” BBC News, BBC, 23 Jan. 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-51213003.

“Erinyes.” Encyclopedia Mythica. Encyclopedia Mythica, 17 Mar. 1997. Web. 23 Nov. 2021.

Times, Global. “Thunberg Mocked as ‘Double-Standard Environmentalist,’ ‘Puppet of Western Politicians’ for Targeting China on Annual Emissions.” Global Times, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202105/1222988.shtml.

Green, Emma. “A World without Children.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 18 Oct. 2021 https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2021/09/millennials-babies-climate-change/620032/.

Homer, The Iliad, Transl. Robert Eagles, Viking Penguin (Penguin Classics), 1990.

Layton Shapira, Laurie, The Cassandra Complex: Living with Disbelief – A Modern Perspective on Hysteria, Inner City Books, 1988.

Lesser, Elizabeth, Cassandra Speaks, Harper Wave, 2020.

Manderson, Desmond. “Athena’s Way: The Jurisprudence of The Oresteia” Law, Culture, and Humanities, Vol 15, 2019.

Matthews, Dylan. “Donald Trump Has Tweeted Climate Change Skepticism 115 Times. Here’s All of It.” Vox, 1 June 2017, https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/6/1/15726472/trump-tweets-global-warming-paris-climate-agreement.

O’Connell, Jennifer, “Why Is Greta Thunberg so Triggering for Certain Men?” Irish Times, Sept 7, 2019, https://staging.quantumrun.com/Signals/why-greta-thunberg-so-triggering-certain-men.

Quintus Smyrnaeus. The Fall of Troy. Translated by Way. A. S., Loeb Classical Library Volume 19. London: William Heinemann, 1913

https://www.theoi.com/Text/QuintusSmyrnaeus1.html

Remes, O., Brayne, C., van der Linde, R., Lafortune, L.. “A systematic review of reviews on the prevalence of anxiety disorders in adult populations,” Brain and Behavior, 2016.

Schneider-Mayerson, M., Leong, K.L. “Eco-reproductive concerns in the age of climate change,” Climatic Change 163, 1007–1023 (2020).

Thunberg, Greta, No One is Too Small to Make a Difference, Penguin Books, 2019.

Wolfe, Christa. Cassandra: A Novel and Four Essays, Farrar, Strauss, Giroux, 1984.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and writers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1425 Greta, Cassandra, Athena”

Nice piece. Glad to see it here on Ormsby!

T